Chandralekha, born Chandralekha Prabhudas Patel on December 6, 1928, into a Gujarati family in Wada, Maharashtra, was an Indian dancer, choreographer and activist. She was born into a house of contrasting ideals, to an agnostic father and a devout hindu mother. The agnostic and religious influences in her upbringing would later emerge distinctively in her work spanning six decades.

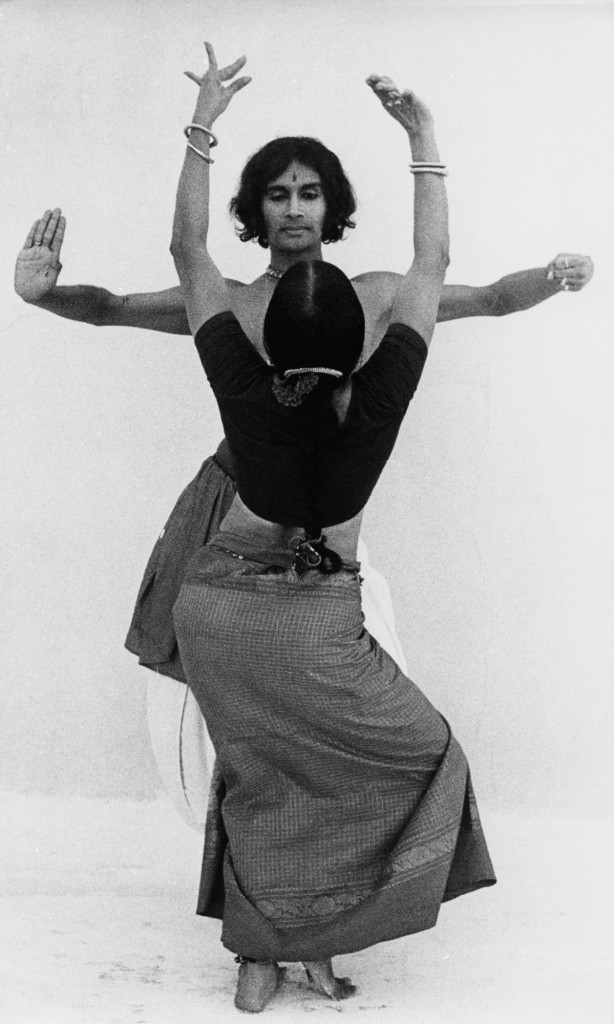

Acclaimed for her choreographic work, Chandralekha is known for introducing elements of yoga and kalaripayattu, a martial art originating in Kerala, to dance, and what came after, was a distinct method. She incorporated movements and techniques from yoga and kalari, creating an imagery full of abstractions aesthetically mirroring sculptural postures and athletic vigor.

Early years of the Bharatanatyam debutante

At 17, as a young student of law, Chandralekha gave up her studies to pursue Bharatanatyam, a classical dance form originating in Tamil Nadu. She moved to Madras, and would remain in Madras for the rest of her life. In Madras, Chandralekha started taking intensive Bharatanatyam lessons from Guru Elappa Pillai. She discarded her surname and answered to her given name alone. Soon, she was known as Chandra among her peers.

Chandralekha has credited a singular moment in her memory to have shaped her response and attitude towards dance. It was in the year 1952, during her arangetram, the traditional initiation into the world of performing Bharatanatyam, when she experienced the conflict between art and life. At the time, the region suffered a severe drought but in her dance, she was depicting the joyous imagery of the people of Mathura bathing in the river Yamuna to greet Krishna. Her work ever since, has been an attempt at the resolution of the conflict between art and life, to attune to the realities of life and society.

At a time (1950s) when Bharatanatyam was undergoing hegemonic change, subjecting both the art and the artist to the wills and morals of Brahminical and nationalist ideals, of “reform” and resurrection, Chandralekha distinguished herself and her art, albeit, disapprovingly, to not cater to the approvals of the popular audience. She established her primacy through non-conformity to what was sold as palatable dance. While she had no reference points, it was the life and work of the notable dancer T. Balasaraswati that profoundly influenced Chandralekha. In 1960, while practicing dance full time, she wrote as well. She published the lesser known collection of prose titled Rainbows on the Roadside: Montages of Madras. This collection followed her stream of consciousness centering her experience of Madras, its air, soil and water, through her senses and her body.

Chandralekha’s explorations of the body

Chandralekha found no intrigue in imitating the gods, a theme popular in Bharatanatyam. She was more concerned with the human body, the human condition, and the human bondage. She set on a course to liberate the body and explore what she called the geometry and the limitlessness of the dancer. By doing so, her dance imitated life itself. In pursuit of this liberation, she dispensed with the ornamentation in dance.

Chandralekha found no intrigue in imitating the gods, a theme popular in Bharatanatyam. She was more concerned with the human body, the human condition, and the human bondage.

