Having been trained in law, Suchitra Vijayan initially worked at the United Nations war tribunals in Yugoslavia. Co-founded the Resettlement Legal Aid Project in Cairo, Suchitra is also the founder of the Polis Project, a research and journalism organisation. Nine years ago, she began documenting stories from her travels along the borders of India.

“India’s intellectual, journalistic, and literary landscape is profoundly problematic and alienating. It’s feudal, entitled, and cannibalistic. This is a profoundly alienating place for anyone without the networks of privilege and resources. Now imagine how it would be for someone from a Dalit/Bahujan, Muslim, Adivasi, or working community to try to make inroads. There are enough stories of people parachuting into communities to do ‘human interest stories’.”

Suchitra Vijayan

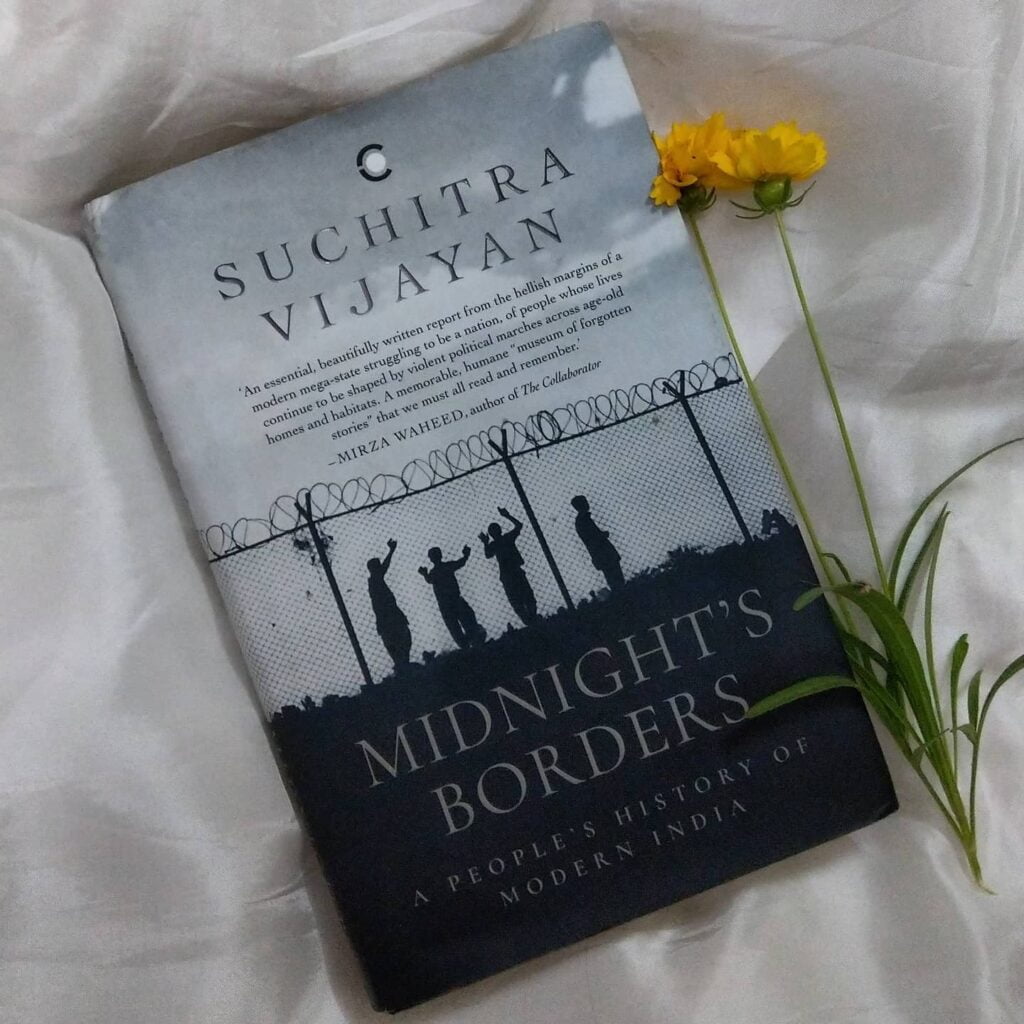

Her writing and award-winning photography culminated in Midnight’s Borders: A People’s History of Modern India, which was recently shortlisted for the Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay NIF book prize.

Suchitra Vijayan talks to FII about Indian politics, communal violence, marginalisation and her book Midnight’s Borders: A People’s History of Modern India.

Q: Since publishing the book last year, what reflections have you had—given that its relevance is increasingly ascertained by 2022’s interpersonal and geopolitical violence?

