The well-heeled and sharp Maya Sarabhai, one of the central characters from what is fast being declared one of the most beloved series to ever have graced Indian television, is everybody’s darling. I have loved her too. And yet, today, something about this uncritical popularity that she—and the show Sarabhai v/s Sarabhai—enjoys doesn’t make sense, it doesn’t quite fit.

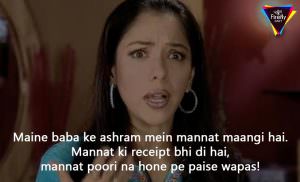

That Maya Sarabhai reeks of class snobbery is a point too obvious to be made. That she makes her audience — composed primarily of the economically well-off — snigger, is also well-known. But how does the self-professed middle class adore her when all her digs are really supposed to be aimed at them and their ilk?

Moreover, in a time when everybody is woke and even the smallest utterance — textual or extra-textual — even if supposedly well-intentioned, is subject to careful scrutiny for its politics, how does Maya Sarabhai get away with an almost offensive insensitivity to how others — those less privileged than her — live? How does she remain so beloved that there are memes dedicated to her, online discussion forums list her character as the show’s USP, when really, the one thing everyone is eagerly looking forward to in the show’s second edition is the savagery with which Maya might demolish daughter-in-law Monisha?

Most people I know say that they turned to this show because it was a breath of fresh air. A relief from the usual saas-bahu sagas that greeted them on television otherwise. This relief, they say, is provided by a stellar cast, memorable characters and a very original script with scintillating wit and humour.

If we were to try to look dispassionately at the originality in the show’s plot, one suggestion would surely be that it repackages the power struggle between a mother-in-law and a daughter-in-law — with poor and sincere husband sandwiched helplessly in between — and plays it out in decidedly class terms. While in most TV soaps, our sympathies are won by and reserved for the daughter-in-law, in this particular show, all the textual cues generate a cautious or headlong admiration for Maya’s wickedness.

While ‘regressive‘ TV soaps hinged their drama on whether a diya extinguishes itself to foretell bad luck and the lengths to which — under the watchful and willing-her-to-fail gaze of the mother-in-law — the bahu of the house would go to avoid such an eventuality, ‘progressive’ ones like Sarabhai v/s Sarabhai don’t do drama. They only do laughter.

But when Maya laughs at Monisha, and we laugh with her, who then are we laughing at? At Monisha? At her habits emblematic of the middle classes? Or at ourselves—the self-professed middle class—as some of my friends would have me believe? To understand this better, let’s take a closer look at the kind of digs Maya usually takes at Monisha.

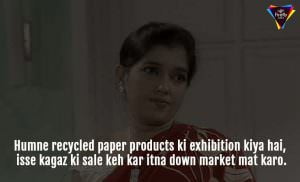

The first kind has to do with what is seen to be her incorrigible bargaining and the desire to get the most out of a deal. The second has to do with Monisha’s reluctance to throw anything away and her yearning to milk the last drop of value out of any commodity that comes her way. The third kind of taunt category that Maya subjects Monisha to is her language. They are directed at her use of ‘downmarket‘ phrases which are typically Hindi, or English phrases that are redeployed in popular circulation such as ‘Cheers karte hain’ (let’s cheer) for raising a toast.

The first kind has to do with what is seen to be her incorrigible bargaining and the desire to get the most out of a deal. The second has to do with Monisha’s reluctance to throw anything away and her yearning to milk the last drop of value out of any commodity that comes her way. The third kind of taunt category that Maya subjects Monisha to is her language. They are directed at her use of ‘downmarket‘ phrases which are typically Hindi, or English phrases that are redeployed in popular circulation such as ‘Cheers karte hain’ (let’s cheer) for raising a toast.

Closely related are Monisha’s habits of cultural consumption i.e. her own addiction to saas-bahu sagas — themselves parodic renditions of soap operas with names that lay out the absurd farce that they contain such as Uska Pati Sirf Mera Hain (Her Husband Belongs to Me).

