Phoolan Devi’s story is extraordinary. She was extraordinary!

She withstood horrendously oppressive circumstances, was the victim of systemic structural injustice and she not only survived to tell the tale, but she came out on top. While the intention of this piece is not to hold up individual exceptionalist acts as the solution to trump structures that marginalize and tyrannize, Phoolan Devi is an example that needs to be told and retold because the woman’s heroism defies most narrative arcs that our caste-patriarchy needs most to survive.

Given just how unfathomable her figure and life-story seems, it is perhaps not surprising, that today, any reliable account of the events of her life seem difficult to come by. As a legend, her figure seems to have spawned mythologies. However, most accounts do largely agree on the following.

Early Life

Phoolan was born on August 10, 1963 in Uttar Pradesh’s Ghura Ka Purwa. Born in the Mallah community of boats(wo)men, according to some reports, she was the fourth child in the family. (In various parts of the country, the Mallah community is included either under the OBC or the SC category. Read this account for details of the kind of violence the community had to face and to understand how the anger that was directed towards Phoolan was not least because of her position as a lower-caste woman, who challenged the status quo).

Narratives that celebrate her extraordinary courage and resilience often trace the first outward manifestation of her spirit to an incident when she was around 11 years of age. While the details are unclear — some reports say she was fighting for a piece of land unfairly usurped by her cousin, some others say it was to protest this cousin’s decision to chop off a neem tree that stood on their land — she is said to have staged a dharna against what she believed was wrong, against members of her own family.

Most accounts here stress the reputation she had gained as a trouble-maker, and that the family sought to get rid of her. They got 11-year-old Phoolan married to a man who was at least 23, though most accounts state he was 30. Unhappy in her marriage, she returned to what was once home.

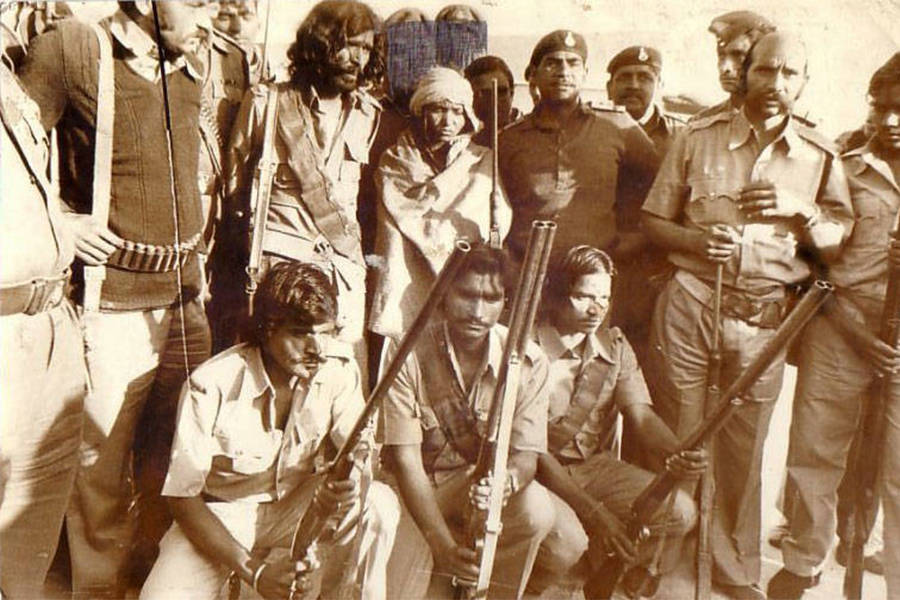

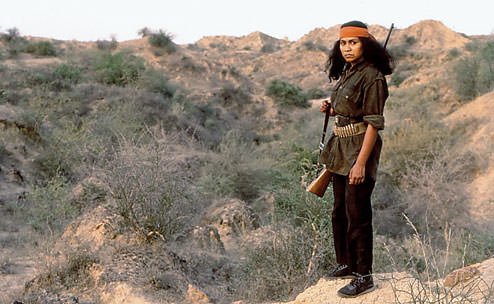

Life as a Dacoit

While it is unclear whether she was abducted by a gang that she was forced to be a part of or whether she walked into one of her own accord, it is widely believed that around 16, she was part of a family of dacoits. When Vikram Mallah – the man who assumed reins of leadership after murdering the previous leader Babu Gujjar supposedly because he sexually harassed Phoolan – was murdered by a rival, upper-caste faction of Rajputs, Phoolan was abducted and locked up. In Behmai, she was gangraped for close to three weeks. It is important to note here that Phoolan herself never spoke of this incident.

