Ismat Chughtai is today regarded as one of the stalwarts of Urdu writing, but back in her heydays, she was considered nothing short of a rebel, an iconoclast. The reason?

Her fiery feminist politics, which reflected itself in every single word she wrote. Chughtai’s seminal short story, the Lihaaf, or the Quilt, catapulted the writer into fame and notoriety, and she faced a lifetime of persecution for her brave exploration of lesbianism and homosexual desires in the story, but it also cemented firmly her reputation as one of the finest writers in literature. Today, Chughtai is remembered fondly by feminists and literature aficionados alike, and, for a reason. Let’s take a glimpse at the life of this extraordinary woman, who refused to do the society’s bidding, and remained till the very end a fierce equal rights advocate and a stellar writer, whose spectacular prose is nothing short of sheer literary magic.

Early Life

Chughtai was born on the 15th of August, 1915 in what is today Badayun in Uttar Pradesh, but spent a majority of her adolescence in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, where her father served as a civil servant. Chughtai belonged to a huge family – she was the ninth of ten children, four sisters and six brothers. Of all her siblings, however, Ismat shared an especially close relationship with her brother, Mirza Azim Beg Chughtai, whom she credits as her earliest mentor and guide. Mirza Azim was himself a famous writer by the time, and could be perhaps credited with shaping Ismat’s literary pursuits. After pursuing a brief stint as a teacher at a girls’ school in Bareilly, Chughtai obtained her degree from the Women’s College at the Aligarh Muslim University. Chughtai was also an active member of the Progressive Writers’ Association, and later became an important icon of the progressive writers’ movement, a significant movement in the history of Indian writing.

Chughtai enjoyed a close, warm friendship with Saadat Hasan Manto, another one of Urdu’s finest writers. Manto too, through the medium of his many short stories, wrote on caste, gender and inequality in many spheres of Indian life. In fact, the two were arrested on the same day for the same reason: obscenity. For Chughtai, it was Lihaaf, and for Manto, it was his seminal story, Bu. Although Manto’s descriptions were far more graphic in nature, it was Chughtai who was held up to ridicule and scorn.

She soon went on to obtain a B.Ed degree after her Bachelor of Arts, which made her the first Indian Muslim woman to hold both degrees. Chughtai married filmmaker and director Shahid Latif in 1941, and the couple collaborated on several films together. She is the screenwriter behind several of Latif’s films, and thus proved that she is as adept at writing for films as she is for books and short stories.

She was born and raised in a large Muslim household, where religious liberalism was the order of the day. Chughtai’s own children went on to marry Hindus, and her opinions on religious ideologies run through many of her stories. Despite being a Muslim, Chughtai was, according to her last wishes, cremated instead of being buried.

‘Lihaaf’ and the start of a literary career

Her first story, Lihaaf, earned the young writer a fan following, while also outraging and disgusting the more conservative members of the society. Lihaaf was first published in the Adab-i-Latif, a literary magazine originating from Lahore.

When Chughtai wrote Lihaaf, she admitted to not knowing much about lesbianism and female homosexual desires. She said, “When I wrote Lihaaf, this thing [lesbianism] was not discussed openly. We girls used to talk about it and we knew there was something like it, but we didn’t know the whole truth…”

In the initial days after the publication of Lihaaf, it was largely presumed that the author of the short story was a man, since Chughtai had not disclosed her real name. When it was discovered that Chughtai was indeed the infamous writer behind Lihaaf, she was charged with obscenity by the erstwhile British government. Chughtai fought for four long, tedious years before she was cleared of all charges.

Apart from Lihaaf, the author also wrote another novel, Ziddi (the Stubborn One), which is also rich with feminist undertones. Chughtai has also authored a number of short story collections: Chhui Mui, Kaliyan (Buds) and Chotan (Wounds), and the Crooked Line. Although no work of Chughtai has been as frequently dissected, discussed and deliberated as the Lihaaf, it goes without saying that every single work of Chughtai, whether novel or short story, carries a mark of Chughtai’s excellence as a writer. As a fierce feminist and staunch supporter of equal rights, Chughtai’s words ring loud and clear with the sound of her demand for equality.

When Chughtai started writing, Urdu literature was, at the time, a reflection of the conservative mindset of the Urdu-speaking populace, where topics like homosexuality did not make for ideal dinner table conversation. She had no desire, however, to play it nice and safe. Her works, be it her novels or her short stories, are all beautiful portrayals of femininity at its rawest, most honest, and are all tinged with defiance and a demand for progress and equality.

