Posted by Meena Saraswathi Seshu, Laxmi Murthy and Aarthi Pai

What is it about sex work that arouses much passion amongst many feminists? From outrage over the exploitation of women’s bodies to pity for the hapless victims of male lust, it has been difficult to view sex workers as going about the daily business of earning a livelihood by providing sexual services in exchange for money. While victimhood and exploitation are easy to empathize with and mobilize around, money for sex has engendered not just noisy public debate, but quiet squeamishness even among several strands of feminists. Even feminists who advocate liberation from restrictive sexual mores have generally not viewed commercial sexual transactions as “work”.

What is it about sex work that arouses much passion amongst many feminists? From outrage over the exploitation of women’s bodies to pity for the hapless victims of male lust, it has been difficult to view sex workers as going about the daily business of earning a livelihood by providing sexual services in exchange for money. While victimhood and exploitation are easy to empathize with and mobilize around, money for sex has engendered not just noisy public debate, but quiet squeamishness even among several strands of feminists. Even feminists who advocate liberation from restrictive sexual mores have generally not viewed commercial sexual transactions as “work”.

Feminists and sex workers have only recently begun to talk to each other. The dialogue has been difficult mainly due to the awkwardness, hesitation and hostility from feminists towards sex workers and those working for their rights. The notion that sex work debases women and transforms them into objects of control and exploitation is premised on the belief that a cash transaction strips a supposedly intimate act like sex of its inherent worth.

It is therefore believed that no ‘good’ woman would actually opt for sex work as a viable livelihood option and the women who ‘voluntarily’ do so do not fully comprehend the inherent patriarchal sexual exploitation of their bodies and selves and are therefore labouring under “false consciousness”. The growing visibility of male and transgender sex workers has not led to much rethinking or reframing of classic feminist positions around the “poor helpless prostituted victim woman”.

The women’s movement has for several decades engaged with issues related to the body. The conflation of sexuality and reproduction, the reduction of women into uteruses and vaginas and the fragmentation of women in reproductive health policies demanded an engagement with the construction of the female body and ‘control’ over it.

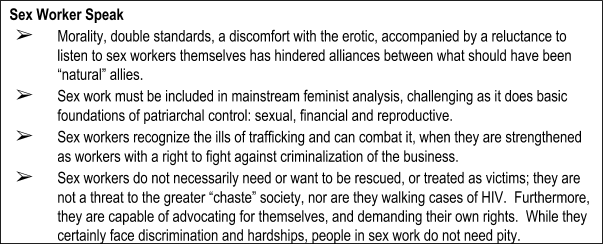

Where contraception and fertility control mark the intersection of female sexuality and reproduction, sex work marks the intersection of female sexuality and work. This is a convergence that has demanded a complex response that is still evolving. Morality, double standards, a discomfort with the erotic as well as unease about multiple sex partners, accompanied by an unwillingness to listen to sex workers themselves has hindered alliances between what would have been “natural” allies. Feminist theory and practice – a powerful liberatory force challenging inequities in every sphere – seemed to have faltered, and even failed, when it came to the issue of commercial sex.

Sex work marks the intersection of female sexuality and work

The debates around trafficking further bolster the idea that sex work is inherently violent. Anti-trafficking rhetoric holds that bodies are unwillingly ‘sold’ and transported across borders. Exchanging sexual services for money [sex work] is conflated with selling of a body to another [trafficking]. A section of feminist activists thus regards prostitution as ‘female sexual slavery’ and ‘sexual victimhood’. These perceptions echo the early reformist discourse, which views women as needing to be protected, preferably by laws, from lustful men. The victim trope has runs through several positions on prostitution and trafficking.

However, trafficking, in addition to the element of force and deception which doubtless is a serious crime, must also be viewed as an issue of poverty that causes many women to willingly enter into agreements with traffickers because they desperately seek better livelihoods, escape from home-grown violence, poverty, conflict, or displacement – in short, a better life. In many situations, human smuggling (transporting humans without proper documentation) is fuelled by people’s desire to migrate for better prospects. Evidence shows that sex workers who have been trafficked later choose to remain in sex work despite opportunities to leave after ‘rehabilitation’ by the government or NGOs.

Anti-trafficking activists who have gained support from some radical feminists have argued that sex work itself is violence mainly because of their belief that all entry into sex work is involuntary, forced, through deception, bribed, blackmailed or lured and sexually exploited by unscrupulous traffickers. Their argument especially about minor girls is valid but the underpinning of abolitionism that governs their arguments takes the focus away from finding and punishing the traffickers to raiding, rescuing and rehabilitating sex workers without consent.

Exchanging sexual services for money [sex work] is conflated with selling of a body to another [trafficking].

The fracture in this method comes from the idea that adult women who were trafficked as children or otherwise are pulled into an indiscriminate rescue and rehabilitation plan disregarding their ability to consent at the time of rescue. In these policies, the lines between trafficking, child prostitution and adult sex work—however distinct in reality—are purposely blurred.

Sex workers are increasingly articulating sex work as work, as a business, and do not consider themselves as either criminals or victims. Because feminism posits prostitution as violence, this viewpoint forecloses any discussion over whether sex work can be a livelihood option. In order for the stigma of discrimination to end and fundamental rights to be extended to sex workers to pursue their livelihood in safety and dignity, societal perception must be transformed. Sex workers in the business recognize the ills of trafficking and child sexual abuse and are taking measures to combat these crimes. This is only possible if sex workers are strengthened as workers with a right to fight against criminalization of the trade.

