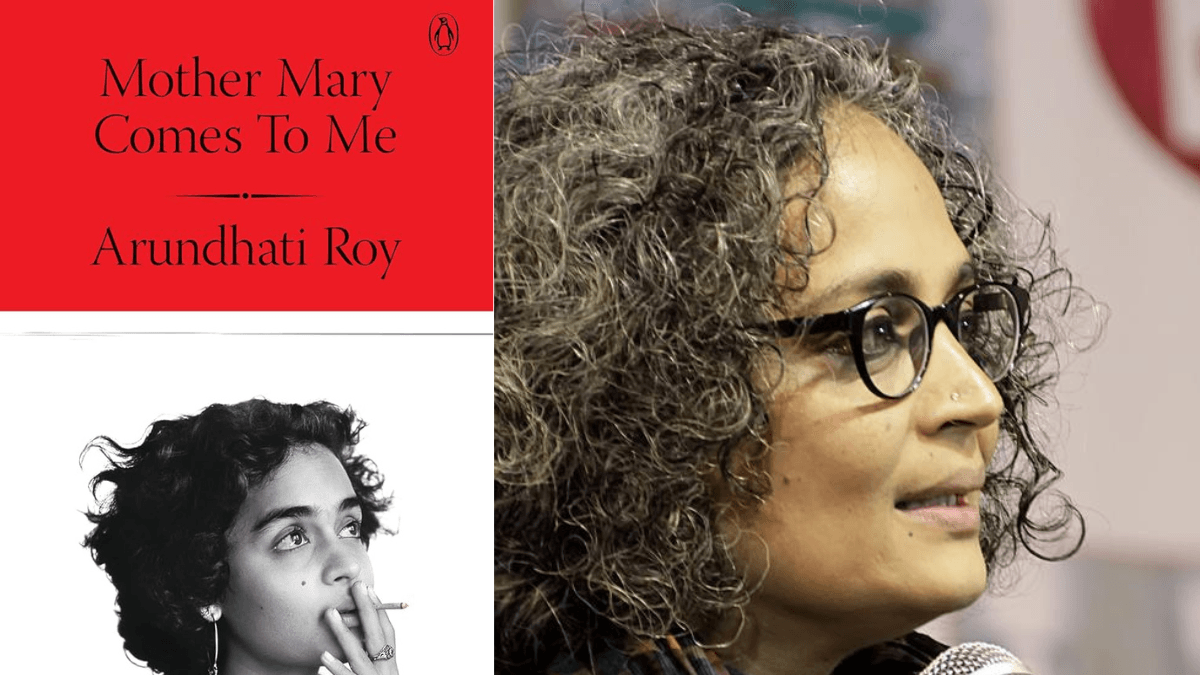

There is something deeply disquieting about Arundhati Roy’s latest book, her first memoir, written in the shadow of her mother’s death. And yet you don’t have to be a reader or writer to fall in love with it.

Mother Mary Comes to Me is bold, as any memoir must be, but also paradoxical. Roy manages to be utterly confessional and yet curiously elusive at the same time. Her prose embraces the “David Copperfield crap” that Holden Caulfield once railed against in The Catcher in the Rye — the everyday humiliations, triumphs, and awkward textures of childhood. But Roy, unlike Caulfield’s caricature of phoniness, achieves an authenticity that is vulnerable, unsparing, and never sentimental. You will want to be her best friend; you will want to know her better.”

The forced feminist

This is not simply Arundhati’s story. It is the story of her mother, Mary Roy — formidable, contradictory, impossible to contain. To a casual internet search, she appears in history as an “educator.” Arundhati paints her instead as a woman who refused the prescribed life of a Syrian Christian daughter, married for love, walked away from an alcoholic husband, survived debilitating asthma, and with sheer willpower founded a school in Kerala that grew into an institution with a waiting list at birth.

Mary Roy was also the petitioner in a landmark Supreme Court case that struck down the Travancore Christian Succession Act of 1916, securing equal inheritance rights for Syrian Christian women in 1986. It was one of the most significant feminist victories in Indian legal history — and one of Mary Roy’s proudest battles.

Amma vs, Mrs. Roy

Mother Mary Comes to Me refuses to tidy up the contradictions. Mary Roy, who broke free of patriarchal control, could be merciless within her own household. Arundhati recalls the impossibility of separating “Mrs. Roy” the principal from “Amma” the mother. Her brother Lalit was the target of much of their mother’s fury — beaten until rulers broke, called a “chauvinist pig” for small mistakes. Mrs. Roy taught Arundhati about Shakespeare, Kipling and AA Milne. She read to her children the opening passage of Lolita, then called her brother; G Isaac, Humbert Humbert for his gravitation towards comparatively younger women.

Arundhati, meanwhile, was smothered in affection for excelling at school. The absolute spaghetti-like structure of it all distorted her early sense of feminism: how could a woman fighting misogyny outside reproduce cruelty at home?

From lover to leaver

Roy recounts these memories with bracing clarity. She left home at sixteen to study architecture: ‘I left my mother not because I didn’t love her, but in order to be able to continue to love her. Staying there would have made that impossible. Once I left, I didn’t see or speak to her for years. She never looked for me. She never asked me why I left. We both knew… I watched her unleash all of herself — her genius, her eccentricity, her radical kindness, her militant courage, her ruthlessness, her generosity, her cruelty, her head for business, her wild, unpredictable temper — with complete abandon…‘

The memoir dazzles not only in its maternal portraits but also in its treatment of love, desire, and art. Roy pays homage to her ex-lovers with a compassion rare in public writing. She captures what it means to be young and in love — to fuse passion with projects, to fall apart, to rebuild. Her bohemian wanderings as student, product designer, architect, actress, screenplay writer, and eventually novelist all appear here.

What holds the book together is Roy’s unmistakable voice. Even as she writes about her most private relationships, she cannot help but radiate the political urgency that has defined her career. The same woman who as a daughter struggled with her mother’s contradictions is the writer who would later stand against the annihilation of caste, religious majoritarianism, and state violence.

The same woman who as a daughter struggled with her mother’s contradictions is the writer who would later stand against the annihilation of caste, religious majoritarianism, and state violence.

Her prose continues to be as striking as it has ever been. The writing is simple and lyrical — she calls herself her mother’s lung during asthma attacks for fear of death, she mentions an abortion, she speaks about lovers with whom she feels merged in sorrow and the prospects of art. She flits through mentioning the urge of someone coming from a broken home fleeing from safety they may find elsewhere. All to remind the reader that writing is a tender observation, almost forced prayer.

The human condition in Arundhati Roy’s memoir

Many mother-daughter relationships are complex — it is far from an untouched theme in literature. Roy excels at simply exploring the human condition. One can a feminist and cruel, one can be an educator and belittle their own child.

Life runs in absurd extremities and human beings do not take particularly long to swing on either side of the pendulum — and it is all natural. We are morphed into products of the societies we live in, whether we like it or not. Roy’s memoir embraces this uncomfortable truth, and in doing so, it becomes a testament to the contradictions we all carry.

About the author(s)

Treya covers art, culture, climate and the environment. She has aspired to be a journalist ever since she was little. She has reported for The Hindu and Deccan Chronicle among others and explores how feminism takes root in everyday life by leading sessions with young people on gender, digital safety and the "good girl" syndrome.