So yes, I’m a vegetarian. No, I’m not going to cook non-vegetarian dishes just because society expects me to or because that’s what it takes to be considered a “good” wife. It’s not because I’m stubborn or don’t care. But because my values also matter. My comfort also matters. My boundaries also matter.

A simple comment has a deep impact

I grew up in a home where eating non-vegetarian food was completely normal. It was normal to celebrate with non-vegetarian food on the plate. But, somewhere, I knew it wasn’t for me. I made a different choice and decided to stay vegetarian, not because someone asked me or by any traditional imposition, but because it felt like the right thing for me. In fact, a plant-based diet became more than food; it actually reflected my values, belief system, and provided a sense of comfort. No one questioned it, and even I never felt the need to explain to somebody. Until one comment from a relative made me stop and think, and forced me to realise that my food choices weren’t just about food anymore. Food choices are also about feminism, identity, and the subtle ways in which everyday beliefs get questioned.

One afternoon, a simple refusal to cook non-vegetarian food and washing those dishes led me to face a comment, ‘That’s fine now, but after marriage, what will you do if your husband loves non-vegetarian food? You have to cook for him. Perhaps you need to wash the utensils as well. So, you have to learn to cook everything, regardless of your preference.‘

At first, I just smiled, not really sure what to say. But later her words stuck with me, it made me angry, and I was frustrated by her words. I took a pause and realised it wasn’t about food but about the expectations. It made me understand this unspoken belief that once a woman gets married, her personal choices somehow take a backseat. Particularly in the kitchen, what matters the most is what the husband wants, even if it means setting aside your own beliefs.

I keep questioning myself and others: why it is automatically assumed that I, as a woman, must compromise my values, which are non-negotiable for me, for someone else’s comfort? Would a man be told to do the same?

Questioning everyday

Though I engaged with feminism through books, discussions, and online spaces, this comment was pivotal in my feminist journey. I always stood against the stereotypes and prejudices that women face. But that moment was personal. It helped me to recognise that feminism is not just about big theories, it’s about everyday choices and the power to make your own decisions.

I started to reflect deeply about how patriarchy is quietly hidden in families, in the name of tradition, or normalised behaviour.

