Which one of us hasn’t heard the name Frankenstein? We may have read novels or watched movies that draw inspiration from it or adapt its storyline, or heard it being mentioned across popular culture (the Phineas and Ferb title track, anyone?). Frankenstein has attained a mythic status in our society, and the origin stories of myths are often lost or forgotten as they are reinvented and reimagined over and over. Consequently, not many of us may have read the novel or know or remember that Frankenstein is a novel, written by a woman named Mary Shelley and published in 1818.

Mary Shelley is an iconic figure in literary studies, a woman who invented an entire genre in response to a challenge at the age of nineteen. A radical novel that examines the ethics of irresponsible science, the phenomenon of othering, the responsibility of creation, ambition, fallibility and so much more, Frankenstein is also one of the most thoughtful meditations on loneliness and penned in a prose that is as haunting as it is beautiful. A rich text that maintains its relevance even after two hundred years of its publication, Frankenstein is a fabulous literary achievement that inaugurated the genre of science fiction.

Also read: How Mary Shelley Critiques Patriarchy And Science In Frankenstein

/GettyImages-599958329-1bf5a3d1c2204eddb9ced96f16723860.jpg)

However, Mary Shelley’s incredible achievement is constantly denied or erased out of the popular imagination. On November 19, 2021, the New York Times published an article titled “How H.G. Wells Predicted the 20th Century” by Charles Johnson, who attributes the development of the genre of science fiction to H.G. Wells, and also to Jules Verne and the publisher Hugo Gernsback. The next morning, Twitter woke up to a virtual tornado of rebuff tweets, accompanied by some hilarious memes, blasting the New York Times for erasing Mary Shelley’s immense contribution to the genre of science fiction by neglecting to mention the fact that she published her novel Frankenstein: A Modern Prometheus in 1818.

Mary Shelley’s incredible achievement is constantly denied or erased out of the popular imagination. On November 19, 2021, the New York Times published an article titled “How H.G. Wells Predicted the 20th Century” by Charles Johnson, who attributes the development of the genre of science fiction to H.G. Wells, and also to Jules Verne and the publisher Hugo Gernsback. The next morning, Twitter woke up to a virtual tornado of rebuff tweets, accompanied by some hilarious memes, blasting the New York Times for erasing Mary Shelley’s immense contribution to the genre of science fiction by neglecting to mention the fact that she published her novel Frankenstein: A Modern Prometheus in 1818.

Mame-Fatou Niang (@mamefatouniang on Twitter) immediately pointed out that when Frankenstein was published, neither Wells nor Verne were born yet, and Edgar Allan Poe, who is also a significant figure in the development of the genre, was only nine years old.

In the last decade, retellings of myths, fairy tales, epics and classic novels have flooded the market. Located within the nexus of feminist and queer revisionism, these retellings often follow a set of patterns which include inhabiting a marginalised character(s)’s subjectivity and viewing events from their perspective, situating the events of the myth or epic in question in contemporary times or using the main plot as a trope within a novel. While deviations and reinventions from these paths do exist, most retellings take cues from these techniques.

For example, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s The Palace of Illusions retells the Mahabharata from the point of view of Draupadi, and reimagines her life, thoughts and emotions. Sarah J Maas’ explosive fantasy series, the Court of Thorns and Roses takes the themes of the Beauty and the Beast and the myth of Hades and Persephone, and uses them as plot devices in the series. Widely accepted to be a subversive form, retellings challenge heteronormative and patriarchal narratives and deconstruct them to highlight inconsistencies and the layers of prejudice and violence against marginalized communities.

The readership of retellings has exploded considerably, and every year, several new versions of our well-worn stories, myths and legends flood the market. Frankenstein has not been left behind in this trend. Rather, retellings of Frankenstein began sprouting as early as 1823 wherein Richard Brinsley Peake produced a successful melodrama titled Presumption, or the Fate of Frankenstein which Mary Shelley herself attended, which was appropriated as a moral fable (Joshi, xii). Within and beyond retellings of Frankenstein, there is enormous interest in Mary Shelley and the conception of the novel’s idea itself. In several novels, Mary Shelley, the child of two philosophers with immense influence, becomes a character herself, which has immense possibilities considering her absolutely fascinating life. However, more often than not, retellings also follow a similar line like the New York Times article that erased Mary Shelley entirely.

In The Casebook of Victor Frankenstein by Peter Ackroyd, the novel follows the titular character, Victor Frankenstein, who is the character of Shelley’s novel and the one who builds the monster. He is depicted to be a student at Oxford University, which is where he meets Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Shelley’s husband, and one of the most prominent poets of the Romantic Age. Fiction and reality blend in the novel, wherein Frankenstein builds his monster, while maintaining a deep and significant friendship with Percy Shelley. Mary Shelley, as a character, is like a pale shadow when compared to Percy Shelley’s magnificence, the ardent adoration that Frankenstein clearly feels for him and the larger than life description that Ackroyd uses while he refers to him.

