The rise of the right wing populist regime in the Indian State has brought alongside numerous disruptions and discontinuities in the previously existing systems and sectors. One such sector which has been the zone of high disruption is the Education System of our country. With multiple degree programs being nullified to National Education Policy 2020 to the discontinuation of M.Phil Degree, the education sector has been disrupted severely.

The major hit is being faced by the humanities domain, wherein universities like JNU, DU, JMI are facing structural damages while on the other hand “scientific research on cow dung, urine, and milk” is being funded and promoted by the Indian State.

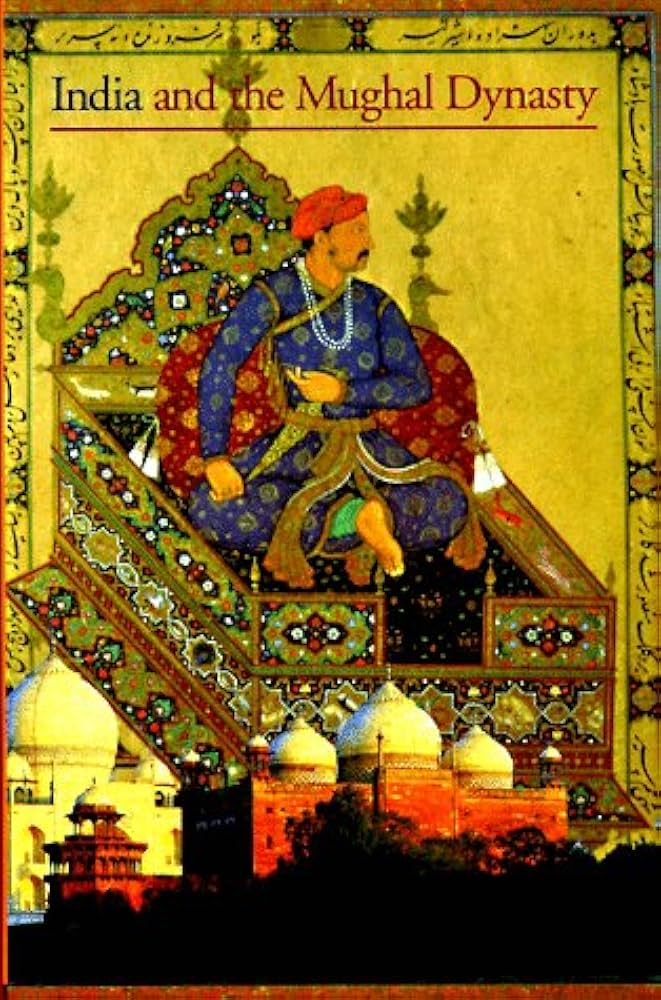

This erosion of academic spaces in higher education is now increasingly reflected in the school curriculum as well, signaling a systemic attempt to reshape historical narratives from the ground up. Amongst all these, a major blow to the education sector, specifically the humanities domain, is the recent move of NCERT to remove the chapters on “Mughals and Delhi Sultanate” from the Social Science Book of Class VII.

The specified content would be replaced by ancient Indian Dynasties and “sacred geography”. The recently released book under the title Exploring Society: India and Beyond appears to be the first part of the publication. The mentioned changes are expected to be included in the second part of the publication. This act clearly portrays a deeper undercurrent of a larger project i.e. the act of erasing medieval history from the textbook will eventually lead to the erasure of the history of the Medieval Era from the memories and consciousness of the people.

The current regime, ever since it came into power, has been practicing the “otherisation” in multiple contexts. A vivid example of the same is the exclusion of muslims under the CAA of 2020. The speeches of numerous ministers including the PM have time and again created an image of “others” in the context of Indian State. The usage words like ‘Jyaada Bacche Paida Karne Wale‘, ‘Ghuspaithiya‘ and many more vividly portrays the communal bifurcation, the Indian State is subjected to.

