A woman is stalked, chased through the road in the middle of the night in an Indian city by two drunken men driving a car much bigger than hers, until the police arrive to help her. Why was she outside her house in the middle of the night? What was she wearing? Maybe she had it coming – look at the company she keeps! And so it goes. The story repeats itself tirelessly. You can predict what ‘they’ will ask with such accuracy, that it no longer matters who is doing the asking and what is being asked.

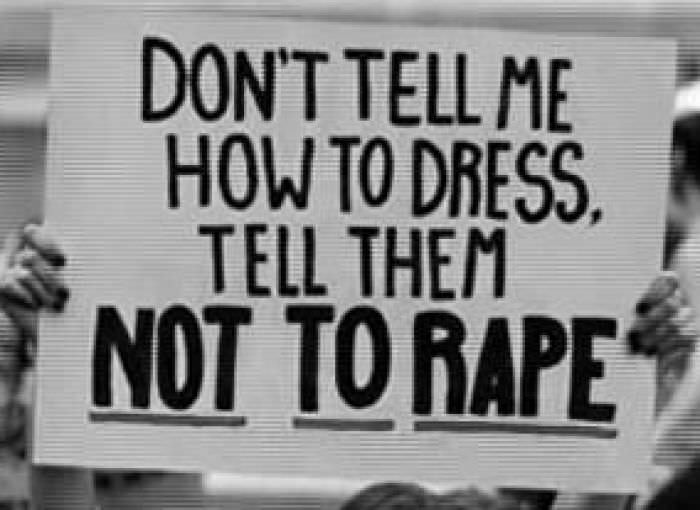

But there are also questions we don’t ask. What were the men doing in the middle of the night? Why were they driving drunk? Why were they chasing a woman and banging her window? What were their intentions? Have they done this before? Survivors of gender-based violence such as domestic violence, sexual assaults, acid attacks, stalking, sexual harassment both online and offline have at one point or another encountered such narratives.

What was she wearing? Maybe she had it coming – look at the company she keeps! And so it goes. The story repeats itself tirelessly.

Blaming the victim is convenient and also a good way to deflect attention from the real protagonists. Blaming the victim, and absolving the accused are two sides of the same coin. In fact the internalization of misogyny is so complete, that survivors constantly second guess themselves. Were they in some way responsible for what happened? Perhaps the clothes were too revealing or they had not been careful enough to not go to a poorly lit part of the city alone or they should not have that last glass of alcohol or their friendliness was taken as an invitation to flirt and do more, or her casual flirting was an invitation to have sex – the list is endless.

The characterization of victims in this manner by themselves and social institutions lead to the development of myths around sexual assault called (Rape Myths). Rape myths cut across countries, classes, races and nationalities. The Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale (IRMAS) is a scale that tries to measure attitudes towards justification of rape on a scale of I (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree), the lower the score on this scale, the higher the acceptance of rape myths. There are four sub-themes, which the scale tries to measure:

1. She asked for it (Focus on the survivor’s body language, clothes and other forms of signaling including consent –her state of inebriation, non-verbal signals like going into a room alone with a boy, acting like a ‘slut’, did not say no clearly enough, initiated kissing and thereby indicated consent to intercourse)

2. He didn’t mean to (Focus on viewing rape as a manifestation of uncontrolled sexuality of men and effects of alcohol – men get “sexually” carried away but do not intend to force themselves on women, they cannot help it because their urges are unbridled, raping purely under the influence of alcohol thus not intending to rape and/or not being aware that they are committing a rape).

3. It wasn’t really rape (Focus on what survivors did or could have done to protect themselves in the moment and the degree to which physical violence was involved – did not physically resist sex, verbal resistance is not adequate, since there were no physical injuries it cannot be called rape, no weapons were carried or used by the accused so it can’t be rape, she did not use the word “No”).