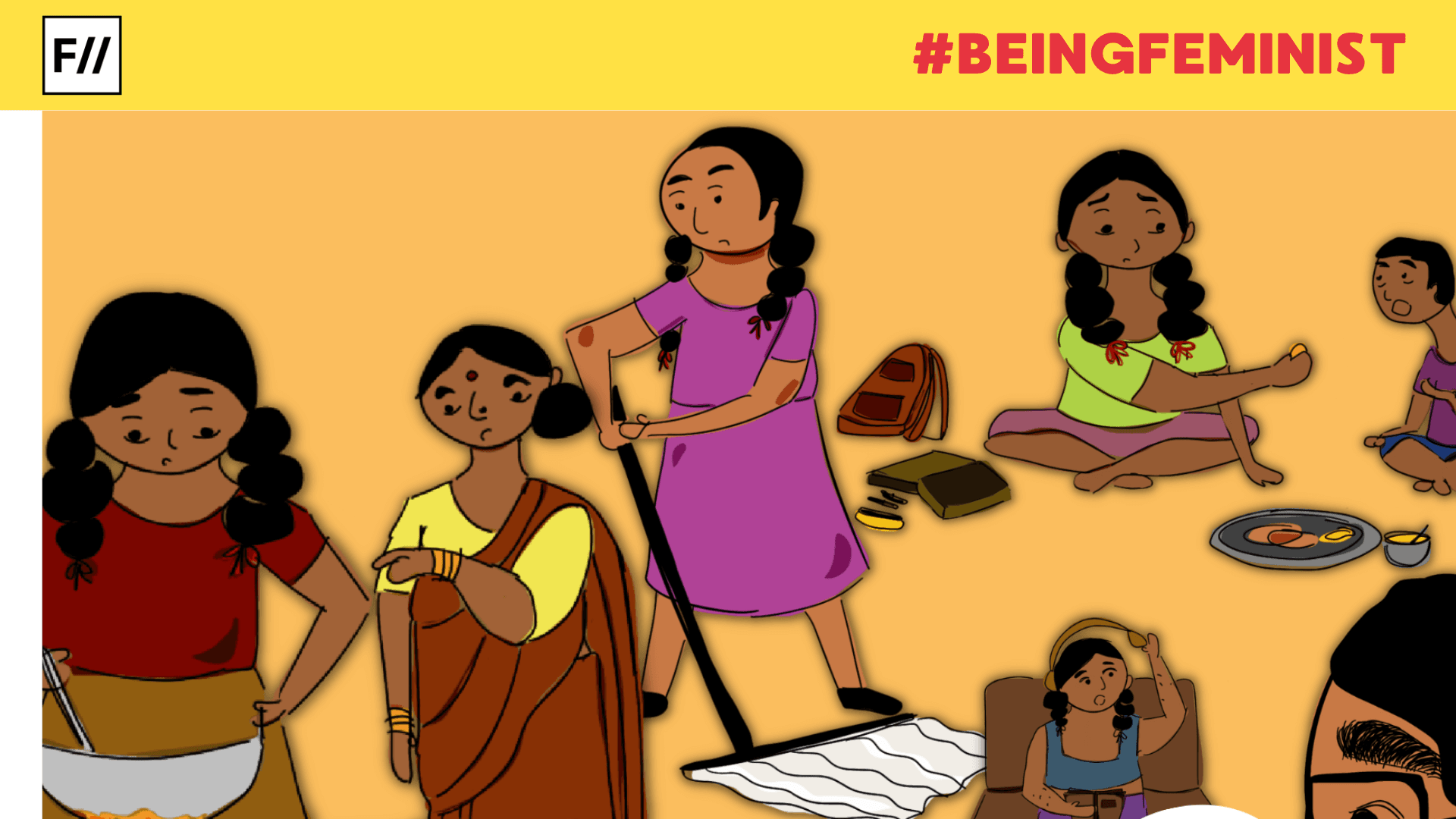

I started to reflect deeply about how patriarchy is quietly hidden in families, in the name of tradition, or normalised behaviour. That comment carried a deep message: women are expected to compromise. Whether it’s putting their career or dreams on hold, dressing a certain way to keep others comfortable, or cooking something you are not comfortable with, all of these make you a good woman in society. In this way, sacrifice is not only accepted; it’s expected.

These incidents and interactions led me to think about why women are always expected to adjust in a relationship. Why does love or marriage have to mean giving up your own identity? Why is cooking something that you don’t feel comfortable with seen as a sign of love or loyalty? And why is cooking also a gender-specific duty?

I’m not against compromise; I believe it’s important in any relationship. But it shouldn’t always be one-sided or based on gender. If I respect someone’s choice to eat non-veg, they should respect my choice as well. It’s that simple.

Culture, control, and cooking

Food is an essential part of culture and identity. And in this way, gender also shapes what is expected from us, especially as women. When someone says, ‘you’ll have to cook non-veg after marriage,’ they’re not just asking about dinner but actually reinforcing centuries-old gender roles; the idea that a woman’s primary job is to serve her husband, no matter what.

What was actually more disturbing was the normalisation of such an opinion. The relative wasn’t being rude or forceful. She truly believed she was giving me helpful advice, which is what makes it more dangerous. These ideas, are passed down as wisdom, when, in fact they are chains that hold us back.

Feminism is not always loud or public. Sometimes, it’s just there, in the quiet, everyday choices we make, in what we wear, how we speak, who we care about, and even in what we choose to cook or not cook.

To be honest, being a feminist in these situations is hard. It’s actually much easier to stay silent or move on. But many times, silence means acceptance. That particular incident made me realise the importance of speaking up, not just on social media or public spaces, but in our homes, among our relatives, and even in conversations that are deemed “too small” but actually matter.

Even small boundaries matter

Feminism is not always loud or public. Sometimes, it’s just there, in the quiet, everyday choices we make, in what we wear, how we speak, who we care about, and even in what we choose to cook or not cook.

For me, being a feminist means protecting my right to say no. It actually means setting boundaries, even if they look small to others, and defending them. It definitely means rejecting the very idea that marriage is a space where women must prove their worth through service.

Everyone’s choices matter, including mine

So yes, I’m a vegetarian. No, I’m not going to cook non-vegetarian dishes just because society expects me to or because that’s what it takes to be considered a “good” wife. It’s not because I’m stubborn or don’t care. But because my values also matter. My comfort also matters. My boundaries also matter.

For me, standing up for myself isn’t about rejecting tradition outright. But it’s important to ask who these ideas, in the name of traditions, actually benefit, and what we lose when we follow them without question. It’s about finding the freedom to live honestly and without apology.

About the author(s)

Himani is a postgraduate in Political Science from Ramjas College, University of Delhi with a keen academic focus on gender, culture and social justice. Her academic and field experience includes research and project coordination in areas such as tribal entrepreneurship, environmental advocacy and community service.