This article is part of the #GBVInMedia campaign for the 16 Days Of Activism global campaign to end gender-based violence. #GBVInMedia campaign analysis how different kind of mainstream media (mis)represents/reports gender-based violence and broadens the conversation from violence against women to violence against people from the queer community, caste-based violence and violence against people with disabilities. Join the campaign here.

1. Focus on the crime, not just on the individual

Often the media’s interest in violent crime and sexual assault starts and ends with an individual story or event. Whether it was the Delhi gangrape in December 2012 or the Shakti mills gangrape in August 2013, the media usually focuses all its energies in pursuing a single rape/assault story. As a result, it often misses out on the larger story of rape as a pervasive crime affecting many different women. Use that individual story to tell the wider story about the crime, the justice delivery system, the medical, social and psychological issues.

2. Consider class bias

Much of the time, the Indian media covers gender violence through the lens of class. Crimes committed by and against the middle and upper classes in urban settings get reported more often and in greater detail than those involving poor, rural, tribal, lower caste people. Thus, even the brutal lynching-style murders of four-members of a Dalit family, including two women who were stripped naked, publicly raped and killed, in Khairlanji, Maharashtra in September 2006 received hardly any attention in Mumbai’s English-language press.

Even in the case of crimes against urban working women, while the rape of educated middle-class women, such as the Uber cab case in December 2014 and earlier cases involving women BPO employees, were covered in depth, assaults against working-class women seldom receive that level of attention and when it does, the tone is quite different. For example, within ten days of actor Shiney Ahuja being accused of raping his domestic worker in June 2009, there were articles casually dismissing the crime as an act of passion. “When did a domestic help become a man’s object of fantasy?” asked an article on TOI, quoting an unnamed relationship expert as saying, “…if you observe a maid at work, with ample cleavage on display as she bends to do her work, a man can get enticed” (‘The Maid Trap!’ Times Life, The Sunday Times of India, June 28, 2009).

Similarly, there’s also a visible class bias in the reporting when the alleged perpetrators are men from the lower classes as opposed to men from the middle or elite classes. The tone is more outraged and nasty when the perpetrators are lower class. So consider whether your story is tainted by a class bias.

3. Avoid violation of privacy & identification

Under Indian law (Section 228A), photographs and mentioning any identifying details of a rape survivor is prohibited – this includes name, details of residence, employment, education, and particulars of family members/friends. In short, nothing should be done that compromises the identity of the rape survivor and deters other similar survivors from reporting the crime.

Use pseudonyms instead. You can give a survivor’s age and general background (a student, a working woman) but nothing very specific.

4. Stop harassing survivors and their families

While the law does not allow the media access to rape survivors and their families when a case is ongoing, it’s possible that after a conviction and/or if a victim dies, it may be possible to establish such contact. But do let survivors and their families decide if they want to be interviewed or not, how they wish to be attributed, warn them that their quotes are on the record, quote them in context, and minimise invading a survivor or her family’s privacy or grief.

5. Stop the voyeurism and underhand moralising tone

Do we really need to know about the ‘unnatural sex’ the survivor was subjected to? Or she smoked or drank? Or wore a skirt? Any language, headlines or story angle that suggests that the survivors of sexual violence encouraged the attack on themselves by something they did, wore, went, or said should be avoided. Don’t treat survivors of gender violence as being complicit in the act. Avoid casting aspersions on their moral behaviour and individual character.

6. Don’t only cast public space as dangerous

The media’s growing fascination with sexual violence focuses disproportionately on violence against women in public. Also that violence is covered very differently from violence faced by men. As men are an accepted presence in public space, violence against them is represented generically. But an assault on women always puts the spotlight on their sexual safety – most importantly, no reporter ever suggests of a male survivor, “But what was he doing there?”

By continuously casting public space as more ‘dangerous’, not only does the media deter women from accessing the streets by making their families/communities police them more closely, it also plays down the seriousness of domestic violence which by all statistical accounts is the bigger villain. So follow the crime statistics and show us what they reveal, don’t blindly build your story on perceptions of danger.

7. Change the vocabulary when reporting sexual violence

Language can uplift or impair and in the case of reporting on a sensitive issue like gender violence can cause serious long-lasting damage if used carelessly.

Favour the term ‘survivor’ over ‘victim’ when referring to a person who has been raped – for as gender activists point out the use of the word ‘victim’ reinforces negative stereotypes about women as passive and weak.

