Trigger Warning: Mentions Gender Based Violence

Slut-shaming is a form of gender based violence that minority genders particularly women have faced throughout history. Slut-shaming can include verbal abuse, street harrsement, cyberbullying, and even physical violence.

The term “slut” is used to describe women who are “perceived” to be “sexually promiscuous,” or violate traditional gender norms, often resulting in social stigma, violence and condemnation.

In her book Slut Shaming and The Sex Police: Social Media, Sex, and Free Speech, Soroya Chemaly writes, “When women, whether offline or online, demonstrate self-control over their sexuality, there is frequent indignation; when they are harassed or abused, there is frequent ridicule and humiliation.”

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health probed into the physical effects of slut-shaming on adolescents and concluded that slut-shaming results in various physical ailments- from low self-esteem to anxiety and depression.

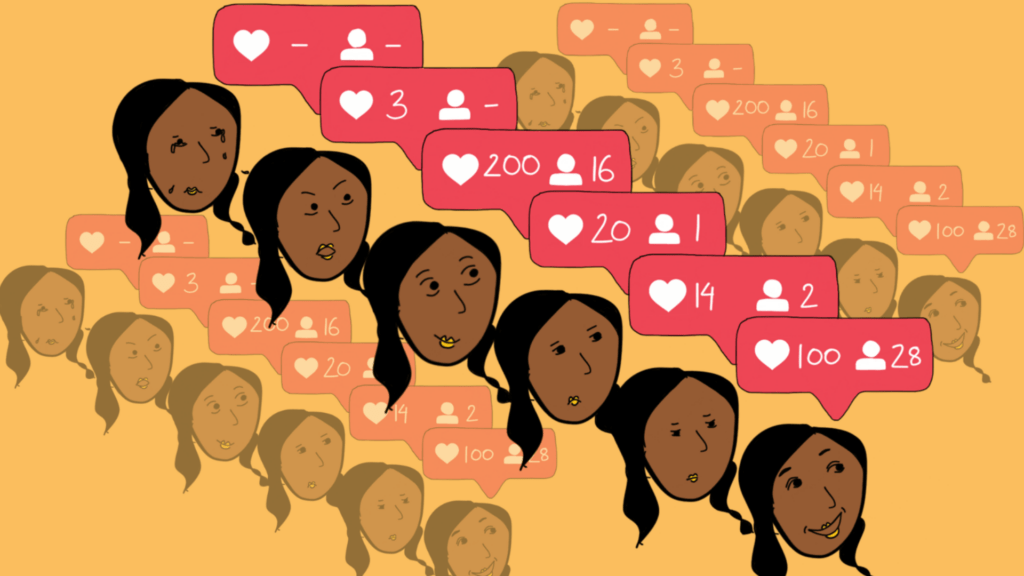

Slut shaming can have serious negative consequences on women’s mental health and well-being. In the context of Instagram women often post photos of themselves and their bodies, resulting in slut shaming in the form of derogatory comments, online harassment, and even cyberbullying.

This can lead to feelings of shame, anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem, which can have long-term impact on women’s mental health. Additionally, women who experience slut-shaming may also be more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviours or develop unhealthy relationships as a result.

Elisa Tate in Challenging a Woman’s Digital Agency: The Frequency of Slut Shaming in Social Media writes that online environments are oppressive and gendered places where women are pressured to uphold patriarchal ideas of femininity while also being sexualised by men.

The idea that women’s bodies are public property that may be viewed, talked about, rated, and shared is encouraged by patriarchal rules, social conventions, and a photo-heavy online world. Common punishments for women and girls are made worse by social media, generally through slut-shaming.

Slut shaming aids in solidifying and maintaining gender standards and stereotypes and enforces the prevalent rules of acceptable femininity by socially sanctioning behaviours or attitudes that go beyond the accepted norm for romantic, sexual, or gendered performance.

Slut-shaming is not just Cyberbullying. The gendered component of this form of prejudice runs the risk of being hidden if slut shaming is framed as a type of cyberbullying. Young women’s social surroundings influence gendered norms and behaviours. Slut shaming aids in solidifying and maintaining gender standards and stereotypes and enforces the prevalent rules of acceptable femininity by socially sanctioning behaviours or attitudes that go beyond the accepted norm for romantic, sexual, or gendered performance.