Lihaaf has been adapted on film and stage to no end, but the greatest adaptation was undoubtedly Deepa Mehta’s 1996 hit film, Fire, which portrays the lives of Sita and Radha, who, after being ignored by their husbands, develop an intimate, passionate relationship. Based loosely on Chughtai’s short story, the film stars Shabana Azmi and Nandita Das in the leading roles.

Contribution to Feminism

Lihaaf, of course, is the first story which springs to mind when we think of Ismat Chughtai. Chughtai’s short story helped bring female homosexuality out of the closet, so to speak, and in doing so, she quickly became one of the forerunners of the erstwhile latent Indian feminist movement. Another short story by Chughtai, named Gharwali (the Homemaker), is also a reflection of the writer’s feminist ideology. Gharwali, written as a biting satire on the general patriarchal notion of marriage being an essential part of a woman’s life, chronicles the story of Lajjo, an orphan, who, realising that her body is her biggest asset, propositions herself for money. The most significant aspect of Gharwali is not only the extremely humane treatment of sex work, but also the discourse about female sexuality. Lajjo enjoys sex immensely, and she has no qualms about it. Soon, Lajjo is tied down in a dull marriage with Mirza, the master of the house, and finding monogamy incredibly dull and restrictive, embarks on affairs with other men. Mirza soon finds out, and after beating her up, turns her out of the house. The two, however, soon become aware of how much they need and depend upon each other, and get back together, this time without wedlock.

Through Gharwali, Chughtai channels her opinion on how restrictive marriage is for women and the essence of female sexuality, and what a heavy burden marriage is on the head of women. She also writes freely and honestly about female sexual agency, something that has been denied to women for so long. Another telling feature of the story, as stated above as well, is the incredibly normalized description of sex work. Since time immemorial, adulteresses and sex workers have been portrayed by authors and filmmakers as corrupt and depraved and immoral, women whose morality and goodness is somehow shaped and influenced by their sexual prowess.

Chughtai, by writing the story of a young sex worker, shows us that people in the sex industry are humans, like you and me. Lajjo is feisty, with a sharp wit and a quick tongue, who does not and will not adhere to the adage of ‘women should be seen and not hear.’ She makes no secret about how much she enjoys sex, and is scathingly honest about her desires and sexual appetite.

Literary Repute and Fame

Of her indisputable literary talent and skills on paper, Krishna Chander, an eminent writer, says the following words:

… her (Chughtai’s) afsaana makes us think of … a horse race … [there is] swiftness, movement, speed, alacrity … the asana appear to be running … the sentences, symbols and metaphors, voices and characters and emotions and feelings … springing and moving forward with the speed of a storm…”

Naseeruddin Shah, one of India’s most celebrated actor and director, in a memoir written about his acquaintance with Chughtai, eulogizes the great writer by saying,

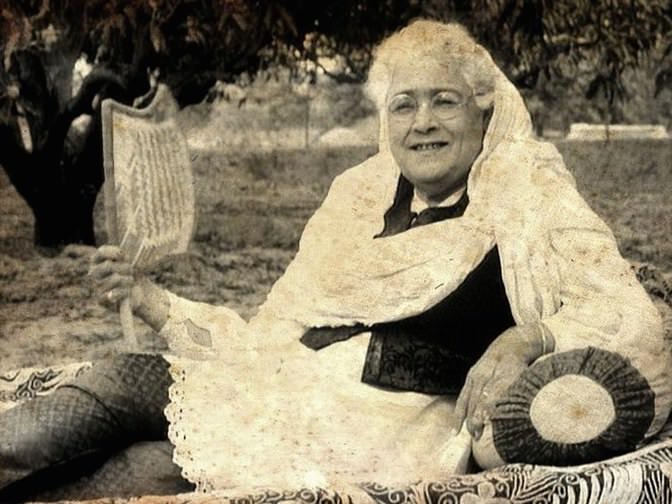

Today after so many years, we are slowly beginning to understand the true meaning of her words. Even after she’s gone, her stories are a source of comfort to us. She had her share of ups and downs and tragedies. She was taunted, reviled, called names, people wrote obscene letters to her, she got death threats, she was hauled to court, but she kept her chin up, and continued to look at the world with love and affection.

There is no doubt that Chughtai’s fearless writing and her exploration of themes that are generally swept under the carpet in India, makes her one of the finest writers to have ever walked the face of this earth.

About the author(s)

Senior student of English at the University of Delhi. I hope you like feminist rants because that's kind of my thing.