A: This geopolitical violence is not new, there’s a long bloody, brutal history to this–a cyclical, ongoing and never-ending history. I think the way that news and mostly disinformation makes its way to us, we think of violence in very particular ways—as disjointed. One of the reasons why this book was written was to step back: to say that this violence that you and I listen to and encounter is not new— to say that this violence is not new. And that violence is often abetted by the state and goes unpunished. That was my starting point.

It took me 8 years to write the book. When the book finally came out, India was undergoing the deadly 2nd wave. According to a new World Health Organization report, we lost as many as 4.7 million people in India. The government, of course, denies this. So we might never know the true extent of this loss. It was just a sad moment, and I couldn’t celebrate a book when there was so much human tragedy playing out.

So the first reflection is this idea of where we are right now: as people, as a society, as a community. How does one think of violence, how does one make sense of all this, how does one retain a sense of—not exactly humanity, but rather—empathy for the other? I think these are fundamental questions of freedom and dignity.

Second, we can no longer have certain conversations…conversations are now impossible. Some things are just not discussed anymore. Worse, we have been disciplined to accept injustice and inequality as given.

Also read: Whose Stories Are Told In Indian History?

The third thing is: we’re going back to relitigating everything. There was an NDTV programme, where somebody said “Should India’s constitution be secularist? Is secularism a good thing?” This is such an insidious conversation to have; this was even before Adani bought it. This is not the violent right wing and their siege; it’s centrist and liberal media that is also relitigating history, deconstructing the core values of the constitution.

Q: You had to deal with a lot of ethical considerations as a writer and photographer, which echo throughout your and your fellow journalist’s work, as evaluated in your book. How do you think the media ought to responsibly report on people’s lives and experiences?

A:I don’t think an ethical or moral compass exists now…I don’t know if it ever existed. This idea of “responsibility” gets obfuscated in many ways. The publishing landscape, including Indian publishing, is deeply flawed—it is upper class, upper caste, and deeply alienating for anyone who doesn’t come from already established and existing networks of privilege.

India’s intellectual, journalistic, and literary landscape is profoundly problematic and alienating. It’s feudal, entitled, and cannibalistic. This is a profoundly alienating place for anyone without the networks of privilege and resources. Now imagine how it would be for someone from a Dalit/Bahujan, Muslim, Adivasi, or working community to try to make inroads. There are enough stories of people parachuting into communities to do “human interest stories”.

Also read: ‘Examining My Caste And Its History Is Eye-Opening’: A Personal Essay On Casteism And Ancestry

This means that, for the longest time, the depiction of violence and marginalised communities has been problematic. Firstly, when we talk about violence, we often talk about it only as “communal” violence, as if both communities have equal strength and power. They don’t. We still argue if something should be a massacre, a pogrom, or a riot. Often, we settle comfortably into describing things as “communal riots” instead of saying that it was a state-abetted violence, a pogrom, or a brutal massacre. The word terrorism, for instance, is used almost exclusively to refer to a particular community—but fails to refer to state-enabled terror or the terror deployed by majority communities.

In terms of violence, there is also this tendency to photograph and display the bodies of marginalised communities when they experience violence. We don’t document violence against the privileged like we would report violence against those without power.

How violence against women and girls—and even how sexual violence against men and boys (something we don’t even talk about enough) is depicted—is all seriously problematic.

A consistent ethical framework within the media hasn’t existed for a long time. Over the past 15 years, small democratisation through social media has enabled challenging these practices.

Q: What struck me about your work was its immersive style. How did you achieve empathy in your writing, without the privileged lens that is common in journalistic canon?

Empathy is taught by our communities; we are brought up with it. Growing up I was surrounded by people who emphasised the community over anything else. I fear we are losing that cosmopolitanism of small places.

The book was originally going to be a photographic body of work, which changed when I started writing. Then my agent said, “Suchitra, you know, I think you’re hiding behind your academic language. You need to write what you see—that’s why you started this project.”

I had to write and rewrite this book so many times. It took a long time to get the voice right.

So I don’t know if it was empathy so much as just building a relationship with people. The people whose lives are not just materials for the book, who are, in some ways, your co-conspirators in trying to make sense of the social reality.

Source: Eastern Eye

Q: What was your goal with writing the book in the beginning and how did it change and drive you throughout those 8 years?

A: Writers are very strange creatures. No one would put themselves through the agony and pain of writing. One of the reasons I kept writing was of course all the people I met: their love and time and generosity. Second, there were times when I ran out of money, when some said that such a book would not be published, when some declared that such a book could not be written. I was much younger when I took on this project, so I wanted to prove those people wrong.