For example, sharing photos or selfies on Instagram can invite a lot of responses, and often not pleasant. In the Economic and Political Weekly, Nishant Shah writes that selfies and photographs are not only cultural artefacts but also born as a result of growing digitalisation and produce new regimes of control online. This gendered cyber-hate takes various forms such as non-consensual pornography, slut shaming and revenge porn.

Gender trolling is not new, it has only grown with growing digitalisation. In 2018 National Dialogue on Gender-based Cyber Violence organised by IT for Change, and the Advanced Centre for Women’s Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), stated that “gender-based hate speech, that may or may not be sexual, is a form of gendered violence that seeks to deprive persons from discriminated gender locations of dignity and equal participation in society.”

Despite the growing awareness of slut shaming in contemporary society, there remains a significant gap in our understanding of its effects on women’s well-being. The stigmatisation and derogation of women who are perceived as sexually promiscuous may contribute to a range of negative outcomes, including decreased self-esteem, increased anxiety and depression, and diminished sexual agency. Yet, there is limited research on the extent and nature of these effects, as well as the factors that mediate or moderate them.

While concluding a study on the effects and horrors of slut-shaming on women who have an active presence on Instagram and seemed to have flouted the ‘rules,’ of patriarchy, I found the results deeply worrying. The lack of institutional support coupled with the long-term results of such abuse led to a decreased participation of women on Instagram, a space designed to promote gender equality and participation.

However, there also emerged stories of hope, of resistance to this shaming and the refusal to succumb to patriarchal notions of society.

In the course of this research, I interviewed 20 urban women between the age of 19-25. When I undertook this research, I had some idea of the stories that could emerge around the prevalence of slut-shaming and the forms that it can take on Instagram, but the intimate experience and the effect that such shaming had on women were truly eye-opening. Whenever I brought up this topic, everyone I talked to had a story and indeed felt very strongly about this problem.

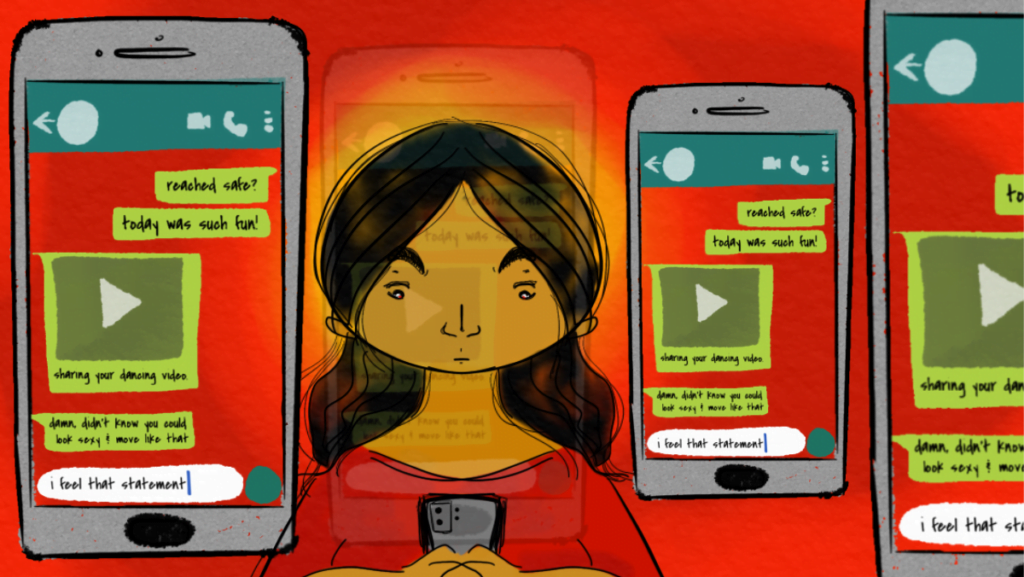

One respondent mentioned, ‘I posted an anonymous message link and almost every message had to do something with my body. From offering money to see my breasts, describing in vivid detail how someone wants to engage with me sexually, calling me characterless based on my clothing choices, saying I get sexually assaulted because I’m asking for it by having bigger breasts and rape threats.’

For some, posting photos or anonymous messages links led to slut-shaming, while for others, even posting against slut-shaming resulted in getting abused. Another respondent said, ‘I uploaded something on slut shaming and in return I got slut shamed. It was a teenager and I reported the account but couldn’t get the person removed since it did not go against the community guidelines.’

