I’ve been to India only four times in my life, thrice when I was a flat-chested, wide-eyed child, and once this year. Related below is an incident, fleshed out and added to with the tongue of fiction, that took place when I was walking to a shopping lot in Thrissur, Kerala, relating an abrupt conversation with a couple of old women. I didn’t learn much from that conversation, them having spoken only a few words to me, yet with their wet, shifty eyes and sucking of teeth, I understood that the concept of freedom for women in India, it shouldn’t only be urged into the skulls of young, virile men. That there are so many more types of people who should understand.

Thrissur, 2014

‘She is dangerous that one,’ whispered the ammas and ammais as they strolled down the street, saris held to their noses in a disdain tinted with approval toward the heavy, suffocating smoke from the buses. They had no approval to spare, however, for the girl who walked down the street in shorts, their eyes crinkled against the sun and their hands pressed even more firmly to their faces, as though by breathing in the dust she stirred up behind her, they would catch some of the ‘foreign-ness.’ They hid behind their yellow fabric and their patterned blouse-pieces, their kohl-stained eyes still narrowed at the girl’s swaying, muscular back as she stumbled slightly over a small hole in the road.

“Boyfriend indoo, mole?” An unhealthily gaunt teenager with an afro shouted at her from the cheap Sunny bike he sat on. Do you have a boyfriend, girlie? The ammais stared in horror as the girl turned toward the boy and grinned, and said in an unforgivably British accent, an obvious, sweet dissent, after which she walked on to the mall, leaving the confused boy in her wake to swallow down the saliva that had gathered thickly under his tongue.

“Foreign padiche.” One of the aunties said, indicating her disgust for the foreign educated in the droplets of spit she sprayed as she enunciated her words. “They all go to Amayrica or England for two-three years, and they come back thinking they are white madams.”

“They could study just as well here.” The other auntie affirmed, sitting down in the rickety teashop chair, swaying dangerously. But she was brought up in the red-dusted villages of Thrissur, oh, she could handle any possible failing in balance, she would kick gravitational pull in the balls with the heel of her chappal. “Why they are sending girls there I don’t know, when they could do some fashion design, or if she is smart, medicine.”

“My son is doing medicine.” The first aunty smirked, but the smirk was pulled down at one end by the knowledge that medicine was not the prime choice for boys in India. That was engineering. “These foreign brought up girls all no good, they don’t know how to cook or clean or sweep. What man would want to marry like this? Not my son.”

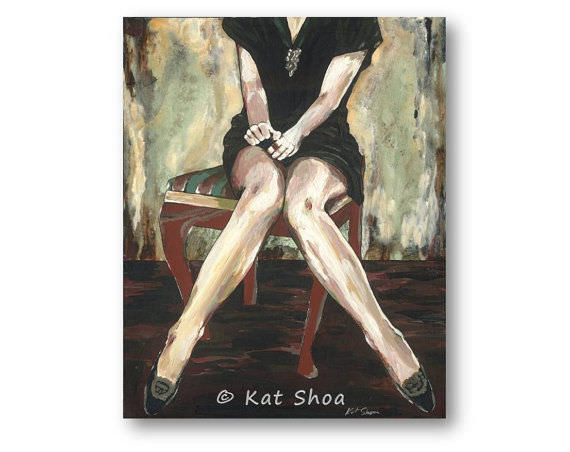

“Eh look, she is coming back.” The second auntie tired of hearing of the other’s offspring’s employment. Her son, after all, was a lowly estate clerk, doomed to a life of terrible monotony, an unattractive wife and a daughter. The girl was indeed coming back, and her well-trained legs flashed nut-brown in their shorts, to some passerby it seemed as vulgar as exposing your cock in public. More so. She smiled at the aunties who sat gaping in horror, as she hailed the tea-stall owner with a wave of the hand (unnecessary, since he was already gaping at her with the intensity of the middle-aged male).

“Oru chai, please. With a chicken cutlet, and beet sauce. Two samosas also.” The girl ordered leisurely, as the owner stared neither at her face nor at her breasts, but at the brown legs she dared to expose to the public. How dare she, he thought with a stirring of sexual arousal – only pale, white, foreign legs should be exposed like this. He nodded solemnly and went in to bark her order at some small boy who would burn his fingers frying the samosas.

“Mole, do you wanting sitting us?” The first auntie gathered up her saris closer to her as though it might make more space on the opposite her. She spoke in the stilted, broken English of someone who had reluctantly passed the ninth standard in school, and stopped there.

“Thank you, auntie.” The girl replied in her unforgivable accent before switching like a tap (not an Indian tap, of course) to crisp, clear-cut Malayalam. “There was no seats here, I’m really grateful you let me sit with you.”

“Wow.” The second auntie’s tone held a begrudging approval of the girl’s native accent. “You speak Malayalam very well. Even for foreign girl like you.”

“Oh, thank you.” The girl smiled, maybe out of politeness, or because her cutlets and samosas had arrived. “How did you know I’m from abroad?”

The aunties didn’t bother with a reply, and only gazed in horror at her shorts.

“But daughter,” said the auntie who had no female children of her own. “You are Indian, no? Why would you go to the country of these Madames and take up a culture that is not yours?”

The Spanish Inquisition had begun.

“Ah.” The girl didn’t seem fazed by the question, and that startled the old women more as they watched her sip her tea steeply and eat a whole cutlet in two bites. This one will eat all the food in the house, thought one, as she stared at the girl’s muscled legs, she obviously ran, or pumped iron –more things that she did that only a man should. The aunties felt a sort of muted horror sizzle in their bones, what if this girl was a lesbian? What if she had sex? They were good aunties, you see, from great families with caste-marks on their foreheads and families stretching back decades, people who owned land (although pretended not to when the Communists reigned), people who closed their legs and looked out demurely behind eyelashes. This girl looked at everything with wide-open eyes and a burning curiosity. No. No, no. Not proper for a good Indian girl.

Forgetting that they had asked a question, the aunties rise and leave.

The girl sits down, and rests her foot on the chair that the fatter aunty had vacated. It was still warm, a tepid heat from the good, obedient Indian backside. The girl smiles, and wished she had her boyfriend with her now, a six-foot white man with pierced eyebrows and tattoos, simply so that somebody would smite him as well as her. But she knows they would look past his tattoos and scars, they would look straight through the stretched holes in his ears and only manage to see the penis dangling between his tattooed legs and the almost unbearable paleness of a skin. For Indians, you must remember, we are a nation who worship our conquerors and despise ourselves – though we say otherwise. The nation that worships the penis, yet shamefully denies the existence of the vagina. The glorious nation, our nation, which locks up a menstruating girl, yet parades a virile, fertile boy, and mother scream in disgust at the sight of menstrual blood on the sheets, yet eagerly search for semen stains on their sons’, as confirmation, he is ready for a girl, my mon, my beta. Which is why the girl, cutlet childishly framing her lips and the grease of samosas on her hand, she is the one who attracts the sneering stares and one old man’s spit that lands merely inches from her unforgivably brown foot.

And why the men passing outside, having stuck their pricks in twenty different, half-unwilling girls – they walk with their heads held high, and tell their mothers about the shameful veshyas that try to force themselves onto them.

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.