Also read: The History Of The Colonial State And The Unmaking Of The Tawaif

I don’t think there’s just one emotion that drives a writer to finish writing. Love, passion, anger, the desire to make a point about something. At the end of it, I felt that I learnt more about myself, more about my home, I had become—if not a better writer, an infinitely better human being, which is to say that one realises that there’s always a Longue durée that one needs to consider, crave out time and space to think, train oneself not to always react.

When I finished writing, I had become much richer in many ways—not in a material way—but through a community. No one can write a book alone. You need a community of people to support you.

Q: As you wrote this book, you don’t hesitate to meditate on how your personal life bidirectionally impacted the book. How did writing this book affect you?

A: I lost friends, saw my father go through a transplant, and I gave birth. I left my 18-month-old daughter to travel and finish this book. This book ate into so much of my life.

Can you write about loss without living? The mortality of someone you love affects how you write. Then you sit in a room with a mother telling you that she has no idea what happened to her son and has no way of knowing if he’s ever coming back. That changes how you write and photograph a place.

Similarly, motherhood changed me; it radicalised me. You become responsible for a human being. Because you are constantly thinking about the ethical universe you are bringing this child into— What values do you teach this child? How do you protect this child?

I had a very stable home to come back to. That capacity to be able to go away and then come back profoundly affects how you write because then you are still rooted. It’s impossible for a writer not to be affected by their personal life.

Q: You frequently describe certain borders as porous. Do you think the future is borderless? Is that a probable solution? What do you think the future holds?

A: This is a very loaded question. Let’s start with a very simple statement that everyone can agree on: the way we’re living right now cannot continue. It’s not sustainable, it fractures who we are, chips away and erodes what it fundamentally means to be human.

I can’t think in terms of the future being “borderless”, I can only think in terms of “fracturing.” There are already about 20 million climate refugees around South Asia’s borderlands. Parts of Pakistan have already been consumed by the water. When fires burn down large swathes of what were people’s homes—what borders will you impose when climate change will fundamentally remake them? So the question is not: will the future be borderless? Instead, we need to ask what fate awaits us.

The pandemic showed us that crises and recurrent disasters that annihilate our lives are here to stay. Accompanied by this globally, democracies are becoming more authoritarian and stripping people of their citizenship—reducing them to subjects, entrenching the fault lines of inequality. In the middle of significant change, this fraught system cannot exist as it is. So now, how do we respond to this?

The world we know is already being remade in ways we can’t fathom. Why don’t people see the ground shifting beneath their feet?

Q: Speaking about the content of the work, by including under-represented perspectives on the frequently debated partition and border laws you present a novel perspective to journalistic canon. How do you think this shapes climate justice? And what does this mean for on-ground communities, governments, armed forces, and other institutional stakeholders?

A: I don’t agree with this kind of framing, because it’s not that underrepresented people don’t have voices. They’re screaming all the time, it’s just that we don’t listen to them. Some of the oldest resistances in our nation are those communities who have been fighting for their own homes from militarisation who seek to exploit their mineral rich home land for mining. If you think about communities in resistance to immense violations, they’re all interconnected to climate justice.

Also read: Book Review: Looking Through Dalit Sahitya And Ambedkar

I set out not to give voice to the voiceless, my aim was to put an ear to the ground and listen. I think it’s the other way round, these communities have always been speaking, writing, documenting, teaching—we must simply listen rather than “represent” them in any way.

We also need a fundamental reframing of language. We can’t continue to see this in neo-liberal terms like “stakeholder.” I think the usage of this kind of language is ineffectual; it’s emptied of imagination. No one is a stakeholder here—these are people, humans, citizens, who have been deprived of what the Ambedkarite constitution promised them.

True societal change has always emerged from the ground-up, with communities fighting for their own freedom and dignity. We must realise that it’s the grassroots media, who represent themselves, document what mainstream media ignores, and bring to notice what is important

As a trained barrister, I used to believe in the concept of justice—but now I simply call this freedom and dignity. This language drums the idea of the fundamental importance of justice, and such language is inalienable: it can easily be defined and empathetically understood. I think freedom and dignity enables us to really go beyond in our political imagination—beyond just electoral politics. And our language helps us imagine a vision that is truly just, beautiful and ethical.

The interview has been paraphrased and condensed for clarity, at the interviewer’s discretion.

Suchitra tweets @suchitrav. We thank her for her time, patience, and illuminating insights into her work. Thanks to The New India Foundation for sending across a beautiful copy of the Midnight’s Borders.

Excellent interview, brave insights and critical reflections!