Mary Shelley, in contrast, is depicted as a nervous and diminished woman, who sees Frankenstein’s monster in the flesh. Additionally, in the infamous scene wherein Mary Shelley presents her story at the contest that Lord Byron concots to ward off boredom, the story lacks, as Andrew Motion argues, the terror, the deep seated seriousness and the numerous ideas that were addressed in the original novel. The scenes are stiff, stilted and lack deftness in narrative technique, but that is another matter altogether.

Another novel, The Workshop of Filthy Creation by Richard Gadz, was published in 2021 that similarly diminishes Mary Shelley and her literary achievement. The novel follows a similar path to Frankenstein and The Casebook of Victor Frankenstein in the sense that history is mixed with fiction to weave the narrative.

In the novel, the von Frakkens are a prominent family from Prussia who have experimented with anatomy, reanimation and artificial life for generations. Among these is Victor von Frakken, who constructed a creature using limbs and body parts from corpses and imbued them with life in 1812. This experiment is said to have resulted in the death of several people, along with the monster, and Victor von Frakken was executed in 1815. The noble then makes a declaration that “the young wife of the poet Shelley” wrote a “shocking account” of the events and disguised the original events with inaccuracies, which included changing the name von Frakken to Frankenstein. In the narrative that Gadz constructs, Mary Shelley is little more than a biographer, who pieces together her novel by speaking to several eyewitnesses and nothing more. Shelley’s novel is suppressed and all copies are burnt, and both Mary Shelley and her novel are denied their literary legacy.

This practice of erasing Mary Shelley’s contribution to literature is thus not limited to ‘factual’ articles like Johnson writes in prominent publications like The New York Times. This phenomenon is located within the larger nexus and politics of erasing women, their contributions, achievements and work, from the public sphere. This practice is widespread, and we see it every day around us, to the extent that there is even a technical term for the same: the Matilda effect. Coined by science historian Margaret W. Rossiter, who refers to suffragist Matilda Joslyn Gage’s essay ‘Woman as Inventor’, the Matilda effect refers to the bias against acknowledging the achievements of female scientists and attributing them to male colleagues.