Another respondent also shared how identities often masked by the anonymity of a fake profile can engage in incessant slut-shaming and Instagram’s community guidelines are seldom of help.

While the responses of women showed the intrusive nature of the problem, they also threw light on the effect these comments had on the victim’s mental health and the coping mechanism they adopted. To analyse in depth these effects, I asked the respondents how they felt when were subjected to instances of slut-shaming. The response received was multi-faceted and provided an insight into the psyche of the victims.

One participant adds how women often choose to ignore such sexist comments rather than indulge in fighting them.’Sometimes I don’t care & it’s funny but sometimes it just makes me angry & furious.’

Another added to this, ‘It has almost no effect on me since I’m used to this. I simply choose to ignore it.‘ This is however just one side of the coin. This response of ignoring has stemmed from a regular subjection to slut-shaming comments without any effective action against such harassment.

Slut-Shaming can lead to feelings of extreme degradation or repulsion against one’s body. ‘Like I’m nothing more than a sex object. Like no man will ever look at me and see a person. Like I have nothing to offer except my body,’ mentioned one respondent.

Slut-shaming is a serious issue that women have to deal with daily, even though it seems to be casual banter with no actual consequences. Being judged all the time destroys their mental peace and severely damages their perception of themselves and how they look. It also makes women feel invisible and at the mercy of others on a digital platform like Instagram with no real regulatory measures, as one respondent elucidates- ‘I felt not heard. I felt that even if I came out with this, no one would be there to help me out with it.’

An important aspect of the continued inequality between men and women and the persistence of sexist ideas is how women are seen in society. Simone de Beauvoir, the influential feminist philosopher and author of The Second Sex described the phenomenon of men constructing the concept of woman from their own experience rather than from what women are in reality, stating that women are framed as “the Other,” while men are the self and subject.

Women tend to oppress other women, thinking that that would make them more liked, more appreciated by the patriarchal society. Women assert that we are better than the women they shame, to remove themselves from the conventional traits that we have been conditioned into thinking are bad.

This othering is ingrained even in women, who aim to abuse and victimise other women. It is an acknowledged truth that patriarchy is so ingrained in the psyche of women that women often become a part of this ‘Othering’ by becoming an agent in their oppression. Women tend to oppress other women, thinking that that would make them more liked, more appreciated by the patriarchal society. Women assert that we are better than the women they shame, to remove themselves from the conventional traits that we have been conditioned into thinking are bad.

All respondents said that slut-shaming affected them in a certain way. It was heartbreaking to read their responses, as it stems partly from anger towards this regrresive patriarchal and sexist system and partly due to the helplessness of women to regulate such behaviours. When a woman feels sexual shame, she is unaccepting of herself and expressing a feeling of defectiveness leads to developing the idea that she is unloved and rejected.

Sexual shame has the potential to generate inner turmoil, anxiety, stress and painful emotions, In turn, these can bring about low self-esteem and mental health issues. Feelings of low self-esteem were common, often supplemented by various other side effects. ‘I was depressed for a long time when I was in high school and I was labelled and termed since then because I was different from other girls. I was always an open and extrovert girl back then which was misinterpreted and the general response of kids back then was ‘sluts.’ It ruined my self-esteem and I was depressed and took help and it continued for a year.’ mentioned one respondent.

Researchers who examine how media portrays violence against women have often noticed a virgin-whore dichotomy in the digital platform, which depicts the victim in a way that implies she was complicit in the attack. Respondents said that they often tend to change how they dress, stop using social media, show tendencies of self-harm and even think twice before uploading anything on Instagram or portraying their true selves. One respondent even changed her account from public to private and removed her followers.

For most participants interviewed for this study, the first coping mechanism was always ignoring such comments and trying to not let them affect them. Excluding themselves from social situations and silence was the chosen option by many. However opposite responses also emerged. One respondent said, ‘Focusing on the thought that what others think of me does not define me as a person. Also, a slut shamer is someone insecure deep down and they are projecting themselves when they engage in such behaviour. It’s them, not me.’

Another added, ‘I stopped giving a damn about other’s opinions. I started talking to people about how I feel when they react in such a way. Mostly not giving a damn. because that is better than shutting an infinite number of mouths.’

The responses of this research show the pressing need for platform owners, legislators, and society at large to address the issue of Instagram slut-shaming. Women should be able to express themselves online without worrying about criticism or abuse, thus efforts should be taken to make these spaces safer.

Very good