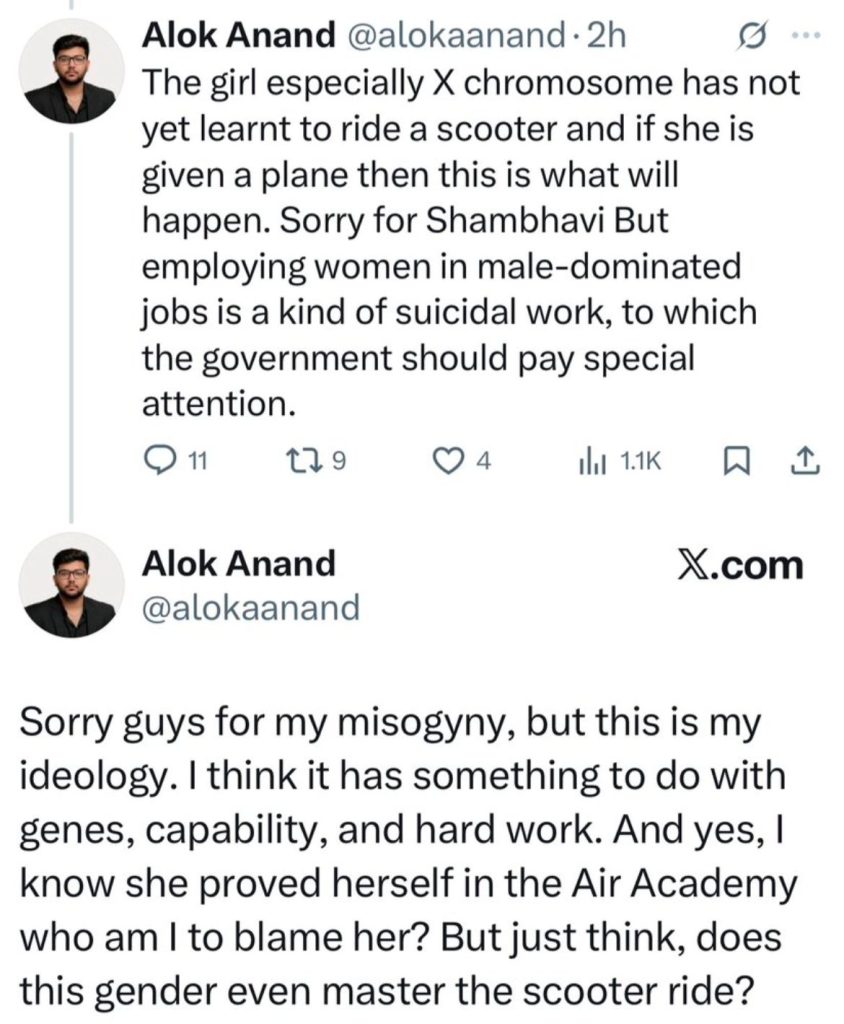

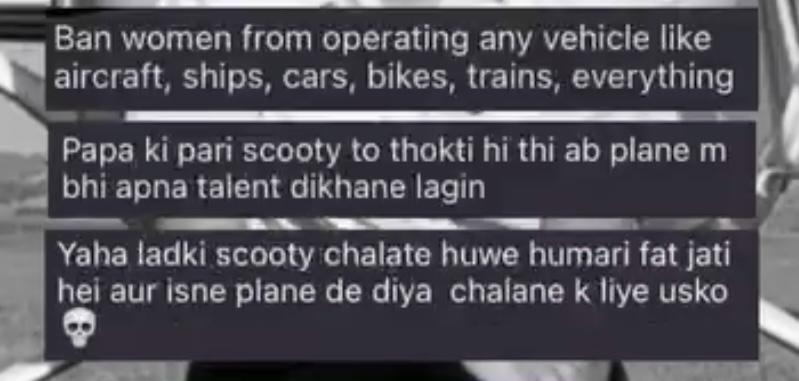

Maharashtra Deputy Chief Minister Ajit Pawar and 4 others, including a twenty-five-year-old First Officer named Captain Shambhavi Pathak, died in an unfortunate plane crash in Baramati, Maharashtra. The immediate aftermath of this tragic incident was a sudden eruption of social media, not just with grief but with something far more sinister, mockery created out of someone’s death. Comments that appeared to be referring to the male and female pilots aboard emerged across social media platforms, transforming a devastating tragedy into an occasion for gendered ridicule.

