Posted by Dr. Smita M. Patil

We are being bombarded with the new age vulgate of digital India. Premises that related with the grand notions of ‘digitally empowered society’ and ‘knowledge economy’ have been added to the neoliberal Indian vocabulary. Future of India is being visualised through the native talent and information technology. Critical minds are sceptical about the detached nature of ‘the digital’ from ‘India’. In order to challenge such genuine scepticism, digital print media celebrates the contemporary obsession of designers with skeumorphism.

In other words, whatever is created in the digital world should imitate the concrete realities. To conceal the inaction of the digital field from the real surroundings, it is also argued that geeks are not “anti-social”, they are just “anti-unintelligence”. Access to basic quality education, teachers, schools, infrastructure and so on are major issues faced by the underprivileged in India. At the same time, new identities are being formed in an age of mobile phones, social media and such contemporary versions of technology have created new forms of limited, interactive practices. This article probes the ways in which caste, gender and ideology/practices of technology are interlinked in India.

whatever is created in the digital world should imitate the concrete realities.

Bharatiya Janata Party emerged as a single largest party in India in the Loksabha election, 2014. It has given its citizens a number of promises. As discussed earlier, Digital India was one of the central areas of interest in that political discourse. Activists also spoke about the corruption-less India and consequential happy, Indian life. Digitalisation of diverse sectors such as banking, educational practices, public offices have foregrounded the question of digital in the post-globalised India. Computerisation and automation have also raised major questions in India.

Also read: Analysing The Caste Bias In Private Sector Employment

‘Skill’ is projected against ‘knowledge’ and jargons such as ‘knowledge workers’ are thrown into a society where basic literacy exists as a distinct dream. The caste-ridden Indian society and its existential as well as practical questions related with dominant perceptions about digital technology are not much discussed by the professorial-‘science and technology studies’-avatars. Debates are being divided into India on the basis of left versus right, progressive politics versus identity politics and so on. Nature of such simplified, political othering needs to be emphasised when one analyses the affinities and exclusion in the context of marginalised communities and plural, digital debates.

Cyber pundits and cyber libertarian social scientists celebrate the role of Information and Communication Technologies in the eradication of rural poverty. On the contrary, low education status, complex social structure and low accessibility to Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) have expanded the digital divide (DN, 2001)1. Those connected to the internet are 35% of the population – the social composition of those with access to ICTs is dominant Indian castes, and they stand disconnected from the reality for majority of the Indian society. Thus, it accelerates the gap related with access and social mobility2.

Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujan students are utilising the possibilities of blogosphere. They are deploying YouTube to reach to the majority of people through programs like that of Dalit Camera. They have also started using Twitter and the emergence of Dalit Twitterati thus challenges the domination of Twitterati from the socially/politically privileged. One of the significant shifts is that of the emergence of Dalit-Bahujan girls/women and their new forms of digital articulations.

Also read: The Modern Savarna And The Caste-Is-Dead Narrative

Articulate Dalit-Bahujan, Adivasi girls/women are using the blogs and forms of new media to present the big questions related to Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujans in general and Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujan girls/women in particular. Interlinkages of caste and gender and its vicious formation of Brahmanic patriarchy are being unveiled through the autonomous, blogosphere of Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujan girls/women. Some of them are also using Twitter in a systematic fashion.

Certain online forums are unique in the ways in which that address the issues related with social and political inequalities. For instance, websites such as, ambedkar.org initiated a paradigm shift in the Dalit intellectual sphere through introducing the pan-Indian/diasporic Dalit articulations.

A significant shift is the emergence of Dalit-Bahujan girls/women and their new forms of digital articulations.

Another online initiative that has gained critical acclaim across the social movements in India is Round Table India. It is important to analyse the nature of the form and content of this particular online approach of resistance. Interestingly, Round Table India introduces us to a social and political world that is being neglected by the value free, peer reviewed, exclusionary, dominant academic space.