Instances of hate speech against minorities jumped 74% in India in 2024, peaking during the country’s national elections, according to a new report. This communal framing is not limited to contemporary politics alone—it is being extended into the past, reshaping how history is taught and remembered. The recent curricular changes, particularly the removal of Mughal and Delhi Sultanate chapters, reflect an attempt to align historical narratives with this divisive political vision.

The political project behind reforms in education in India

Renowned Historian Romila Thappar begins one of her recently published books Our History, Their History, Whose History? with the words, ‘Nationalism encourages a variety of narratives about the past of the society from which it emerges. These narratives differ as their intention is not so much to focus on any particular history, but to provide ancestry to the communities involved in the nationalist enterprise of the society, and to give the society a focal point to where it should head.‘ The conflagration of hypernationalism inevitably requires a spark; often found in the otherisation of people, communities, regions, religions, and now, history itself.

The conflagration of hypernationalism inevitably requires a spark; often found in the otherisation of people, communities, regions, religions, and now, history itself.

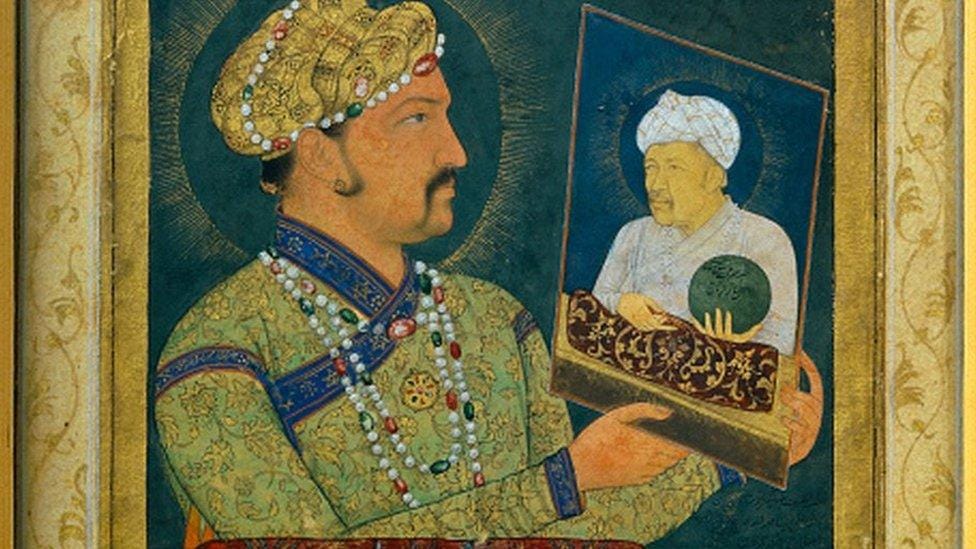

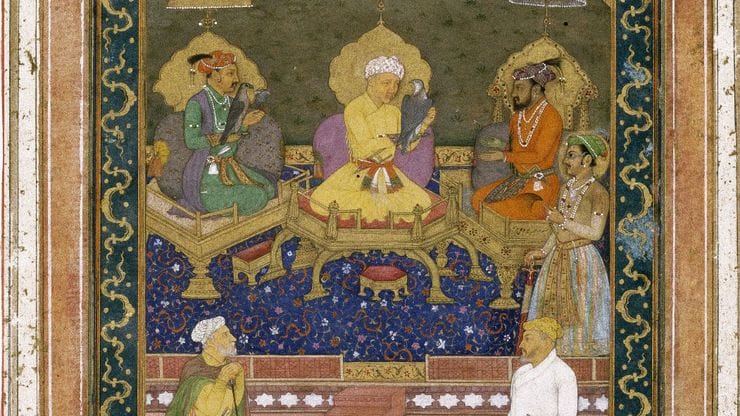

The Medieval Era in the Indian subcontinent forms a crucial bridge between ancient traditions and the modern nation we live in today. It was a time of significant cultural, architectural, and political developments. This period, especially its second half, was shaped by the rule of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire—dynasties that contributed immensely to India’s composite heritage.

