As a member of the Advisory Committee of the magazine In God’s Image, Jessie Tellis-Nayak tried to question the absence of women in the church and society, carrying responsibilities as the structure and teachings propagated by a patriarch.

Her life is an example of grit and determination for women’s rights. A battle to transform society focused on delivering primary rights for women, from getting an education to setting them free from subjugation. The basic right to gain education is a fundamental right under Article 21A, where the state is responsible for providing education to all children from six to 14 years. This prospect resulted in female enrolment in higher education shooting up by 32 percent from 1.57 crores in 2014-15 to 2.07 crores in 2021-22.

From a middle-class family

Jessie Tellis-Nayak was born into a middle-class family in Mangalore, Karnataka. She was the first in her family to use Nayak along with the Portuguese surname to underscore her customary tradition. In academics, she pursued education abroad to fulfil her dream on her terms, defying marraige. She completed her Master’s and Doctorate in social work from the Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C. During her stay in the country, she worked with marginalised people in shanties and joined in protests for Black People for their basic human dignity.

Her return to India came after listening to a speech at Lincoln Hall, where Martin Luther King gave his iconic lines, I Have a Dream, and in the process, declined to accept the lucrative positions offered in the US. Employment in India came in 1965 at the Indian Social Institute based in Delhi, where her primary work revolved around tribal communities from several states. Later, an organisation called Vikas Maitri was instituted to focus on developmental programmes braced by professionals from the tribal communities. Where in this programme, she realised the representation of women is lesser at planning and decision-making levels in development bodies. This representation could be enabled by opportunities, moral support, and necessary skills for their development work to bring out the potential of women.

The year was 1975 when Jessie Tellis-Nayak was appointed as the director of the Women’s Development Unit at the Indian Social Institute (ISI); a programme called the Grihini Training Programme was initiated, which became renowned in the nation. The aim of this programme was to provide education to illiterate girls who didn’t receive basic education due to poverty and issues within families. Apart from organisational community and welfare support for women, Tellis-Nayak has 16 published books and several research articles. There are books that are written by co-authors, and the notable ones are Emerging Christian Woman, On Legal Bondage, Women in Church and Society, and Indian Women Forge Ahead.

Her return to her birthplace came in 1982, when a group of committed women from the Catholic community created the Women’s Institute for New Awakening (WINA). The objective is to create awareness of women’s condition and promote feminist theology. This drudgery resulted in connecting with other women’s groups, libraries designed for women to read, and a newsletter introduced to disseminate information on women’s situation under WINA Vani. Her initiative impacted some of the cities, such as Bengaluru, Mangalore, and Mumbai.

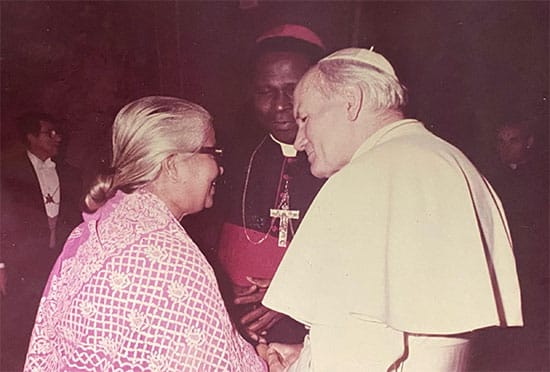

Her endeavour was recognised at international conventions, where the Asian Conference held in Tokyo in 1970 on ‘The Church and the Development,’ selected her as a delegate. There were meetings organised in Rome and at a colloquium in Belgium, which she attended, including the Women’s Conference in Nairobi, Kenya. Her involvement was also a resource person in workshops for rural women in Manila, Philippines, and Bali, Thailand.

Decision of the protagonist

Jessie’s initial work was divided into two parts, collaborating with the Indian Social Institute (ISI), Delhi. One part discussed women in India, and the latter portion focused on women in the church. Her article honours the efforts of women who not only manage the household and care for everyone, including their in-laws, but also actively participate in farming alongside their spouses.

The sustained purpose of a single woman not joining an order or secular institute or deciding not to get married is adored. She was constantly told by a priest to get married, and one day, her reply came with an exasperation: “You respect my vocation, and I will respect yours“. Later, the priest never hounded her.

A Pune-based organisation, Ishavani, supported Jessie Tellis-Nayak and her companion editors. Their task was to contact women known for their commitment to issues and collect their testimonies and views as a manuscript. The book’s title was The Emerging Christian Woman—Church and Society, which seemed conservative; their contributors freely used words such as feminism and feminist.

Jessie wrote 14 ways for women to raise their consciousness with the help of new organisational approaches and new types of programmes for Women Development Workers. She argued that an activist approach is required to campaign for rights and redress grievances, which came from the survey conducted by Caritas India in 1982. She also highlighted the importance of women as participants in the church in accomplishing development projects.

The late 70s and early 80s transformed the lives of women under the feminist movement. The endeavour of activists such as Jessie Tellis-Nayak has changed the policies for women.

About the author(s)

Asif Iqbal works as a Research and Policy Associate at the Council for Social and Digital Development, Guwahati.