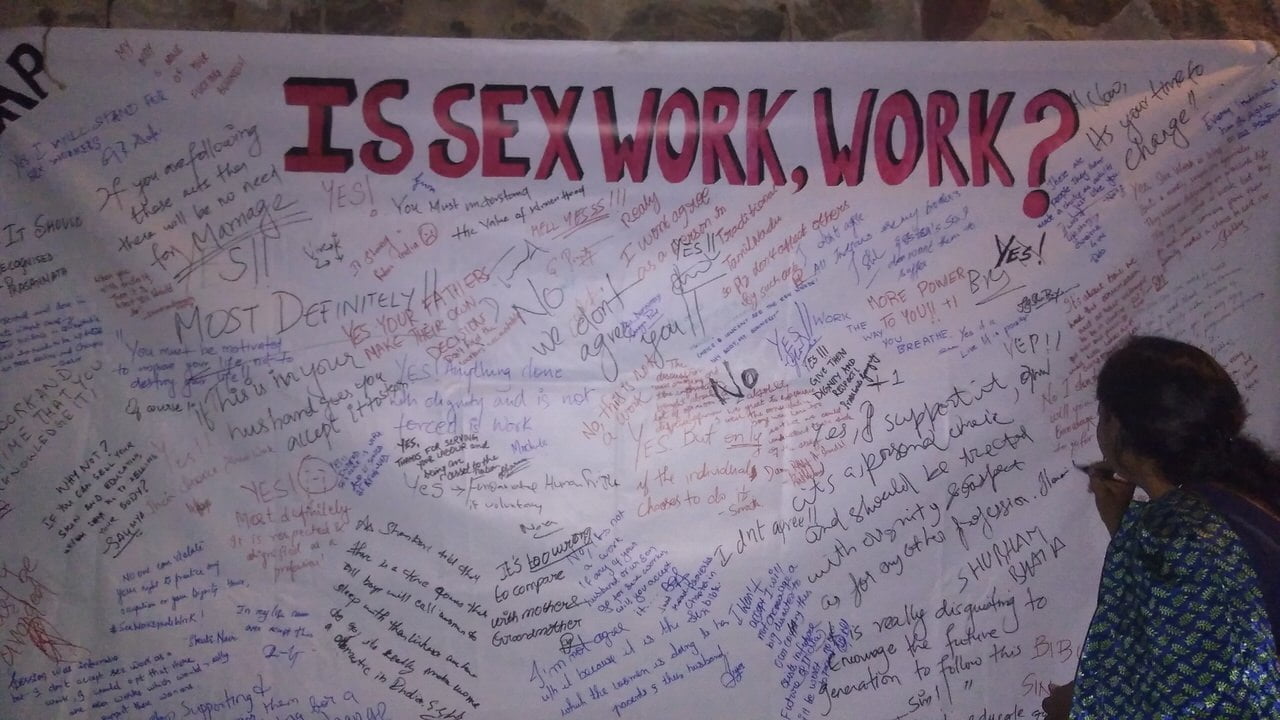

A panel discussion on sex work as work (labour) was organised by South India AIDS Action Program (SIAAP) on September 23 in Chennai. The discussion was semi-structured and saw overwhelming participation, and engaged the audience in dialogue along with the panelists. The panel included Dr. Ashley Tellis, Dr Kalpana K., Ms. Shyamala Natraj, Ms Asma Menon and six women and transwomen who engaged in sex work. The panel shared their opinions and answered questions at the open discussion after.

Dr Tellis set the stage for the discussion by broadly locating what was missing in the ongoing discussions regarding sex work, especially in the current legal framework – the voices of the sex workers themselves. He drew a distinction between trafficked sex workers and voluntary sex workers. The latter has being denied recognition by laws on sex work and hence left them vulnerable to oppression and violence.What makes it difficult for sex work to gain recognition as real labour is the idea of morality linked to the profession. He pointed out that the laws meant to ‘protect’ the interest of those engaged in sex work, actually infantilise women, leave their voices unheard and consider them devoid of any autonomy or agency. He goes on to define four clear areas of public debate- the question of choice of sex workers, the exploitation argument, the question of morality linked to sex work and the inherent idea of contradiction in sexuality.

He explained that all professions in a capitalist system are oppressive and exploitative and there is nothing in particular that makes the exploitation in sex work different from any other form of exploitation that other workers generally face. What makes it difficult for sex work to gain recognition as real labour is the idea of morality linked to the profession. The idea of negotiating pleasure with livelihood is unacceptable by the current society and the inherent contradictions and repression of desire and sexuality all contribute to sex work not being recognised as work.