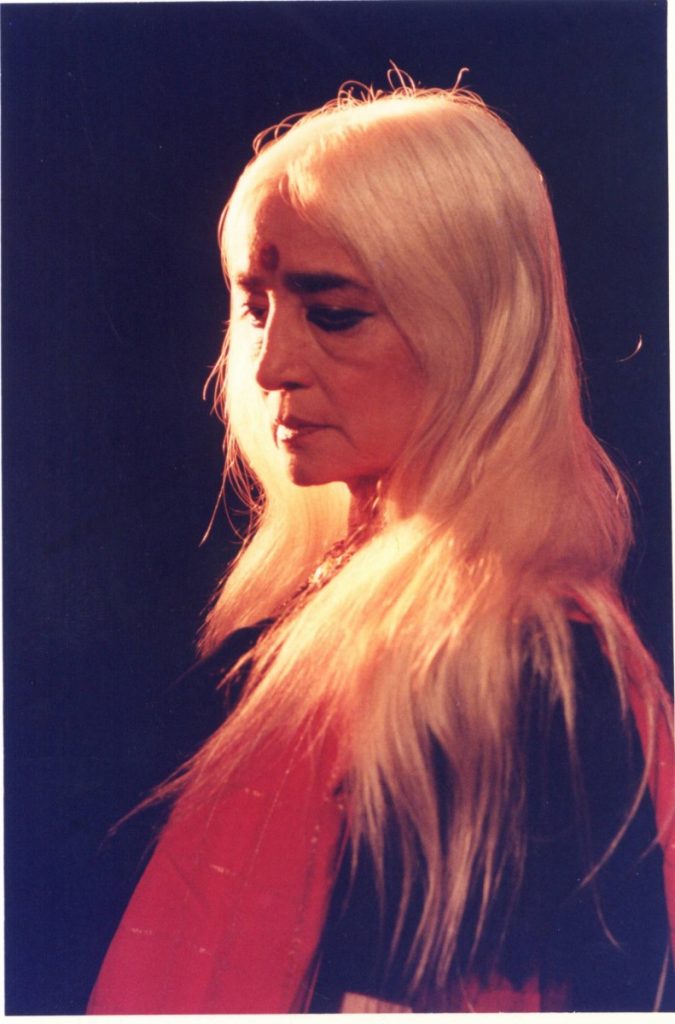

Chanralekha’s choreographic works, albeit complex in abstraction, were notable for being tremendously minimal. Bharatanatyam dancers when performing in full regalia would don heavy ornamentation and accentuated make-up to complement the expressions and movements, creating a beautiful picture for the audience. However, Chandralekha found this ornamentation to be the very disruptive force coming between the artist and their body and invariably, the artist and the audience. A Chandralekha dancer thus had the freedom of the body from ornamentation, akin to everyday practice or rehearsals. This was her conceptualisation and she incorporated it rigorously in her dance as in her life. Known for her silver hair, she refused to dye it black despite being an active performer at the time, something that her contemporaries would never dare to do.

She did not seek to pacify the unknown, but rather adapted it to form a part of the experience of her work, the human experience. At a time when, including to date, the ability to serve as a medium between the common and the divine, or reverence to the sacred continues to remain the sine qua non of life in classical dance, Chandralekha rooted her art in the human experience and she was clear that this human experience did not involve religion as a definable area. She liberated the form from any ritual sense and filled it with intuition. She did not engage with dance to draw a distinction between the sacred and the profane. Instead, her work, which she often defined as “celebrations of the human body” dealt with movements imitating the intangible thus demanding passion and power from her dancers.

Chandralekha’s subversions received backlash for belonging to a “vulgar” realm of art. Critics and the popular audience designated her work vulgar, often stating that she introduced western and modern elements that had no place in Indian dance. However, Chandralekha had maintained that she in fact owed nothing to the western world of art. She grounded her dance in the most ancient of methods.

Navagraha and other works

Her resistance to common notions of dance did not come off as abrasive but instead, stood the test of time. Navagraha, being her seminal work, was an exploration of time and space rooted in conservative classical dance. She deliberately engaged with traditions in dance to return to the basics. However, after Navagraha, in the 70s, she took an indefinite hiatus from dance and focused on women’s rights and environmental activism. In 1984, Chandralekha’s return to stage took everyone by surprise at the East West Dance Encounter in Bombay, where she showcased three of her productions.

In 1984, Chandralekha’s return to stage took everyone by surprise at the East West Dance Encounter in Bombay, where she showcased three of her productions.

What followed were many tours and success across the world. Her enigmatic productions made waves globally and it took her to events, venues and showcases around the world including the Tokyo Summer Festival, the Hamburg Festival der Frauen; the Asian Dance Festival, among many others. In 1990, she was honoured with the Gaia award for cultural ecology in Italy and in 1991, the Dance Umbrella award in Britain. She also received the Sangeet Natak Akademi award in 1991.

Chandralekha is notable for her productions such as Angika, Sri, Lilavati, Mahakal, and Sharira among others. Sharira being her final production, was the demonstration of the self within which we exist. She exacted the idea that the coming together of sensuality, sexuality and spirituality was the pristine condition for creation, an amalgam of which already exists within each self. And by creation, she did not mean procreation, but all of creation: of thoughts, ideas, vegetation, everything and nothing. She thus centralised the feminine principle to be the origin of creation. She created a form that enabled classical dance to break away from its origins, that is, movements and understanding based in traditions rather than intuition. She juxtaposed traditional symbols with the realities of the feminine form.

The contours of her work reflect an examination and the suspension of purity, conservatism and exclusivity that Indian dance symbolised. She was uninterested in the idea of posterity or legacy. To this day, very little of her archived or recorded work remains. She lived her life in defence of the indignation that flowed through her. Chandralekha would tell her proteges to imagine themselves not as young girls but as ancient women of this land. In all her antiquity, her death too, is symbolic of the passing of a language of dance, but that which endures through parched soil, the sweeping tides of the Bay of Bengal, the flowing breast milk of a mother, and as such, through the very sustenance of life.

About the author(s)

Shreenithi Annadurai is a lawyer based out of India. Her areas of interest include art as political expression and questions of representation and resistance, drawing on rights-based perspectives and feminist media practices.