Employment faces a crisis in the wake of generative AI advancements and a global shift favouring increased automation, where workers are being replaced by artificial intelligence to cut costs and improve efficiency. However, the unchecked growth of AI, without policy frameworks in place to protect workers, threatens to exacerbate economic inequalities and worsen economic outcomes for large sections of the population worldwide. A new UN report highlights just this.

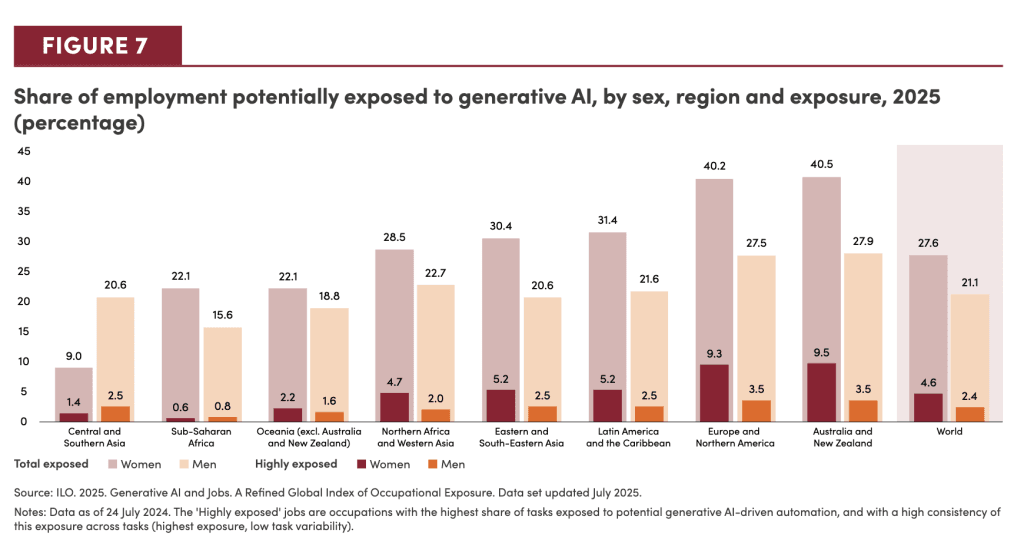

A United Nations report entitled The Gender Snapshot 2025 found that women’s jobs face a greater threat from generative AI than those of men. Globally, 27.6 per cent of jobs held by women face the prospect of potential displacement due to generative AI, while only 21.1 per cent of jobs held by men do. Of these, 4.6 per cent of employment held by women is categorised as ‘highly exposed’ to the threats of AI automation, while the number for men is 2.4 per cent.

Generative AI is a type of artificial intelligence that can create original content, such as text, images, audio, and video. Generative AI poses a threat to jobs by enabling the automation of specific roles, often without requiring significant human intervention or oversight. However, such automation comes with a significantly high risk of displacing jobs, increasing unemployment, exacerbating economic inequalities, and accelerating the economic marginalisation of already high-risk groups.

These figures, however, vary widely across global regions, with some areas experiencing greater disparities between genders and a more pronounced impact on jobs overall. However, women face greater threats in all regions except Central and Southern Asia.

In its assessment of the progress made in achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 8 – Decent Work and Economic Growth – the report noted gains made by some countries in enabling women’s participation in the workforce and reducing barriers to entry, while highlighting the looming threat posed by generative AI to employment and the disproportionately gendered impact of this. To address this, the report recommends investing in digital and technical skills for women, as well as implementing gender-responsive labour and social protection policies, to ensure that women are not left behind.

Regional findings from the report

According to the report, threats from AI automation are more severe for jobs held by both men and women in developed countries, where a large number of jobs are not labour-intensive and can potentially be automated. Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand face the prospect of the highest numbers of jobs being replaced by AI.