Also read: Why Is Sex Work Not Seen As Work? – Part 1

There is a need to examine the troubled relationship between large sections of feminists, the human rights discourse and sex workers’ rights in negotiating the knotty terrain of sexual politics and its interface with labour rights. Over the years, collectivization, community mobilization and fighting for the right to a ‘voice’ has helped centre the debate on sex work by the people in sex work themselves. The women’s movement is not a monolith, and there is need to forge alliances between those working towards autonomy, dignity and fundamental rights, re-defining these to include the most marginalized of individuals and communities.

Sex workers are increasingly articulating sex work as work, as a business, and do not consider themselves as either criminals or victims.

An additional challenge is the caste dimension. At the Chalo Nagpur mobilization of women’s rights activists against fascism earlier this year, many Dalit rights activists took strong objection to the articulation that sex work is work. Their contention is that ‘prostitution’ is upper caste exploitation of dalit women both by upper caste male clients and upper caste women who work on sex worker rights in the country. They contest the ‘right to sex work’ articulation of collectives like Veshya Anyay Mukti Parishad (VAMP) and the National Network of Sex Workers (NNSW) whose membership is largely Dalit women. These debates are contentious and fractious, but must continue in order to build alliances amongst the most marginalized sections of Indian society.

Sex work is work

While human rights violations are common throughout India, they are particularly prevalent in the lives of people involved in sex work. Discrimination against sex workers in India is as much an issue as the discrimination faced by other marginalized groups along lines of class, caste, diverse sexualities or religion. Interestingly, the advent of HIV/AIDS in the 1980’s saw governments make great efforts to target sex workers in the global and national responses to the HIV epidemic. Sex workers were targeted as vectors of spread of HIV and governments were determined to save the ‘bridge population’ of men, using sex work interventions only as a means of protecting ‘respectable’ wives from HIV.

In many parts of the country, sex workers turned this around and made it an opportunity to focus attention on the health, safety and rights of sex workers. However, this picture is complicated by politically powerful faith-based constituencies, an anti-trafficking movement that denies the agency and rights of sex workers, and powerful funders. United Nations positions demonstrated some leadership on sex worker rights early in the epidemic but later appeared to acquiesce to prohibitionist views.

However, sex workers are mobilizing and articulating their rights as never before. National Network of Sex Workers, a coalition of sex-worker led organization and allies with a membership of about 50,000 women, men and transgender sex workers, is vociferous in the articulation of sex workers rights. The NNSW envisions a world where sex work is recognized as work; a world that is just and does not criminalize sex work; where adult men, women and transgender persons in sex work have the right to earn through providing sexual services; live with dignity and remain free from violence, exploitation, stigma and discrimination.

Also read: Why Is Sex Work Not Work? Lessons Learned From Sex Workers’ Rights Movement – Part 2

The judiciary is also moving in the direction of recognizing sex workers’ right to livelihood. The Supreme Court in the Buddhadev Karmaskar v. State of West Bengal [Criminal Appeal No. 135 of 2010], has also opined that sex workers have a right to dignity. In 2011, the apex court appointed a Panel to deliberate on various aspects of sex workers’ rehabilitation and to provide them with a dignified life. The three terms of reference of the Panel include prevention of trafficking, rehabilitation of sex workers who wish to quit sex work and conditions conducive for sex workers to live with dignity in accordance with the provisions of Article 21 of the Constitution.

The Justice Verma Commission also acknowledged that there is a distinction between women who are trafficked for the purpose of commercial sexual exploitation and adult consenting women who are in sex work of their own volition. The Justice Verma Commission set up by the Government of India in the aftermath of the gang rape in December 2012 was mandated to “Look into possible amendments of the Criminal Law to provide for quicker trial and enhanced punishment for criminals committing sexual assault.”

The Justice Verma Commission report introduced a chapter on trafficking and recommended amongst others the amendment of Section 370 of the Indian Penal Code which deals with the offence of Trafficking of Persons. Inappositely, the definition of the term “exploitation” included “prostitution” itself. This in essence meant that “prostitution” would now be interpreted as exploitation in the Amendment.

Sex workers envision a world where they live with dignity and remain free from violence, exploitation, stigma and discrimination.

The NNSW appealed to the commission for clarification and the committee responded clarifying that the thrust of the amended Section 370 IPC was to protect women and children from being trafficked. The committee had not intended to bring within the ambit of Section 370 IPC sex workers who practice of their own volition. Further that the recast ought not to be interpreted to permit law enforcement agencies to harass sex workers who undertake activities of their own free will, and their clients. For the first time, a government-appointed commission recognized that there is a distinction between women who are trafficked for the purpose of commercial sexual exploitation and adult consenting women who are in sex work of their own volition.

Calling for the separation of efforts to combat trafficking from impinging on the rights of sex workers, Rashida Manjoo the Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women in her report submitted by the Human Rights Council to the UN General Assembly in April 2014 noted that sex workers in India are “Exposed to a range of abuse including physical attacks, and harassment by clients, family members, the community and State authorities“. It further stated that “Sex workers are forcibly detained and rehabilitated and consistently lack legal protection“; and that they “Face challenges in gaining access to essential health services, including for treatment for HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted diseases“. The report reiterated that conflating sex work with trafficking has led to assistance that is not targeted for sex workers specific needs and has also led to coercive rehabilitation measures.

For sex workers in India to access and enjoy their rights, massive misgivings and stereotypes about sex work need to be broken down. Sex workers do not necessarily need or want to be rescued, or treated as victims; they are not a threat to the greater “chaste” society, nor are they walking cases of HIV. Furthermore, they are capable of advocating for themselves, and demanding their own rights. While they certainly face discrimination and hardships, people in sex work do not need pity.

Also read: Notes From A Sex Worker On Providing Services To Clients With Disability

Featured Image Credit: Sex worker protest in Maharashtra, India

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.

Sex work is gave to our society a good family atmosphere* if we need good family we will support sex workers* that mean, oxygen and hydrogen combination to water formula theory*