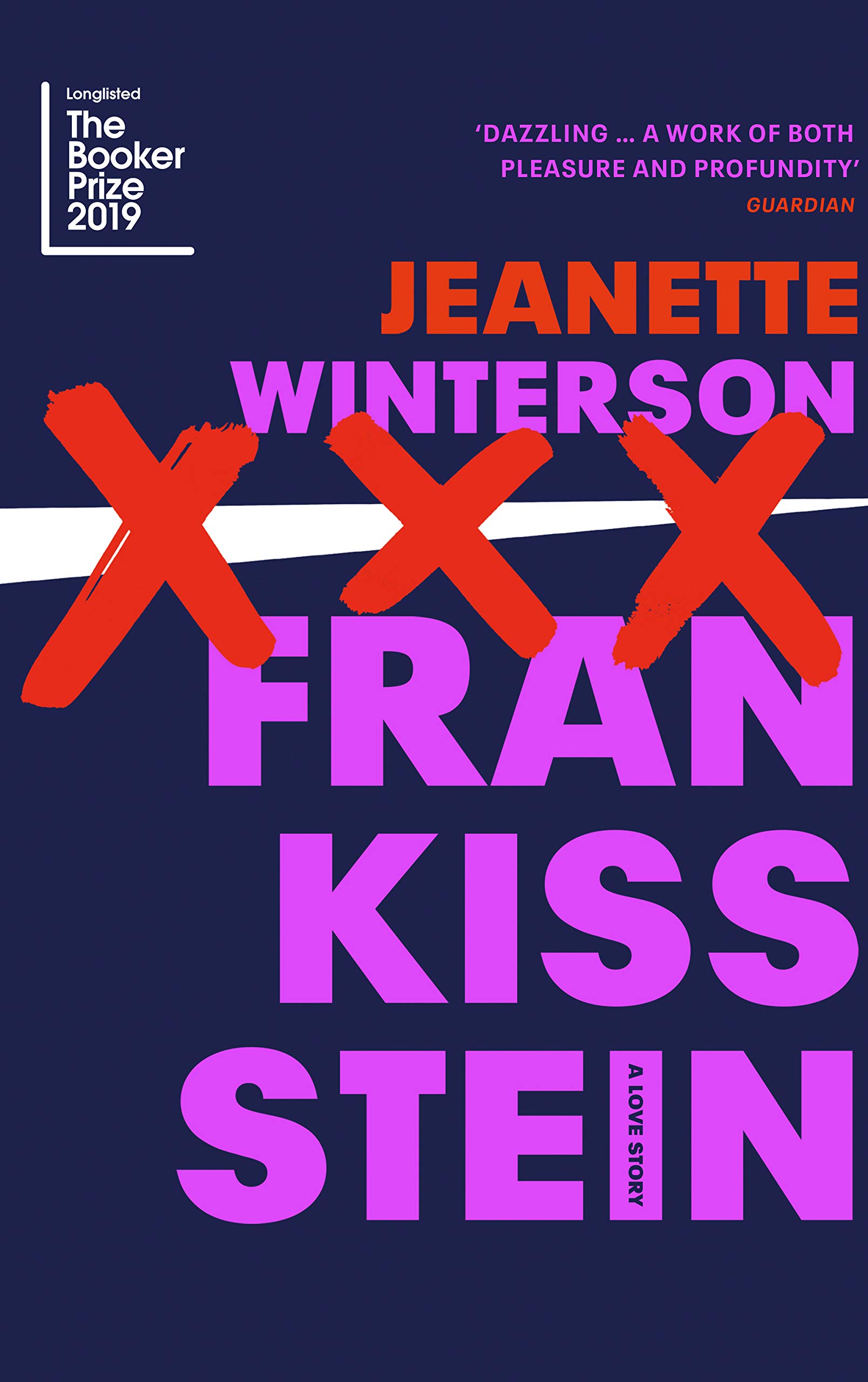

While Johnson’s article certainly credits Wells, Poe and Vernes and denies Mary Shelley, the novels discussed above resist from doing the same but in their reimagining, they reduce Mary Shelley, and deny her the “spark of her own fire” as Phillip Womack puts it memorably. Jeanette Winterson, in her latest novel Frankissstein: A Love Story, resists falling in this trap, and presents a refreshing take on both the novel and Mary Shelley.

The novel has two parallel narratives, one in which Mary Shelley lives, breathes and writes, and another one in which she is reimagined as Ry Shelley, a trans doctor. Winterson, in the nineteenth century narrative, focuses on the process of writing Frankenstein, the careful construction of the monster and the narrative, Mary Shelley’s postpartum depression, her life as she navigated the years after her husband’s death, her vision for and of the human race and so much more. Winterson’s Mary Shelley is a complex, layered character, who is deeply in love with Percy Bysshe Shelley but that is not her entire personality, like it is in The Casebook of Victor Frankenstein, and nor is she a biographer. She is a person who has deep insights into human nature, and even floats the idea of artificial intelligence.

Also read: Locating Queer Vocabulary In Literature & Cinema

Winterson, in the nineteenth century narrative, focuses on the process of writing Frankenstein, the careful construction of the monster and the narrative, Mary Shelley’s postpartum depression, her life as she navigated the years after her husband’s death, her vision for and of the human race and so much more. Winterson’s Mary Shelley is a complex, layered character, who is deeply in love with Percy Bysshe Shelley but that is not her entire personality, like it is in The Casebook of Victor Frankenstein, and nor is she a biographer. She is a person who has deep insights into human nature, and even floats the idea of artificial intelligence.

Glorifying and reverencing the canon of any genre, or displaying obsequiousness to a particular author is certainly problematic, restrictive and promotes gatekeeping. However, the main argument at play here is the systematic, conscious, continuous and circuitous process of erasing women and their contributions through historical accounts, literature and ‘fact’ based articles. Arundhati Roy’s words, “there’s really no such thing as the ‘voiceless’. There are only the deliberately silenced, or the preferably unheard”, are painfully accurate and resonant in today’s socio-political climate, and efforts towards highlighting the same need to be similarly rigorous in order to overcome this collective amnesia through collective restoration by amplifying voices, contributions and inventions, and calling out those who deny the same.

References

Ackroyd, Peter. The Casebook of Victor Frankenstein. Chatto and Windus, 2008.

Gadz, Richard. The Workshop of Filthy Creation. Deixis Press, 2021.

Gray, Chloe. “The Matilda Effect: The Brilliant Women Whose Achievements Were Erased from History by Men.” Stylist, 20 May 2019, www.stylist.co.uk/people/matilda-effect-what-is-it-erasure-achievements-by-women-susan-sontag-hidden-women/267412.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus, edited by Maya Joshi. 2002. Worldview Critical Edition. Delhi: Worldview.

Winterson, Jeanette. Frankissstein: A Novel. Reprint, Grove Press, 2020.

Womack, Philip. “The Casebook of Victor Frankenstein by Peter Ackroyd.” New Humanist, 8 Sept. 2008, newhumanist.org.uk/articles/1870/the-casebook-of-victor-frankenstein-by-peter-ackroyd.

Meghal Karki is a research scholar at the School of Letters, Ambedkar University, Delhi. Obsessed with folk tales, fairy tales, fantasy and fiction, and a novice Angela Carter aficionado, she is always looking for a good book to read. You can find her on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

Featured image source: thoughtco.com