Further, the threat to women’s jobs in these regions is significantly higher than the global average. In Europe and North America, 40.2% of jobs held by women are at risk, while in Australia and New Zealand, this figure is at 40.5%. Both these regions also see the highest gender disparities, significantly above the global average and higher than rates in any other area.

Threats from AI automation are more severe for jobs held by both men and women in developed countries, where a large number of jobs are not labour-intensive and can potentially be automated.

In these regions, the proportion of jobs held by women that are categorised as ‘highly exposed’ to AI threats is remarkably higher than that of men categorised similarly. In Europe and North America, the estimated figure is 9.3%, and in Australia and New Zealand, it is 9.5%. At the same time, the number of jobs held by men that are highly exposed to threats from automation in both regions is 3.5%.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, while jobs held by women are estimated to have a greater risk of being automated, the portion of these that is categorised as highly exposed remains slightly lower than that of men at 0.6% and 0.8%, respectively. Further, while the proportion of men’s jobs categorised as highly exposed remains relatively stable across world regions, the share of women’s jobs that are highly exposed to automation sees staggering differences worldwide, ranging from 1.4% in parts of Asia to 9.5% in Australia and New Zealand.

Findings for South and Central Asia

Central and South Asia emerge as the only regions where women’s jobs face fewer threats than those of men. 9.0% of jobs held by women in this region are at risk of being automated by AI, with 1.4% of these being classified as highly exposed. Whereas, for men, these figures stand at 20.6% and 2.5%, respectively.

However, most of these figures are below global averages (except men’s jobs in the highly exposed category, which is nominally higher than average). The share of employment held by women that can be automated is significantly lower than the global average and two to four times lower than in any other world region.

The share of employment held by women that can be automated is significantly lower than the global average and two to four times lower than in any other world region, due to these economies being primarily agrarian.

While on the face of it, these figures might seem encouraging, they don’t indicate that these governments are implementing policies and frameworks to ensure job security and continued employment in the face of rapid AI advancement and increased automation. Nor do they indicate gendered threats relating to automation being prioritised and addressed. Why Central and South Asia emerge as the only regions where women’s jobs are at lower risk can be understood by looking at the nature of these economies.

Data from South Asia indicate that 60-98% of economically active women are engaged in the agricultural sector in these countries. In fact, in many South Asian countries, women make up the majority of the agricultural workforce. A UN Food and Agriculture Organisation report found that in South Asia, 70 per cent of working women are employed in the agrifood sector. In comparison, the global average is only 36%. Agriculture also plays a vital role in the economies of Central Asia. While the degree of women’s engagement in the sector can vary drastically across Central Asian countries, the out-migration of men to urban areas often means that women take on a significant portion of the agricultural responsibilities in the region.

Furthermore, 80% of women not engaged in the agricultural sector are employed as informal labour in South Asia. According to the International Labour Organisation, informal labour exists globally, but it is predominantly found in the Global South. The agrarian and informal nature of South and Central Asian economies, alongside the increased likelihood of women being engaged in unorganised sector activities, explains the low risks estimated for women in this region due to AI automation.

While AI automation can affect all sectors, it predominantly threatens entry-level white-collar jobs. Manual and labour-intensive employment in the agricultural and informal sectors cannot be fully automated with the same ease, or in some cases, at all. Furthermore, the high initial costs associated with automation can also be an insurmountable barrier for many actors in these sectors, especially in the agricultural industry, where land ownership and farming often remain small family enterprises. Therefore, the findings of the UN report reflect these realities.

Other notable findings in the report

Beyond the impact of automation on women’s employment, the report noted that the gender gap in workforce participation narrowed slightly, by two percentage points; however, it stated that significant barriers to economic participation persist. These include pay gaps, limited leadership opportunities, occupational segregation, and unequal caregiving and domestic burden.

Workforce participation of women with young children is said to be the most impacted due to disproportionate care and domestic responsibilities. In 2023, 66 per cent of prime-aged (25 to 54) women who were out of the workforce cited caregiving responsibilities as the reason for non-participation.