Meritocracy of the dominant and their epistemic hierarchy related with knowledge thus become critiqued through this particular anti-caste/religion scholarly-online space. It also challenges the Brahmanic-homophobia that structures the power relations between caste, gender and patriarchy. Therefore, it expands definitions and equations of contemporary resistance. It also does not follow the typical academic gimmicks that are being played in the name of social theory, Marxism, post-colonialism, subaltern studies, feminism and so on. On the other hand, it transcends the boundaries between theory and empirical approaches. It does not divert itself from the harsh realities of the oppressed in India. Hence, it maps the contemporary world of the marginalized in vivid manner.

Round Table India introduces us to a sociopolitical world that is neglected by the value free, peer reviewed, exclusionary, dominant academic space.

Simultaneously, history is viewed as a significant path through which one has to reclaim the social space and self-dignity. Hegemonic historical approaches consequently are probed to establish the history of the people from the below. Recovering the memory thus becomes the essential way to declare the independence from the tangible and intangible forms of the dominant-power structures. This online space largely foregrounds a meaningful intellectual-activist premise for the restoration of social justice.

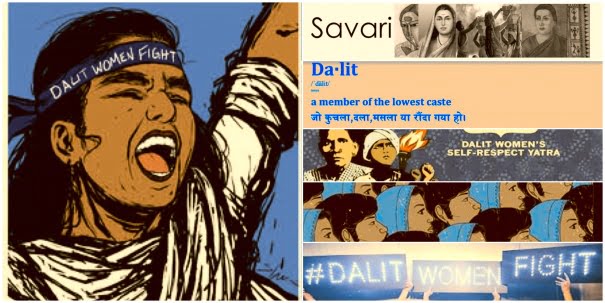

Another online forum that challenges the Brahmanic sisterly politics is named as Savari. It has constructed certain reflexivity that empowers the Adivasi, Dalit women. It revisits the larger questions of “self, family and community” (in the words of Savari team). One of the striking aspect of this online forum is that it provides an alternative, online forum of the marginalised women from South Asia. As a result, it brings forth epistemic challenge to the so called dominant category of ‘South Asian Feminism’ that creates apolitical pastiche out of disconnected issues. Social composition of intelligentsia and the ideology of South Asian Feminist circle is elitist because it does not provide any critique to the interlinkages of caste, gender and patriarchy.

Also read: Who Is The “Perfect” Dalit Woman? On The Self-Assertion Of Identity

One needs to explore the manner in which the new online sphere impacts the students. In my conversations with Advasi, Bahujan, Dalit students (boys, girls) a year before on the emergence of blogs such as Savari, Round Table India and Dalit Camera across Delhi university, JNU and other institutions they narrated the various experiences regarding Information and Communication Technology, online activism, negative and positive impact of ICT and so on. Most of the students requested not to reveal their names.

A Dalit girl student argued that Twitter helps us to “understand the oppression of the people across the globe and helps her to identity with the cause of the Dalit women who suffer from internal/external patriarchy”. She further said that “experiences/knowledge of the racially, subjugated women can be read via Twitter”.

Another Bahujan woman argued that “reading and writing coexist in the development of blog and it is essential for the Dalit-Bahujan community to have access to internet, website, blogs and so on”. Masculine realm of the technology thus is being subverted by Dalit-Bahujan girls’ interest in new media technologies.

Another Dalit girl who is a student of computer science said “Dalits have to learn new technologies. It is important for the growth of the community. Dalit girls will get a job that does not have any stigma of caste. Financial autonomy of Dalit girls can be achieved through securing technology based education”. Some of them questioned the credibility of the argument that technology can provide social mobility to the women.

A Dalit woman public servant observed that “Most of the Dalit families are poor…therefore technology comes after getting the basic facilities”.

Social media is viewed as a digital space where Dalit-Bahujan, Adivasi can express their views. A Dalit woman activist argued that “Mainstream media does not publish our ideas. Social media is a major help to us.”

Another Bahujan girl-research scholar said “Blogs like Savari empower us to move beyond Brahmanic feminist rhetoric. It is a new feminist intellectual-ideology/practice that is grounded in the epistemic space of Adivasi, Dalit, Bahujan women”. Blogosphere or Twitter or social media has created a paradigm shift in the understanding about the representation of women in social movements.

Blogs like Savari empower us to move beyond Brahmanic feminist rhetoric.