4. She lied (Focus on destroying the credibility of the survivor – post sex regret, not rape, to seek revenge on the accused, she led him on first and then regretted it, she had emotional problems, she was cheating on her boyfriend and said it was ‘rape’ so she is in the clear with him)

Although the IRMAS focuses on rape, the attributes that it tries to capture are equally applicable to any context where gender is the key determinant of violence such as stalking, domestic violence or sexual harassment. If we observe carefully, the emphasis is on diminishing or erasing the responsibility of the accused, while trying to identify both tangible and intangible ways in which survivors may have either unwittingly encouraged the perpetrators, or invited this upon themselves. This normalizes their encounters, so that the element of violence is pushed to the periphery, and the victim’s ‘moral inferiority’ is made primary.

Even where the emphasis is not on destroying the credibility of the victims, in a statement now infamous by the former CM of Uttar Pradesh Mulayam Singh Yadav, that “Boys will be boys” and thus reinforcing the myth that rape is an outcome of naturalized hypersexuality of men.

The emphasis is on erasing the responsibility of the accused, while trying to identify both ways in which survivors may have encouraged the perpetrators.

These narratives of sexual violence both by people in position of eminence as well as a form of social chatter are dangerous. What is even more dangerous from the point of redress is what occurs inside police stations, courts and judges’ chambers. Given that the legal system is patriarchal and masculinist and as Catherine MacKinnon argues the state is male in the feminist sense, the justice system often reinforces these regressive positions.

Baxi’s scholarship on rape trials in India found that rape was a “sexualized spectacle“, where discourses are advanced in courts from a position of doubt, rather than empathy for the survivor. Macmartin and Wood in their study find that judges often use sexual explanations while trying cases of pedophilia in Canada, instead of making power the pivot around which these acts revolve.

An understanding of power, and the impunity with which it is yielded, are crucial to an understanding of gender-based violence, and particularly victim blaming as an insidious use of this power. In Ms. Kundu’s instance this is obvious given the economic, social and political resources of Mr. Barala. In a recent incidence CRPF personnel molested 5 tribal girls in Dantewada district on the 7th of August 2017, during a Rakhi tying event, stands out for its deep irony as well as a faithful articulation of the linkages between sexual violence and power. The latter has not received much attention from the mainstream media perhaps because it lacks political currency, or perhaps, because the girls are tribal, or perhaps, because the location is Dantewada, or perhaps, because it is the CRPF, or perhaps, because all of these are true.

An understanding of power, and the impunity with which it is yielded, are crucial to understand victim blaming as an insidious use of this power.

In an interview to NDTV, Ms. Kundu and her father have been forthright, articulate and reflective. They have taken note of the fact that if given their own social capital (resources) and their status as insiders to the system, they can face such hurdles, what about people with far fewer resources? Not just resources had it not been for the landmark introduction of laws against stalking, among others by the Justice Verma Commission, Barnala and his friend might be free today, free to terrorize more women. While we need not have an unflinching faith in the system, laws are necessary, if not sufficient conditions, for an approximation of justice. Thus the recent regressive judgments are even more disconcerting in this context.

Let’s hope that in Ms. Kundu’s quest for justice, the Courts take a position, which understands that sexual violence is not about sex. Sexual violence is a phallic deployment of power. Otherwise a 10-year-old girl would not be pregnant in Chandigarh. Once you accept this premise, victim blaming can stop, and we can all start asking the right questions.

References

- MacKinnon, C. (2001). The Liberal State. In D. D. a. A. Ripstein (Ed.), Law and morality: readings in legal philosophy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press: pp. 218-231.

- MacMartin, C., & Wood, L. A. (2005). Sexual motives and sentencing: judicial discourse in cases of child sexual abuse. Journal of Language & Social Psychology, 24(2), 139-159.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Shalini Iyengar at the Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology and Darshana Mitra at the Alternative Law Forum for the conversations during the past few days, which have contributed to the drafting of this article.

About the author(s)

Sreeparna Chattopadhyay has a Ph.D. in Cultural Anthropology from Brown University with research interests in gender and its intersections with health, education family and the law. She is an independent researcher.