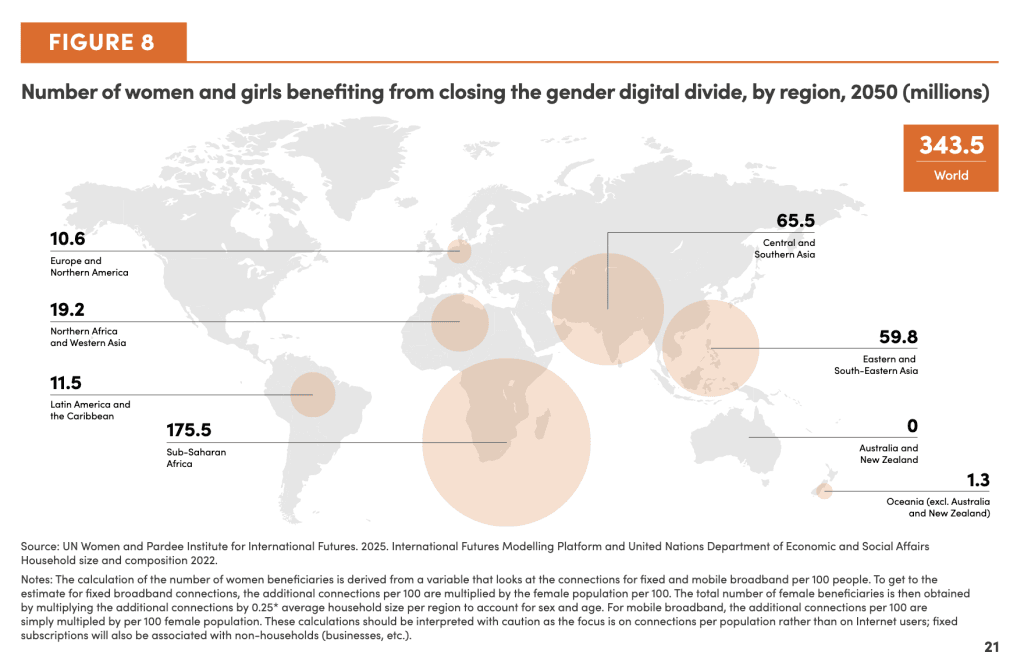

The report also highlighted barriers to women’s benefit from technological advancements. These disparities were found to be worse in low-income countries and among adolescent-aged girls and young women. The report estimates that 343.5 million women worldwide will benefit from closing the gendered digital divide. In Central and Southern Asia, this number stands at 65.5 million, with the highest impact estimated to be in Sub-Saharan Africa, where 175.5 million women are potentially expected to benefit from bridging these gaps.

These findings from the report are of great significance because, in a digitalised future, overlooking the gendered aspects of access to technology and the consequences of digitalisation will widen gender inequalities. Addressing the issues raised in the report is not only essential for ensuring the economic well-being of women but also for promoting social equity, as financial self-sufficiency enables women to achieve greater autonomy by reducing their reliance on patriarchal familial structures for survival.

Furthermore, uniform access to technology and the benefits derived from it are crucial for women’s education, access to information, and public and political participation. In a digitalised world, gender inequality cannot be addressed wholly or meaningfully without remedying digital disparity. Inequality in access to digital tools and literacy will only mean worsening marginalisation and deteriorating outcomes across the board for women.

As AI technology rapidly evolves and automation becomes an inevitable reality, the failure to implement effective policies aimed at ensuring the economic well-being of workers and addressing widening economic inequalities can be catastrophic. However, of those impacted, the most economically marginalised sections of the population, including women, will shoulder the burden of such economic threats disproportionately.

Therefore, policy interventions alone won’t suffice; a gendered approach that takes into account women’s marginalisation and unique vulnerabilities when attempting to mitigate threats from automation is central to meaningful action that protects everyone. Without this, we threaten to further economically marginalise women, who are already one of the most economically marginalised groups across the globe.

About the author(s)