The fifth kind of taunt is making fun of Monisha’s faith, and the associated practices she swears by such as asking for a mannat or fasting. The sixth category of very general taunts seem to carry these threads together and mock Monisha’s public persona—the way she carries herself in public or more specifically, the way she is unable to act dignified at mother-in-law Maya’s soirees, or even at fancy restaurants.

Also Read: Female-centric Hindi Films And Women Who Watch Them

Maya of course stands in stark contrast to all the character defects she identifies in her daughter-in-law. She never bargains because she cannot be seen to care for money. She never reuses anything. Her English is impeccable, and she never uses mongrelized speech. She only patronises ‘high culture‘ and is a regular at the (presumably English) theatre. She is certainly not superstitious, not even religious. And she most certainly knows how to operate smoothly at fancy restaurants, thank you very much. It goes without saying that all of these are the direct dividends of her economic and the ensuing cultural capital. But in the way we look at her and love her, this crucial fact is erased.

Maya Sarabhai then embodies this ideal of the cosmopolitan woman, suspended in a socio-cultural vacuum, whose very positioning as a neutral, apolitical agent is reflective of the insidious ways in which we frame and see the urban, educated, sophisticated, rational liberal. In other words, she is the anti-aunty of our popular consciousness. Monisha is everything that we—as The Woke People—Other with respect to our own socio-economic origins, and then write cutesy pieces about.

Monisha is borderline aunty—the aunty we like to demonise and make fun of, right from the one at the parlour, to the ones in our housing societies, to the ones we meet at family functions. The aunty who stands for all the ignorance, illiteracy, noseyness and positively hideous oppression of other more privileged girls who have an education and the benefits of more freedom and options. The aunty who has no saving grace. The aunty who is nothing but guilty of complicity in patriarchal structures. The aunty who never suffers. And she is also the aunty we can make fun of precisely because of our class location. She is the aunty who watches Uska Pati Sirf Mera Hain while we enjoy seeing a mother lord it over her son’s wife because said wife gulps down ragda pattice even as our heroine tastefully picks at her Caesar Salad.

Monisha is borderline aunty—the aunty we like to demonise and make fun of, right from the one at the parlour, to the ones in our housing societies, to the ones we meet at family functions. The aunty who stands for all the ignorance, illiteracy, noseyness and positively hideous oppression of other more privileged girls who have an education and the benefits of more freedom and options. The aunty who has no saving grace. The aunty who is nothing but guilty of complicity in patriarchal structures. The aunty who never suffers. And she is also the aunty we can make fun of precisely because of our class location. She is the aunty who watches Uska Pati Sirf Mera Hain while we enjoy seeing a mother lord it over her son’s wife because said wife gulps down ragda pattice even as our heroine tastefully picks at her Caesar Salad.

To be sure, the universe of the show that Maya inhabits is comfortable mocking her and her world. Some sequences in the show do point to the shallowness of a modernity, those which Monisha’s mother-in-law peddle, such as the one where Maya organises a fundraiser to fight alcohol addiction among the underprivileged, by putting on sale cocktails for her friends. Most notably, Maya’s husband Indravardan Sarabhai is constantly satirizing and thereby undermining his wife’s sophistication and authority.

To be sure, the universe of the show that Maya inhabits is comfortable mocking her and her world. Some sequences in the show do point to the shallowness of a modernity, those which Monisha’s mother-in-law peddle, such as the one where Maya organises a fundraiser to fight alcohol addiction among the underprivileged, by putting on sale cocktails for her friends. Most notably, Maya’s husband Indravardan Sarabhai is constantly satirizing and thereby undermining his wife’s sophistication and authority.

The question to ask is, as the show’s second season takes off as web-series, will we be able to inject our love for Maya with a similar criticality? Because, it’s about time we did.

NOTE: Sarabhai v/s Sarabhai’s second season launched as a web series on Hotstar in May this year.

Featured Image Credit: Hotstar

About the author(s)

Pradnya Waghule teaches Communication at a Mumbai college.

I think the idea is to laugh at ourselves – something we all should know how to do. If it were Sahil instead of Maya doing this, it would have been an entirely different case.

Um..it is a satire?

The comments above said what I wanted to.