On the third day of her wedding in Jiangyong County in Hunan, China, a bride opened a silk fan. It held poems written by her mother or sisters. The writing did not look like Chinese characters. Instead, the curves were soft and curved that resembled embroidery rather than an ordinary script. The bride read quietly, knowing that no man in the house could understand it. This was Nüshu (女书), meaning women’s script, which is a writing system created and used only by women in Hunan for generations.

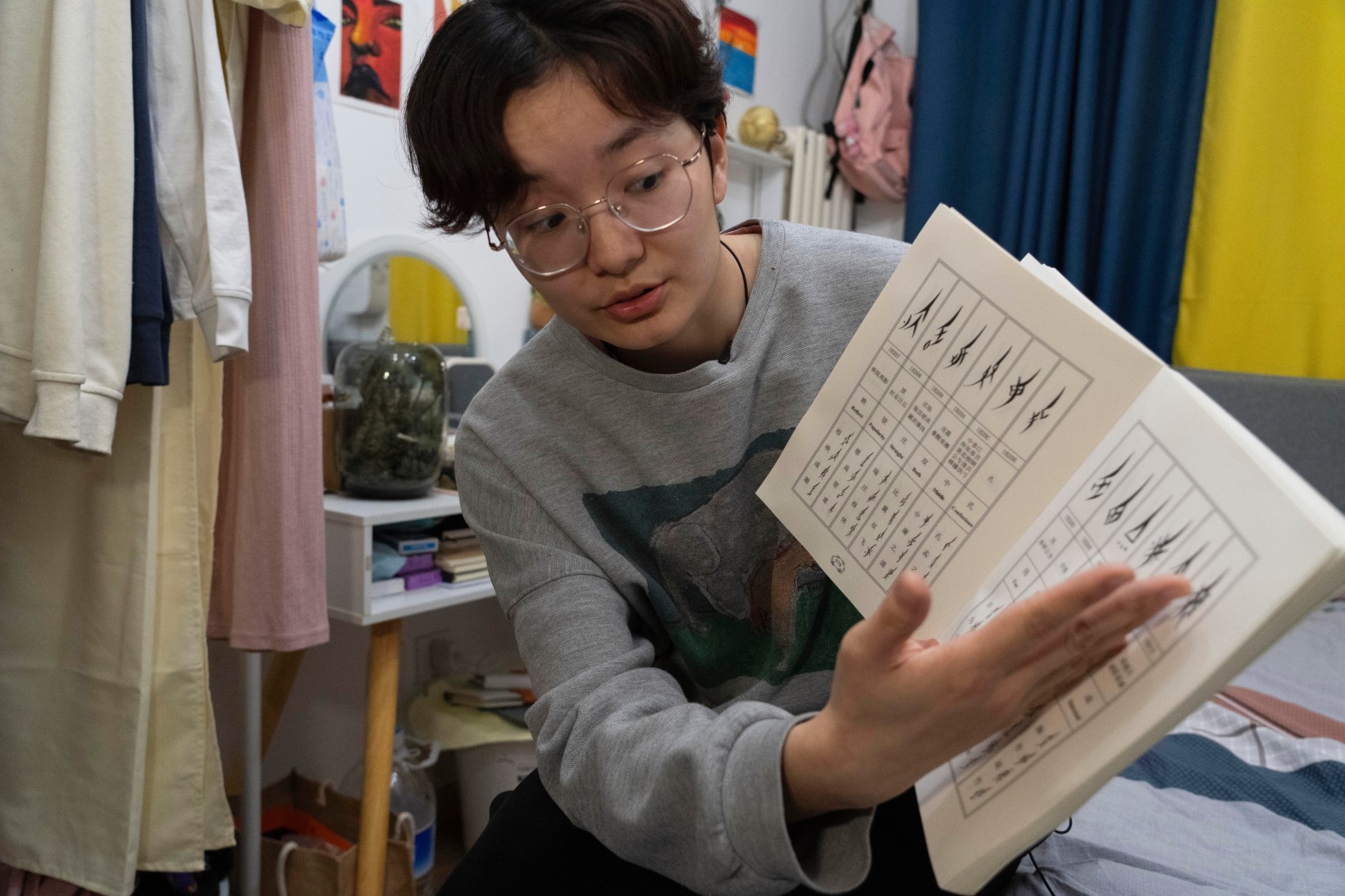

‘Women in ancient days couldn’t get the chance to go to school. So the wise women in Jiangyong created their own language,’ explains Dr. Zhao Liming, a Tsinghua University professor who has studied the script for years.

