Discourses of identity politics and minority rights are often peppered with the words ‘privilege’ and ‘oppression.’ So what does privilege really mean?

Privilege is defined as a set of unearned advantages, enjoyed by those who do not suffer from a particular oppression, simply by virtue of belonging to a specific social or biological group. Privileges are often the hardest to see by those who carry them due to these privileges being normalised by society. The fact that not everybody has these privileges is often forgotten, or ignored.

Also Read: Deconstructing Privilege: Equality, Equity & Justice

Oppression, on the other hand, is much easier noticed than privilege, at least by the oppressed. This is because the oppressed are constantly cast out of mainstream discourse – institutionalised systems are not created for them, and they do not serve them. The oppressed are constantly reminded of their alterity, while the privileged occupy the mainstream.

Privilege, therefore, is just the experience of NOT facing the brunt of oppressive power systems, like patriarchy or cis-heteronormativity or casteism or ableism. These systems create conditions that systematically over-empower certain groups. Peggy McIntosh made this concept popular in her essay, White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack, where she listed examples of the things that she took for granted due to her white skin. She states, “As a white person, I realized I had been taught about racism as something which puts others at a disadvantage, but had been taught not to see one of its corollary aspects, white privilege, which puts me at an advantage.”

As an upper class, upper caste, fair-skinned woman, I was born with several kinds of privileges. Much of this privilege that we carry is so fundamental to our identities that we rarely examine them or think about the power structures that operate in order to make it possible for us to hold this privilege. Identity politics, like feminism or anti-caste movements, seek to make privilege visible. They try to highlight the advantages that the privileged carry, stark against their absence in the oppressed. In this article, I examine the privileges I was born with, and some that I wasn’t.

Among the privileges I hold are

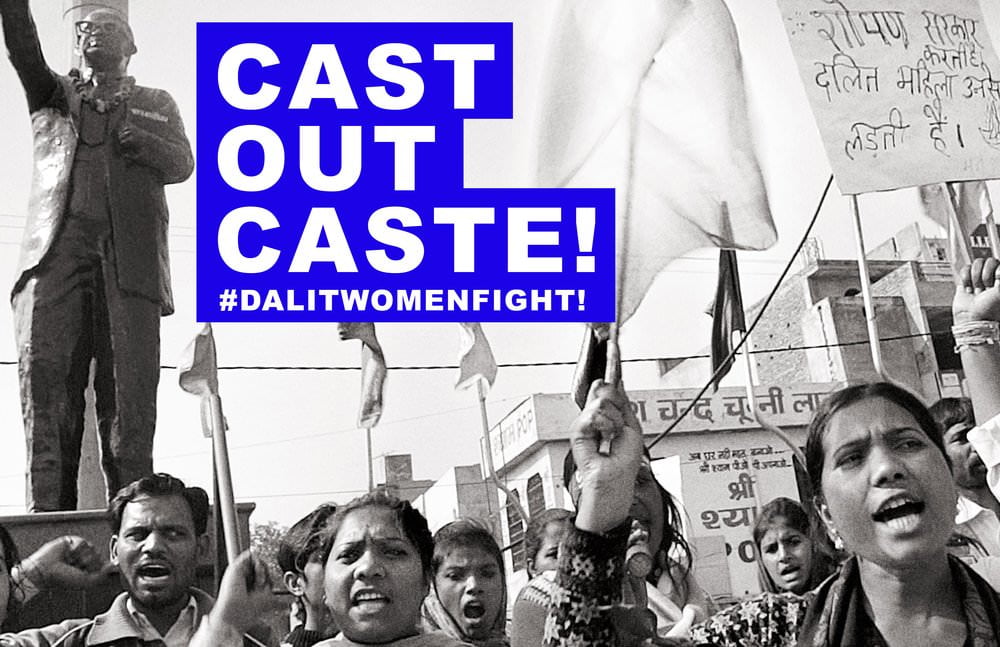

Caste privilege: I had no idea what my caste was until my second year of university. I had never been affected by it, and hence, I was oblivious to it. This is the clearest way privilege works – by rendering itself invisible. Being unaware of my caste privilege was the clearest symptom of my caste privilege. I will never have my admission and progress in university doubted or dismissed because of affirmative action policies. My achievements will be lauded as a result of my “hard work”; my caste privilege never being taken into account, while any achievements by lower-caste peers will be ignored in favour of scoffing at their reservation category. My family’s upper-caste privilege has allowed me easy access to education. With even my grandmother holding an MA degree, I never had to doubt the fact that I would receive the best education possible. I have never gone to school and made to feel like I don’t belong, been asked to clean toilets because of my last name, or been stigmatized to the point of suicide.

Class privilege: My caste privilege certainly lends itself to my class privilege, as the two intersect widely – 93% of Dalits live below the poverty line. I have the luxury of never going hungry and being able to take education for granted. I have the luxury of not immediately getting a job after graduation – I can take as much time as I need to “figure it out” and “follow my heart” (all implicitly class-tinted truisms). I can walk into malls or restaurants with watchmen not treating me with suspicion and disrespect, a mobility of access not granted to the lower class.

Religious privilege: While I personally identify as an atheist, I have an outwardly Hindu sounding name, which cloaks me in the privilege of hegemonic Hinduism. Being viewed as a [upper-caste] Hindu means I will never be treated like a cultural outsider on the basis of my name or religious practices or my eating habits. I do not have to prove my patriotism repeatedly for fear of false terrorist charges being slapped on me. I will never be discriminated against in the search of houses or jobs, that are frequently denied to Muslims on the basis of their religion.

