“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.” (Article 1, Universal Declaration on Human Rights)

The world is still trying to figure out how cultural patterns interact with universal human rights. These issues come up again and again, while discussing the right of women to enter temples or other places of religious worship, the exemption to marital rape in criminal law (for which cultural justifications are given), the question of women’s access to abortion and contraception, wearing religious symbols (such as the burqa), and of course in rituals that may cause violence to women’s bodies (genital cutting or mutilation).

To begin at the beginning, we need to ask ourselves, what are universal human rights? Human Rights are inalienable rights that are possessed by all human beings. This means that all people, everywhere are entitled to these rights, irrespective of what culture or society they are a part of. Although this universality is a basic principle of human rights law, it has received pushback from cultural relativists.

Cultural relativism is the idea that everything a person does is supposed to be understood relative to their cultural context. It warns us that our actions and preferences should not be seen to be coming from a purely objective standard. In the human rights context, cultural relativism, pushes back on this concept of universality of human rights, and says that some cultural variations to rights are legitimately exempt from criticism by outsiders . Closely allied is the idea that the rights we understand today to be ‘Universal’ are really Western Constructs, and thus should not be used to judge norms and practices in other countries.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DmEuPHiqhZY

From the wider human rights community, cultural relativism has received a pushback because of two possibly worrying consequences envisaged as a result of cultural relativism:

- That a relativist position could end up approving of practices such as head hunting, female genital mutilation, subordination of women and minorities.

- The relativistic position will undermine the human rights movement, which is based on the idea that rights are inalienable and enjoyed by everyone by virtue of being human.

Dominant feminist discourses have opposed cultural relativism, as they fear that arguments of cultural specificity are often, invoked to perpetuate the subordination of women. But this view ignores that women also are also a product of their culture and that their identities as women often overlap with their identities as a member of a cultural group.

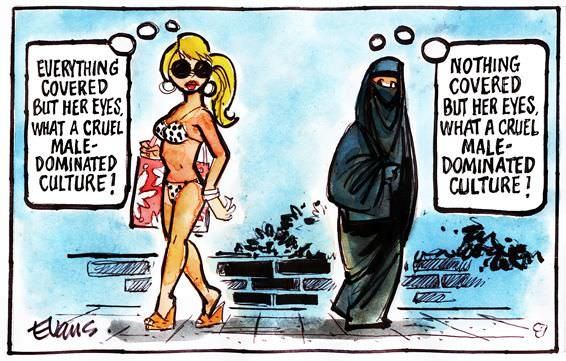

In doing so, such a view may ignore the claims of intersectionality. As can be seen in the course of the controversy surrounding the ‘burkini ban’, women’s identities overlap with their religious identities. An attempt to impose one definition of ‘good morals and secularism’ with the subtext that ‘oppressed’ Muslim women need to be ‘liberated’, is an imperialistic and coercive attempt to control the bodies of women. Ignoring that Muslim women are as Muslim as they are women, and will look at life from both these prisms does not help anyone. It is possible that some Muslim women will see a particular mode of dress as an article of faith and necessary for their religious and/ or cultural expression. The agency argument, on which the larger body of feminists have criticized the ‘burkini ban’, is different from the argument on overlapping identities, though the two together make a persuasive case against a ban of such a nature.

We see that there is some tension between universality claims and claims of cultural relativism. There are well founded fears on the impact an acceptance of cultural relativism will have on women’s rights, there are also adverse consequences of being blind to cultural practices and contexts.

Pluralism/ Cultural awareness/ Intersectionality as an alternative to relativism

Even those who accept that rights are universal understand that awareness of cultural differences is important. In doing so, it is possible to recognize cultural patterns and differences, and yet not allow for relativism (which would refuse to take a position on harmful cultural practices).

This is a pluralistic understanding of rights, that respects the right of those with different conceptions of a right, to be heard. This means that one, as a potential critic of a particular cultural practice one may be aware of one’s biases and cultural moorings, the validity of the other person’s views given their enculturation, and still criticize something as being wrong, if it violates women’s agency, bodily integrity or safety.

Relativism takes the view that certain cultural practices are exempt from outside criticism, and in this it enters murky territory, because such relativism could easily become the plank of which harmful practices are propped up.

For example, those who refuse to decriminalize consensual non-heteronormative sex between, use the excuse of ‘indian morals and culture’ to justify their position. In doing this, they also forget that Indian culture is not static, does not fit in a singular narrative, is not a monolith, and it cannot be used as a justification for violating people’s right to privacy, equality and dignity.

Agency and autonomy are governing principles

A key principle that should help us in deciding whether to criticize a particular cultural norm, is whether it violates women’s agency and autonomy.

This can be a good way to arrive at social or legal arrangements that give room for cultural expression, while ensuring women’s human rights are not violated. Cultural practices are benign if freely undertaken, without the coercive influence of the state, society and family.

Further, creating spaces and structures that allow women to opt out of cultural and religious practices that they do not wish to be a part of, respects the demands of universal human rights, while not being tone deaf culturally.

Who is speaking is as important as what is being said

It is important to note, even when looking at cultural arguments, that who is speaking is as important as what is being said. Is it a representative of the State saying that an exemption to marital rape under a criminal law cannot be removed because Indian Cultural Realities would not permit it?