Also Read: Why Is Sex Work Not Seen As Work? – Part 1

Ms. Natraj followed up with the idea that there were different stages in sex work itself. She defined stage one as the pre-entry stage where the sex worker faced discomfort, shame, guilt and uncertainty even if she or he voluntarily decides to engage with it. This stage bleeds into stage two which is right after entry where the uncertainty still lingers and there is fear – of the system, the police, society. Stage three is when sex workers have higher control, acceptance and active participation in their lives. There is a greater sense of autonomy and a greater sense of self. She then talks about stage four, where people generally decide to stop engaging in sex work – due to age, longevity of the profession etc.

She explains that prevention, rehabilitation and rescue operations in the current legal frameworks take place in stage three – due to greater visibility of sex workers in that stage. However, she argues that these legal interventions at stage three actually override the agency of the sex workers themselves who have greater control and desire to pursue the profession. Prevention programs might be more effective in stage one, rescue operations in stage two when the workers are still uncertain if they want to continue, and rehabilitation programs are essential in stage four when the sex workers are unable to continue working and have to deal with a sense of emotional and economic instability and uncertainty. She makes an interesting observation about how it is only women and transwomen sex workers who are subjected to these raid and rescue operations, and not men.

Asma Menon carried forward the discussion by stating that the root of the problem is the way the society looks at sex itself. It is scared of women having desires. It would prefer to view women as victims than adult subjects with agency. The reason why it does not recognise sex work as work is that this does not leave them with any legal protection that other workers have. This also results in them not having a recourse if their rights are violated and ensures that they are pushed into victimhood. She also spoke about the idea of consent within sex work. At this, Ms. Natraj interjected adding that since heterosexual women have no consent once they are married, in the current legal framework; this has deeper implications on not recognising sex work as work.

What makes it difficult for sex work to gain recognition as real labour is the idea of morality linked to the profession.

What made this panel discussion different of many others was that the voices of the marginalised group, in this context, the voices of the sex workers had a platform. They shared their experiences of being a part of the profession and gave their opinion on sex work as work. They seemed to have a broad consensus about enjoying their work and being comfortable about their profession. One of them said she had ‘saved enough money to buy jewellery’, something she could not envision doing before she joined sex work. One of the sex workers declared that she ‘identifies her body as capital’, and sees herself as just another worker, who deserves recognition and remuneration. The ‘denial of her performed labour is unacceptable’ to her. Another sex worker says that her dreams for her children are the same as other parents. She wants her ‘sex-worker-mother’ status to be duly recognised. She wants to be seen as a worker and not a victim. She ends her address by proclaiming ‘My body, My business’.

The question round which turned out to be a free-flowing discussion among the audience members and the panellists discussed many aspects of the issue. The idea of having a fixed red-light area was raised by an audience member, to which a sex worker agreed with and thought would be a safe space. However, another sex worker replied pointing out that it could potentially lead to further ghettoization and stigmatization. The idea of exploitation being a part of the capitalist system was discussed at length where the panellists urged the audience members to rethink why they believed that the exploitation in sex work was more unacceptable than other workers.

This lead to a long discussion about how the society views sex as ‘immoral’ and hence sex work as ‘dirty’. The audience was divided here with one section of the audience bringing up the culture argument and trying to reason out why anyone would voluntarily choose sex-work. The other half of the audience held the belief that sex-work was like any other profession and that the stigma associated was entirely due to the society’s fear of sex itself. Ms. Asma Menon added here that ‘Due to our circumstances, some of us choose to sell our education; some of us choose to sell our bodies.’

Dr Kalpana summarised the discussion and put forth her opinions on the issue at the end of the open discussion. She began by acknowledging that it was important to put the sex worker’s agency back into the centre of the discussion. She also asked the audience members to consider the historical construction of the marginalised position of the sex workers, where the bourgeois scientists in European nations portrayed sex workers as the carrier of diseases and pitted them against the bourgeois housewives and daughters.

The discourse on sex workers is marred with class and gender violence with makes the framework problematic in itself. The binary that has been created between the sex worker and the housewife makes sure that both are stuck in a cycle of oppression. The stigmatization of the sex worker contributes to the tyranny the housewife faces.

Also Read: Why Is Sex Work Not Work? Lessons Learned From Sex Workers’ Rights Movement – Part 2

About the author(s)

Sunaina Bose is a theatre enthusiast, pop culture junkie and an Austenmanic. In her free time (also when she’s procrastinating) she loves to take life changing quizzes like ‘What kind of pizza are you’.