Behmai Massacre

When Phoolan did eventually escape, she formed and headed her own gang only to return to Behmai on 14 February, 1981. In what is sometimes referred to as the Behmai massacre, she rounded up 22 Rajput men of the village, and had them all killed.

Apparently this is the day she started being referred to as Phoolan Devi, the honorific Devi suggesting the respect, awe and fear she commanded from this time onwards. While this act made Phoolan Devi a target of upper caste anger – which resulted in her assassination in 2001 – it was also perceived to be an act of retribution and one that sought to redress not just the wrongs Phoolan has to endure, but those many injustices that lower castes, and lower-caste women in particular had to face on a daily basis.

The next two years, Phoolan spent on the run from the police. Legend also has it, that this time she looted the rich and redistributed the plunder among the poor, but apparently, this is a version that has never received any confirmation.

Life as a Parliamentarian

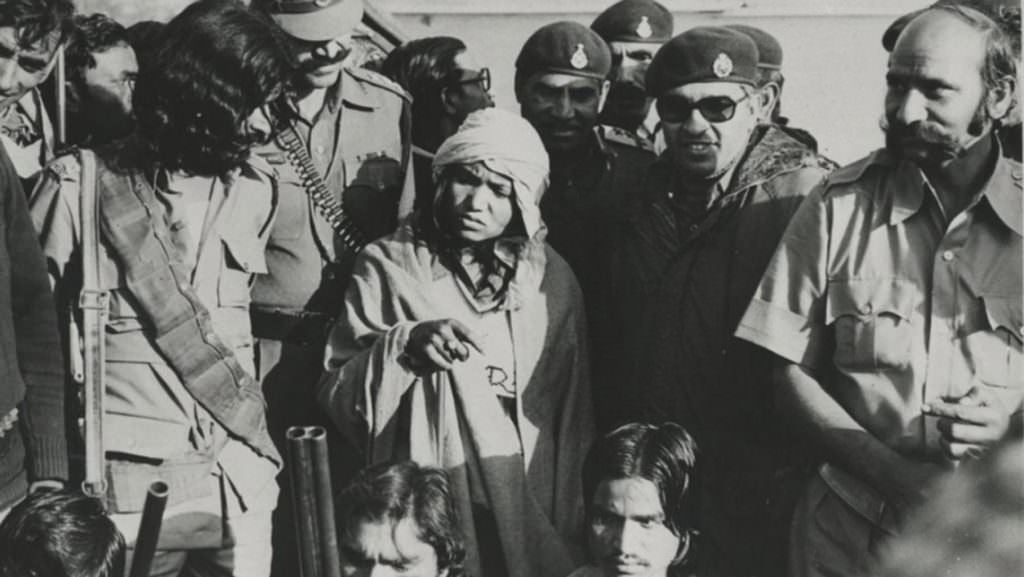

Phoolan then decided to surrender to the police but on certain conditions. She was not to be awarded a death penalty. In addition her family was to be given a piece of land. She then spent 11 years in jail at the end of which she was cleared of all 48 charges she was put behind bars for.

After two more years – in the duration of which Shekhar Kapur’s film on Phoolan’s life called The Bandit Queen was released to widespread acclaim and without her consent, and against which Phoolan sought a restraining order – the Samajwadi Party gave her a ticket to contest from Mirzapur in UP which she won to enter the Lok Sabha. She won her second term in 1999 and was assassinated as a sitting MP at her residence in Delhi – a crime for which Sher Singh Rana was convicted in 2014. His motive? To avenge the massacre at Behmai. In addition to her work as a lawmaker, Phulan had also set up the Eklavya Sena, which was to help teach self-defence to members from lower caste communities.

Just this broad sweep across her life is enough to establish why people thought she was special. But this very impulse to celebrate her might sometimes lead us towards framing her in sensationalist terms, forgetting the real person behind it all. As Presley has noted,

“As a Parliamentarian, she fought for women’s rights, an end to child marriage, and the rights of India’s poor. In a Che Guevara-type revision of history, though, Devi is remembered as a romantic Robin Hood figure, robbing the rich to help the poor, and not as a politician working to enact structural change in India’s social hierarchies.”

Yes, we need to recognize her spirit and commemorate it. But we need to do even more heavy-lifting when it comes to documenting her life and her work so that anxiety-ridden accounts about her place such as this Wikipedia entry can be adequately put into perspective.

About the author(s)

Pradnya Waghule teaches Communication at a Mumbai college.