For women who had left their natal homes, Nüshu was not simply a secret code but a form of connection and survival. In a time when education was reserved for men only, it let women express grief, love, and memory in words men can not control.

What was Nüshu?

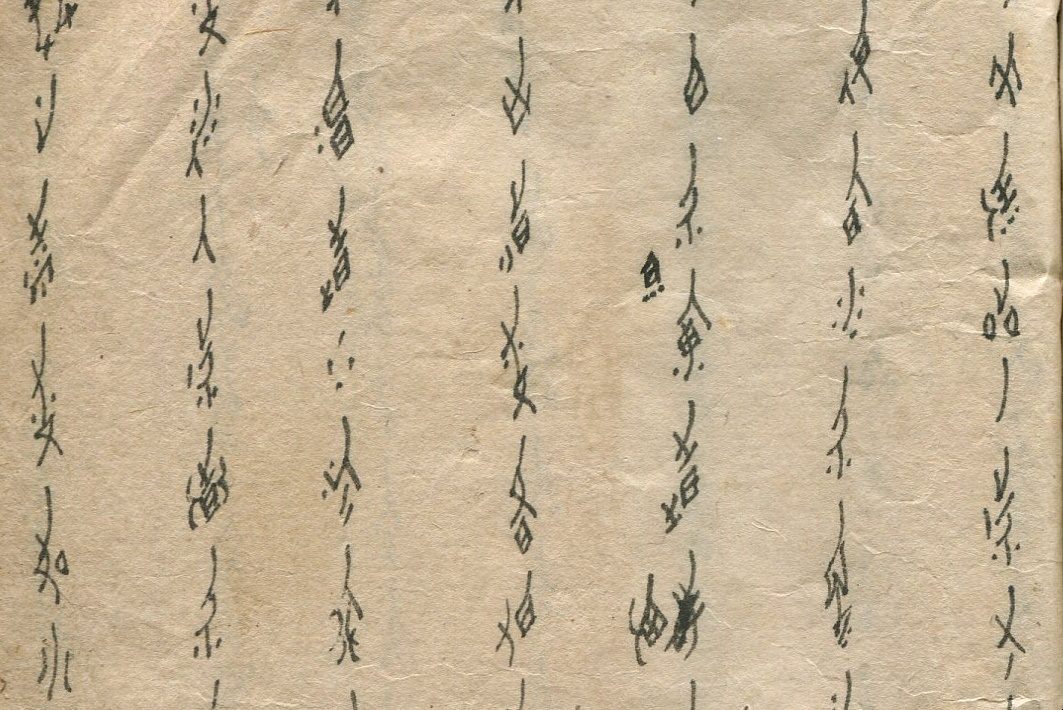

Nüshu did not follow the complex system of Chinese characters. It was a phonetic script of 600-700 characters, with each standing for a syllable. Its strokes are slim and tilted with an appearance of stitched thread rather than standard writing, which is why people ended up calling it “mosquito-shaped”.

Women used Nüshu in several ways, such as writing poems and autobiographies in booklets, exchanging “third day letters” with brides for comfort and advice, and sharing songs and laments through writing on a fan or sewing on textiles.

Women used Nüshu in several ways, such as writing poems and autobiographies in booklets, exchanging “third day letters” with brides for comfort and advice, and sharing songs and laments through writing on a fan or sewing on textiles.

Anthropologist Fei-Wen Liu, who has conducted fieldwork with elderly Nüshu practitioners, expressed, ‘Prior to the Liberation of 1949, Jiangyong women were accustomed to using Nüshu to compose sisterhood letters, wedding literature called sanzhaoshu (‘third-day book’), prayers, biographic laments, folk stories, and other narratives in verse form.’

One preserved excerpt captures this intimate bond of sworn sisterhood: ‘Being sisters of a pair, we can consult with each other when needed, like the birds in the garden, flapping wings or twittering in the same tree together.’

Women’s words in a patriarchal world

Nüshu emerged in a society where women were often denied formal education and were limited to domestic space. In Jiangyong, women were often married young and moved away from their natal families, which left them socially isolated. Here, Nüshu became a source of solidarity for these women. It allowed them to share grief, preserve memories, and maintain bonds across generations. Nüshu served as an archive of voices that were ignored by a male-dominated public sphere.