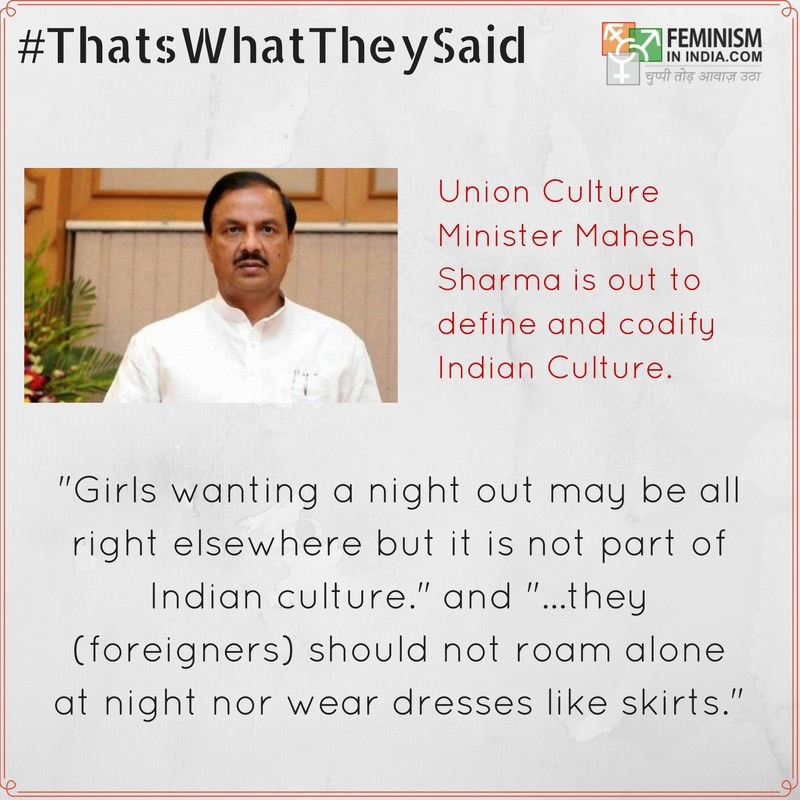

In this context let us look at the comments of Shri Mahesh Sharma, the Tourism and Culture Minister, who advised foreign tourists to not wear skirts, ‘for their own safety’ following it up with the comment that ‘Indian culture is different from western culture’.

This statement shows culture as a justification for controlling women’s bodies, but also highlights a deeper problem. It is emblematic of the State abdicating its responsibility to create safe spaces for women, who do not conform to culturally permissive behaviour.

Cultural arguments should be taken with a pinch of salt if advocated by someone who benefits from the Status quo (religious heads seeking to curtail women’s access to religious spaces such as temples and dargahs). Paying attention to vested interests in putting forward a cultural argument helps a potential critic of a cultural practice in deciding which arguments to take seriously. It is also useful to remember that just like culture, a human rights agenda may also selectively used by the state or individuals to promote an insidious agenda, such as that of Islamophobia. An example of this would be how the rights of Muslim women have been used to promote the idea of a Uniform Civil Code, by the Hindu Right. The loud advocacy of the Uniform Civil Code by right wing groups has polarized the discussion and ignores Muslim Women’s own voices in reforming Muslim Personal Law and their advocacy against harmful cultural practices like Triple Talaq.

Keeping the channels of conversation open

I remember a friend telling me once, ‘being a pro-life feminist, is like being between a rock and a hard place’.

When we ignore people’s cultural moorings and aspirations, the conversations we have with them can become tone deaf. We may end up creating images in our minds of the ‘oppressed’ other, waiting to be rescued, and ignore their voices and agency.

Alternatively, we may end up ignoring that a woman’s identity is not a monolith. Her identities overlap, such as religious affiliation, income, caste identity, race overlap, and a conversation that does not recognize this, is much poorer for it.

Relativism tells us that culture gets a free pass without questions. Pluralism tells us to be aware, respectful and informed by culture, in the implementation of universal human rights.

References and further readings:

1. Donnelly, Jack. “Cultural Relativism and Universal Human Rights.” Human Rights Quarterly 6, no. 4 (1984): 400-19.

2. Renteln, Alison Dundes. “The Unanswered Challenge of Relativism and the Consequences for Human Rights.” Human Rights Quarterly 7, no. 4 (1985): 514-40.

3. Theorizing Women’s Cultural Diversity in Feminist International Human Rights Strategies, Annie Bunting, Journal of Law and Society, Vol. 20, No. 1, Feminist Theory and Legal Strategy.

4. Choudhury, Cyra Akila. “Beyond Culture: Human Rights Universalisms versus Religious and Cultural Relativism in the Activism for Gender Justice.” Social Science Research Network. Retrieved on September 1, 2016.

About the author(s)

Srishti Agnihotri regularly appears in Trial Courts, the Delhi High Court and the Supreme Court of India. She is involved in research and advocacy on women's rights and child rights. She completed her Masters in International Human Rights Law from the University of Notre Dame, USA.

Very aptly written. Much similar thinking is required by all concerned agencies.

I commented that this is an “apt analysis ” and got rebuked by a boy named Gaurav Pawar, right under this fb column. As a progressive community, we got to nip them from the bud itself. My appreciation for putting up this insightful and relevant article