Avoid words/phrases that underplay violence or play up gender stereotypessuch as “eve-teasing” or “sex pest”. If you describe the sexual assault, don’t make it sound like lovemaking – “raped” or “penetrated” are more appropriate than “had sex with”. Avoid use of words like “fondled” when meaning “molested”. In fact, any vocabulary that in any way suggests the survivor deserved or enjoyed the assault should be shunned. And keep away from language that can assign blame, such as describing a survivor as being “dressed provocatively.” Use the active voice when reporting crimes related to gender violence as this helps put more specifically the onus of the act on the perpetrator. So, “A 32-year- old man allegedly raped a 23-year-old woman …” is better than “a 23-year-old woman was raped…”

When reporting violence against trans* people or sexual minorities, be cautious how you refer to them. Consulting a gender activist may be a good idea. Laxmi Murthy in her most insightful chapter ‘Women, Men and the Emerging Other’ in Kalpana Sharma’s edited volume, ‘Missing Half the Story: Journalism as if Gender Matters’ (Zubaan Books, 2010), offers a helpful understanding of how to report on trans* people and sexual minorities. Use the term ‘transgender’ as an adjective not as a noun, she suggests. So say ‘a transgender person’ not ‘a transgender’. Avoid ‘hermaphrodite’, instead use ‘intersex person’ to describe a person whose biological sex is indeterminate at birth. And do ask trans* people which pronoun they would like you to use when describing them.

8. Never trust single-source stories

Try to get a variety of sources or get the information provided by one source, even if it is the police, substantiated in other ways. At the very least present the information in a manner that the reader/viewer knows that not all of it is completely substantiated and that it is only one version.

9. Balance the survivor and suspect’s version

Don’t tell us all the gory details of the survivor’s life – including the number of men she regularly texted – and keep the suspect’s life confidential. Always think how you can balance out the story without doing a disservice to the larger story.

10. Interview the right expert sources

This means that not just anyone who works on ‘women?s rights’ is qualified to comment on a case of gender violence. Locate the right medical, forensic, legal, psychological experts.

11. Provide context to stories

Stories of sexual crime should be set in a context that will inform the public of the reality of the crime and help people protect themselves. Journalists need to provide historical and statistical context to crimes against women and place individual cases in the context of patterns of sexual crimes in the city/nation.

12. Link the specific instance to larger issues

The killing of a newly married inter-caste couple or so-called ‘honour’ killing, for example, opens the door for articles that can raise larger questions relating to caste, patriarchy, traditions and law. Provide linkages to other related issues of gender violence and tell a more broad-based story.

13. Undertake more follow?up stories

Follow up a reported rape/molestation story by highlighting other similar cases, following the investigative and legal process, the psychological and long-term trauma or the social costs of such violence.

14. Policy guidelines and skill training

Ideally news organisation should provide clear ethical policy guidelines with regard to coverage of sexual assault and rape crimes. Regular training workshops should be organised for journalists to upgrade their skills with regard to gender-based violence from legal, medical and social points of view and discuss the ethical dilemmas whilst covering such crimes.

15. Keep track ofuseful online resources

DART Centre for Journalism and Trauma is an ideal online resource for journalists who cover violence providing guidelines and online learning on journalism/photography and trauma. Poynter: a global leader in journlaism is another good resource.

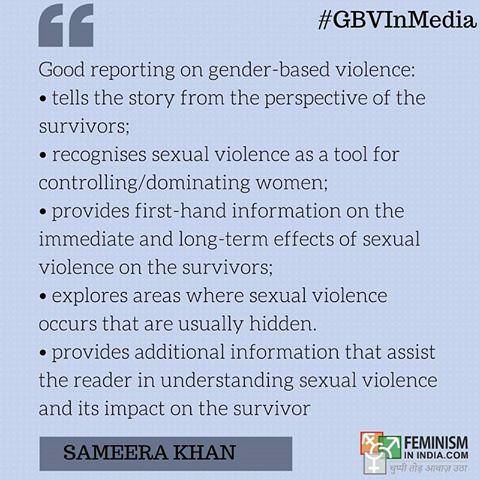

16. Finally, remember that good reporting on sexual gender-based violence

• tells the story from the perspective of the survivors of sexual violence;

• recognises sexual violence as a tool for controlling/dominating women;

• provides first-hand information on the immediate and long-term effects of sexual violence on the survivors;

• explores areas where sexual violence occurs that are usually hidden;

• provides additional information that assist the reader in understanding sexual violence and its impact on the survivor (Ref: ‘Reporting Gender-based Violence: A Handbook for Journalists’, publ. Inter Press Service IPS-Africa, 2009).

References:

i. Five Simple Rules for Reporting on Gender-based Violence, Prajnya

ii. A Guide for Journalists Who Report On Crime And Crime Victims, Justice Solutions

Featured Image Credit: Whomakesthenews.org