There are similar echoes in India. In Bengal, women stitched Kantha quilts that depicted stories of love, loss, and everybody’s life, serving as a form to convert private experiences into shared memory. ‘We will work on this at least an hour a day,’ says Kantha artisan Mousammad Sabina Begam of Johari village, Natore. ‘It’s a good way to relax and catch up with the women‘, she added. In Maharashtra, Warli women also painted mud walls with geometric shapes that told stories of their communities and celebrations.

These examples reveal a common pattern where women lacked either access to education or a public platform and turned to alternative forms of expression. These became quiet archives of survival and memory that serve as legacies that scholars and feminists are only now beginning to uncover.

Feminist readings of Nüshu

As Fei-Wen Liu observes, Nüshu encoded experiences and feelings that otherwise might have been silenced. She talks of “third-day books” (San Chao Shu) that were given to brides that carried lessons in empathy and sisterhood. These enabled women to share advice, give comfort, and hope in a world that is shaped by patriarchy.

Comparisons with Indian traditions strengthen this connection, as just like Nüshu, Kantha quilts, and Warli paintings were some ways used by women to pass down memories of birth, marriage, sorrow, and survival.

Comparisons with Indian traditions strengthen this connection, as just like Nüshu, Kantha quilts, and Warli paintings were some ways used by women to pass down memories of birth, marriage, sorrow, and survival. These mediums were not valued initially, similar to Nüshu, as historical or cultural records. These were quiet and invisible archives made by women for women. In modern feminist theory, such “soft” literacies remind us that remembrance and endurance don’t always have to be loud acts of defiance.

Decline and rediscovery

Nüshu began to fade in the early 20th century. After the Communist Revolution in 1949, many women stopped learning Nüshu as public education expanded. During the Cultural Revolution, many texts were lost. Over time, only a handful of women still remembered the script.

Yang Huanyi, who was the last fluent native Nüshu writer, died at the age of 98 in 2004. She told reporters, ‘When I learned Nüshu, it was to meet with friends and sisters to exchange our thoughts and letters. We wrote what was in our hearts, our feelings.’ Her passing marked the end of Nüshu as a living, women-only script. As China Daily reported it at the time, ‘Chinese linguists say her death put an end to a 400-year-old tradition in which women shared their innermost feelings with female friends through a set of codes incomprehensible to men.’

Yet Scholars like Zhao Liming have worked to keep the script alive. She notes, ‘The Nüshu script was everywhere in the local communities. Some were in books. Some were written on folding fans or stitched in clothing.’

Today, Nüshu lives on in the museums of Jiangyong and cultural projects like the 2022 documentary Hidden Letters. Similarly, in India, Kantha quilts and Warli art are being revalued as cultural heritage and appreciated by historians. These revivals show us a feminist effort to bring forward women’s hidden archives into public memory while keeping their personal meaning.

To read Nüshu today is to confront the paradox about women’s history and how so much only survives in fragments, fabrics, and whispers.

To read Nüshu today is to confront the paradox about women’s history and how so much only survives in fragments, fabrics, and whispers. Yet there lies so much power in these forms of quiet resistance and remembering.

Nüshu reminds us that history is not only a record of kings and their wars, but also about mothers and daughters sharing words in silence that the patriarchy created.

Nüshu speaks to Indian feminist struggles, too. Just like Kantha quilts and Warli paintings were dismissed as women’s pastime by the colonial and patriarchal system, Nüshu too became marginalised. Both reveal how women found ways to survive by writing through materials of everyday life: cloth, thread, mud, and silk.

Uma Chakravarti points out that it is important to recover such practices because women’s knowledge systems are erased not only by patriarchy but also by colonial modernity, which ultimately decides what counts as history.

To write in Nüshu was never to seek recognition from men but to leave a mark for other women. A secret. A source of hope.

When the young bride opened her fan and read her mother’s poem, she was not alone. It showed that even in confined spaces, women found space to speak to each other. The whisper carried through the secret script preserved a sisterhood that refused to be erased.

About the author(s)

Juhi Sanduja is an Editorial Intern at Feminism In India (FII). She is passionate about intersectional feminism, with a keen interest in documenting resistance, feminist histories, and questions of identity. She previously interned at the Centre of Policy Research and Governance (CPRG), Delhi, as a Research Intern. Currently studying English Literature and French, she is particularly interested in how feminist thought can inform public policy and drive social change.