Cisgender privilege: I am a cis-woman. This means that the body that I was born with and the gender identity I identify with are aligned. I have never had to face the difficult process of coming out as a transperson. I do not have to face constant transphobic questions on what my genitals look like, or how I will have children, or the mechanics of my sex life. I have the privilege of walking down a road and not having people cross the road in order not to run into me. Cis-privilege means that I am not painfully reminded of society’s exclusion of me every time I fill a document asking to check boxes marked M or F. For the most part, I can rely on police protection instead of being systematically harassed, raped and imprisoned by them because of my gender identity.

Heterosexuality privilege: As a heterosexual woman, I am protected by India’s laws. My right to love and engage in sexual activity is not deemed illegal. I can watch television and see my understanding of romantic love reflected in the many films I watch. I do not have to live on the shadows of acceptance, my choice of partner being hidden from that uncle or the nosy neighbour, for fear of ostracism. I will never have to face the anxiety of coming out to my parents or friends, and often put those relationships at stake in the process, or worse, experience corrective rape as a method to “straighten me out”.

Ability privilege: As a mentally and physically able-bodied person, I do not face the oppression that comes with being disabled. Everyday objects and buildings are designed for me to use. My choice of university or workplace is not limited to those that offer wheelchair accessibility. I do not have to look for subtitles every time I want to watch a documentary screening. My body and its abilities are not made into swearwords like ‘retard!’ or ‘lame!’, or into the punchline of a Helen Keller joke.

These privileges do not exist in isolation. They intersect with each other to create a multiplicity of oppressive relationships – a matrix of domination, as Patricia Hill Collins puts it. But privileges and oppression are not mutually exclusive of each other. One can be victim of certain kinds of oppression and complicit in other kinds of systems of oppression, just like I, as a woman am subject to the oppression of patriarchy, yet as an upper caste, am complicit in the oppression of casteism.

Oppressions too, do not exist in isolation. In fact, they interact in specific ways to produce specific kinds of lived experience – experiences that those with privilege never have to face, or even consider. This interaction of oppressions is called intersectionality. For example, the experience of a Dalit transwoman has the intersection of three systems of oppression that interact to produce a specific experience that cannot fully be seen when considering the oppression of Dalits, or women, or transpeople, in isolation. Read this account of a Dalit woman talking about the exclusivity of both feminist movements and Dalit movements that do not take into account her caste or gender status, respectively.

Finally, I come to the last kind of privilege discussed here – one that I do not occupy. (Keep in mind that this is not an exhaustive list of privileges. Neither are the examples identified in each kind exhaustive of the atrocity against the oppressed.)

Male privilege: Being a [cisgender] man automatically entitles one to a bunch of privileges. Right from being the preferred sex at birth, men live their lives being valued much more highly in society than women. They are much less likely to be raped, harassed or sexually abused as they go about their daily lives – in the home, on the streets, or in the workplace. Excluded from the expectations of childcare and homemaking, they are allowed to focus solely on personal growth and career-building which adds to their societal value, while domestic work is not considered productive labour. Being a man confers upon them the privilege of self-worth, something that is constantly whittled away from women in several ways – from being seen as baby-making machines to being valued exclusively for our physical appearance to body-shaming (so that this coveted physical appearance reaches unattainable standards).

So now what?

Acknowledging privilege is an uncomfortable process. It might make you feel guilt. It might make you defensive – but I didn’t ask for this! Unfortunately, giving up privilege is not really an option. We are born into our privileges, and while we can adopt some practices that shed us of directly oppressive practices that we are complicit in, we cannot entirely rid ourselves of our privilege.

So how do we contribute to social justice movements we believe in, while occupying the privileges we do? How do we, in other words, be good allies to minorities?

Acknowledging our privilege is definitely the first step, but it cannot be limited to that. Some identity politics theorists have criticised the ‘acknowledgment of privilege’ as being nothing more than a cathartic way for the privileged to get over the guilt associated with privilege.

You can push back on privilege in a number of ways. Challenge those systems that accord privilege to you and not to others. It is very important for you to speak out to members of your own social group when they undertake practices that reify privilege. Men should stand up to their male friends when they are making sexist jokes. The able-bodied should demand wheelchair accessibility in the buildings they frequent. Producers of media should strive to represent more marginalised categories in their TV/films/comics/novels to increase representation.

But the most important way to be a good ally is listen. Make sure your voice is not drowning out the voices of the marginalised. The voices of the privileged often occupy centre stage – there are constantly reports of all-male panels talking about feminism, and all-Savarna academics writing about Dalit movements. As a holder of privilege, one needs to take the back seat and make sure one listens to the lived experiences of the oppressed, as these are often never heard.

Further readings:

- Privilege 101: A Quick and Dirty Guide, Everyday Feminism

- 4 Ways to Push Back Against Your Privilege, Black girl Dangerous

- So You Call Yourself an Ally: 10 Things All ‘Allies’ Need to Know, Everyday Feminism

- Dalit Feminism, Round Table India

About the author(s)

Asmita is a Freelance Communications Consultant, and specialises in leading digital advocacy campaigns for social and gender justice issues. When not using social media for work, she uses social media for fun (and a healthy dash of existential despair).