However, the recent removal of this era from school textbooks is not just an academic oversight but a deliberate political move. These rulers, often targeted by the current regime for their Muslim identity, are now being erased from the mainstream historical narrative. Such exclusion not only distorts our understanding of the past but also weakens our ability to engage with the complexities of our present.

Ideological state apparatuses and the manufacturing of compliance

The deliberate attempt to rewrite history, especially in the minds of young students, is far from a minor act, it is an act of deep political significance. French philosopher Louis Althusser, in his much notable framework of ‘Ideological State Apparatuses‘ (ISA), provides how institutions like family, religion, media, and especially education function to reproduce the ideology of the ruling class.

Unlike direct repression, ISAs work subtly by shaping how people think, behave, and accept the existing social order as natural. Among all ISAs, Althusser identifies education as the most powerful, because it operates over a long period and targets children at an impressionable age. By controlling educational content, the state ensures its ideology becomes common sense, unquestioned and deeply rooted.

The replacement of medieval history with the geographical and the pilgrimage sites will eventually lead to the acceptance of the culture and traditions in young minds (who are the future of the upcoming India). The dismantling and re-writing of the history by the nationalist forces is a nascent activity. A complex web of multiple strategies and combination of ISAs (Education, Media, Entertainment, Family, Internet) serves the purpose of inculcating the ideology of the ruling class among the citizens.

A complex web of multiple strategies and combination of ISAs (Education, Media, Entertainment, Family, Internet) serves the purpose of inculcating the ideology of the ruling class among the citizens.

The flux of Bollywood movies with Mughals being the antagonist, though the history of the events in such movies are erased and manipulated as per the ease, is playing a vital role in the larger project of “otherisation”. Though Althusser could not anticipate the future of technology, Social Media and internet alongside the Educational institutions are the major ideological state apparatuses. This system of ISAs vanishes any probability of existence of physical or repressive imposition of the ruling ideology; the usage of violence or state law. The acceptance and compliance works in the domain of ideology, shaping the ideas and norms of an individual slowly and gradually but affirming them for a longer run.

Another subtle yet significant remodelling by NCERT in the education system, is the recent titling of NCERT textbooks. Several new books for Class VII have been given Hindi titles, regardless of their medium of instruction. Even English textbooks for Classes II, III, and VI are now titled Mridang, Santoor, and Poorvi respectively. While India’s Constitution officially recognises 22 national languages, this selective promotion of Hindi in educational materials clearly portrays an attempt to build a linguistic hegemony.

It is not just about naming, it is about framing a cultural identity rooted in a singular language. This practice of prioritising one specified language over others brings the heterogeneity, diversity and plurality of the Indian State at stake. This act reflects a calculated attempt to construct a dominant national identity, one that draws a clear line between “us” and “them.” Much like historical erasure, the imposition of a dominant language serves to marginalise diverse voices and reinforce ideological conformity.

Urdu has always been an integral part of the Indian State, from the era of Independence even to the recent times. The evolution of the language has also seen the building up of the Indian State.

The degradation of the Urdu language is one of the prominent examples of the same. Urdu has always been an integral part of the Indian State, from the era of Independence even to the recent times. The evolution of the language has also seen the building up of the Indian State. But, the recent trend of aligning the existence of the Urdu language with the “islamic” identity has left this beautiful language into margins, erasing its shared legacy in India’s literary and cultural history.

Voices at the margins: resisting a singular India

What we are witnessing currently is not a meagre change in textbooks, it is a quiet but powerful shift in how young minds are shaped. When education begins to mirror the interests of those in power, it stops being a tool for inquiry and becomes a mechanism of control. By narrowing the lens through which history, language, and identity are taught, the space for disagreement and diversity slowly disappears.

This is not about one chapter or one language, it is about who gets to tell the story of India and who gets left out. The real challenge now is to hold on to education as a space for many voices, not just the loudest one in power.

About the author(s)

Harsh Bodwal teaches Social Science and English at a CBSE-affiliated school and holds an MA degree in Political Science from Jawaharlal Nehru University. His research explores how caste, patriarchy, and capital intersect with the various institutions to shape and often constrain democratic processes.