Recent news reports suggest that a video that which went viral of a ‘drunk cop on a Delhi metro’, was actually misleading, and an inquiry has revealed that the policeman in question was actually experiencing a stroke, at the time. The policeman is seeking compensation from the Delhi Police, Delhi Metro Rail Corporation, and the Press Council of India, for the damage to his reputation which also led to his suspension, despite the fact that he had been pleading a medical condition. A subsequent inquiry, news reports indicate, which revealed that he was experiencing a stroke have led to him being reinstated in his job.

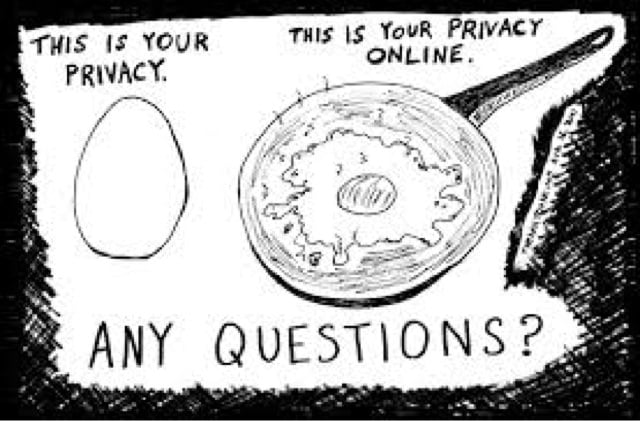

This incident is not isolated, and the phenomenon of ‘things going viral’ can ensure that embarrassing details and information about a person can continue to haunt them for the rest of their lives. Perhaps this is an inevitable consequence of the rise of the social media, the flip side to its numerous benefits. This incident, however, raises larger questions on the impact the social media, search engines, and things going ‘viral’ can have on the reputation, dignity and privacy of people.

A person, who unwittingly, or inadvertently, becomes a meme or a phenomenon on the internet, has to live with it for the rest of his or her days.

The ‘right to be forgotten’, a concept that has originated in the European Union, is important in this context. The right takes roots in the idea that individuals have the right to fashion the course of their lives, and should not be forced to be perpetually stigmatized due to their actions in the past. The ‘right to be forgotten’ basically means that individuals have the right under, certain conditions, to ask search engines to remove personal information about them. The obligation of search engines to remove ‘inaccurate, inadequate, irrelevant or excessive’ information, was laid down in a ruling of the European Court of Justice, in May 2014. The ruling does consider the ‘role played by the Data Subject in Public Life’, and the ‘interest of the public in having that information’ to be important factors that need to be weighed, before deciding on the take down.

Note that this ‘right to be forgotten’ should not be confused as completely overlapping with right to privacy. These are two conceptually different, though overlapping ideas. Privacy, broadly understood, which deals with information that ought not to be in the public domain, but has found its way there. Take the example of ‘revenge pornography’ which involves the release of private information in the public domain, violating the privacy rights of the victims (and its continuance on search engines violates their right to be forgotten as well). However, the right to be forgotten also operates with regard to information that may be legitimately in the public domain, but has now become irrelevant or gives an inaccurate picture. An example of this would be the conviction of an individual over two decades ago, for which the individual has served his prison sentence. The advocates of the right to be forgotten would state that this individual should not be stigmatized by an action/event which happened decades ago. Since the search engine results would be accessible to all his or her potential employers, co-workers, it would curtail his or her right to live as a rehabilitated member of society.

The articulation of this right has evoked strong opposition in countries like the United States, and from entities like Google, and the criticism was that such a right has an adverse impact over freedom of expression, the free flow of information as well as being impractical. There is a real danger, critics say, of a censored internet, if partial information about people is furnished on search engines, as a result of requests from people to take down information about them. It is also true that various countries and contexts place different degree of premium on rights such as freedom of expression and the right to privacy or the right to a reputation. It is, however, important to note that freedom of speech and the ‘right to be forgotten’, need not be seen as being at loggerheads with each other, but can in fact be applied in a harmonious manner.

Glimpses of the application of a similar principle can be found in the Information Technology (Intermediaries guidelines) Rules, 2011. A reading of the Rule 3(2) shows that intermediaries are under an obligation to inform the users of the computer resource to not host, display, upload, modify, publish, transmit, update or share information which could be ‘grossly harmful, harassing, blasphemous, defamatory, obscene, pornographic, paedophilic, libellous, invasive of another’s privacy, hateful, racially or ethnically objectionable, disparaging, relating or encouraging money laundering or gambling, or otherwise unlawful in any manner whatever’.

Further sub-section (4) of these Rules makes it clear that when the intermediary obtains knowledge of information mentioned in sub-rule (2), or the same is brought to their knowledge by what is described as an ‘affected person’, the intermediary is required to act to disable the said information.

An intermediary, has been defined in the Information Technology Act, as ‘any person who on behalf of another person receives, stores or transmits that message or provides any service with respect to that message’, and this includes search engines such as google. Section 79 of the Information Technologies Act deals with the liability of intermediaries, and should be read with the Information Technology (Intermediaries guidelines) Rules, 2011.

This list is extremely broad, and while some terms such as ‘defamatory’ or ‘paedophilic’ are clear, terms like ‘invasive of another’s privacy’ ‘disparaging’, ‘obscene’ and ‘grossly harmful’ are open to interpretation. Commentators have described these provisions as being broader and vaguer than the standard laid down in the right to forget ruling for the take down on online content.

In India, given the prevailing concerns about freedom of expression, perhaps the application of the concept of the ‘right to be forgotten’ in terms that are broad in their ambit will have potential for misuse. There is a tendency, quite understandably to err on the side of freedom of expression. That being said the right of a person to live his or her life unhindered by the stigma of past actions should have some application in the Indian context in limited cases. What the limited cases could be, is up for public debate.

It could include instances where the information is inaccurate (such as in the case of the police official branded as ‘drunk cop’ who turned out to be experiencing a stroke), or in cases where the information about a convicted offender would interfere with their right to live life as a rehabilitated member of society. In the Indian context there needs to be greater specificity in the articulation and crystallization of such a right, if it is to happen at all. While we are on our way to find the best way to balance people’s privacy, the right to be forgotten, and freedom of expression, there is a real need for responsible use of the social media and responsible reporting by media houses.

Disclaimer: This post was earlier published on author’s blog here.

About the author(s)

Srishti Agnihotri regularly appears in Trial Courts, the Delhi High Court and the Supreme Court of India. She is involved in research and advocacy on women's rights and child rights. She completed her Masters in International Human Rights Law from the University of Notre Dame, USA.