This response demands interrogation not merely as an isolated act of cruelty, but as a mirror that reflects the face of structural violence against women who dare to claim space in professions that have long been defined by men. The response echoes Khaled Hosseini’s famous line that “A man’s accusing finger always finds a woman,” revealing how gender becomes the quickest explanation when facts are inconvenient.

When Gender Becomes the Only Lens: Epistemological Violence in Action

When a woman pilot dies in a crash, and the immediate response is to invoke her gender as explanation, we witness what Iris Marion Young calls ‘Cultural Imperialism‘ in its rawest form as prejudice framed by dominant sections of the society turns into common sense. Captain Pathak is denied subjecthood as a trained professional with strong credentials as a commercial pilot. Instead, she becomes reducible to a single category, a woman. This cannot be termed as mere mockery, an accidental comment or a casual joke. The memefication might appear harmless at first, but this form of casual misogyny causes serious harm. It should be called out as epistemological violence, sustained by a mindset that routinely devalues women’s knowledge and competence.

Posthumous Erasure: Denying Women the Right to Testify

Women experience testimonial injustice in their everyday lives, as their words are often systematically disregarded simply because of who they are. What followed Captain Pathak’s death goes a few steps further. It is not a matter of merely questioning a woman’s testimony; she is being denied the right to testify at all. This is posthumous erasure. The technical complexities of the crash were quickly pushed aside. The gap was filled by snide jokes, sexist tropes, and familiar insinuations about women’s competence. A skilled professional with years of experience was reduced to a caricature. Her decisions were mocked rather than being examined with the seriousness accorded to male pilots. In death, her career was rewritten through prejudice, as if gender is the only analytical lens available to explain a tragedy. What is at stake here is not merely respect for one woman but the persistent culture that finds it easier to blame women than to put a question mark on its own patriarchal attitude and misogyny.

The Eternal ‘Other’: How Women’s Deaths Reinforce Male Authority

When a woman enters a male-dominated profession, she carves a ‘space of appearance‘ in the public realm where individuals appear as equals, and, through their very presence, these women challenge the entrenched hierarchies prevalent in society. Their presence is celebrated only to the extent of putting up a WhatsApp status described as women’s empowerment. However, sooner or later, the same people begin to find faults in the same women who were earlier seen as harbingers of women’s empowerment.

The mockery that follows their deaths can be understood by extending Achille Mbembe’s concept of necropolitics to gender, exposing how women’s deaths in professional contexts become sites for reasserting male epistemic authority. The female pilot’s death is used to argue that women don’t belong in cockpits, suggesting their entry into these spaces was always premature and suspect. Each instance of mockery after a woman’s professional failure or death makes it increasingly difficult for subsequent women to escape the gravitational pull of gendered expectations.

In Pathak’s death, her gender becomes inextricable from the analysis. This phenomenon reflects what Simone de Beauvoir identified as the fundamental problem of women’s social position: being defined as the eternal ‘Other’ against which the male ‘Self’ establishes meaning. Men in aviation are individuals, while women are representatives of their sex. A male pilot’s crash reflects on him alone, while a female pilot’s crash reflects on all women. This asymmetry isn’t natural but cultivated through continuous discursive reinforcement. This mockery operates through what Judith Butler identifies as “Performative violence”, speech acts that don’t merely describe but simultaneously construct and enforce social hierarchies. Each comment mocking the driving skills of women does not simply reflect existing sexism, but it also produces and reinforces it.

Breaking the Cycle: Moving Beyond Outrage

The way forward requires more than grief or outrage. The need of the hour is a thorough examination of how professional spaces are still constructed as masculine, how women’s failures are seen as complete failures of womanhood, and how even death cannot protect women from being subjected to gendered judgment that men escape. Until we break down the epistemological and discursive structures that allow such mockery, we continue to inflict all women who strive to occupy spaces they have been historically denied.

The young pilot who died in Baramati deserves justice, one that begins with outright refusal of gendered logic that transforms her death into an occasion for misogyny’s reproduction.

About the author(s)

Gunjan Shekhawat is a final-year PhD Candidate at the Centre for Political Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her working thesis is titled, “Becoming Sati: Ritualisation of Violence amongst Rajput Women of Shekhawati Region in Independent India.” She is experienced in ethnographic research, and her research interests include Feminist Theory, Political Anthropology, Political Culture, and Ritual Studies.