An Adivasi girl student said “Our women are being stereotyped as weaker, but our generation is converting new media into a new form of resistance”. These views reflect the issues of Dalit-Bahujan social/political development, identity formation and so on.

Broadly, the opinion of the Dalit-Bahujan women leads us to conceptualise the relationship between the technology and new theorisation of Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujan political perspectives.

One of the central questions that can be raised that how far it is relevant to project Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujan woman politics online. Another challenge before the groups based on the anti-caste cum gender politics is that these technology and its forms are part of the surveillance; therefore is it reductionist to read their politics via the binary opposition to access/exclusion related with media technology? In addition to these core issues, one can ask how far they are successful in converting their community into a new workforce based on the cultural and social capital.

In other words, how far the mere knowledge of certain skills related with digital technology can empower the women from the most, marginalised sections in the Indian society. How Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujan girls/women use technology is able to undermine the hegemonic, brahmanic construct related with science and technology. It is relevant to explore the role of these women as new messengers of critical anti-caste politics and they can achieve a new dimension through transforming it into new media entrepreneurship as an antidote to the caste based-socially regulated Indian economy.

“Communicative capitalism”3 is being challenged through peer to peer initiatives and what that paradigm shift offers to the Indian realm of online Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujan sphere. Rural-urban divide also restructures the caste cum gender based digital divide. Triple oppression based on the oppression of internal-community based Adivasi, Dalit Bahujan women’s selves within their community and outside – the larger caste based polity, perpetuates the hiatus between “the social” and “the political” in the spirit/system of democracy.

While opposition to globalization has grown in many contexts, there have been critiques raised whether the anti-globalisation, social movements across the globe are actually inclusive. Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujan communities in general and Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujan girls/women in particular have to reposition themselves within the such global, social movements through producing succinct alternatives that are critical as well as contemporary in nature.

Photograph by Thenmozhi Soundararajan. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons License Attribution Share Alike.

Design has developed as one of the core arena of knowledge. An innovative approach can be tailored through channelising the creative energy of Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujan girls/women into that of new media design thinking/practice. Dalit-Adivasi-Bahujan social/political assertions attain new dimension through the creation of counter online sphere to the conservative-caste blind “isms” in India. Internationalisation of their claim to private/public sphere has renewed the question of modernity related to these girls/women of change.

However, some questions remain silent. Can autonomy that they are denied due to Brahmanic and internal patriarchy be achieved through gender neutral techno realm? Can social justice of such groups of girls and women be derived through the theoretical constructions based on caste-gendered social locations and technology? Whether politically conscious Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujan women will be able to challenge the merit mongering, protean projection of Indian sisteriarchy that has strengthened its oppressive tentacles in the exclusive terrains of feminism, science and technology, politics and so on.

Indian feminist-politics of citation has created certain centers and margins while engaging with Advasi-Dalit-Bahujan politics. In other words, it systematically appeases or ignores the epochal, Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujan feminist interventions. Online sphere of Adivasi-Dalit-Bahujan feminist politics thus have the unique and autonomous arena of political sensibility. One of the central facet of the aforementioned online forums represent renewed understanding on the roots and alternatives related with caste-gender-patriarchy-religion- linked forms of oppression and resistance.

Footnotes:

- DN (2001) ‘ICTs in rural poverty alleviation’, Economic and Political Weekly, pp.917-920

- Zyskowski, Kathryn(2017) ‘Digital India’-a double edged sword’, Business Line, 5th July, 2017

- Dean, Jodi (2009) Democracy and Other Neoliberal Fantasies: Communicative Capitalism and Left Poli-tics, Durham NC:Duke University Press.

Dr. Smita M. Patil is currently an Assistant Professor in School of Gender & Development Studies, IGNOU, New Delhi, India. She earned her M.Phil and PhD from Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her areas of interest are women’s and gender studies, gender and law, political theory, social theory, caste, gender, identity politics, education and so on.

Featured Image Credit: Collage of campaign material from Dalit Women Fight, Savari, Documents of Dalit Discrimination and All India Dalit Mahila Adhikar Manch

Disclaimer: This article was originally published on GenderIT.org and has been re-published with permission.

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.