“What is a Playboy?: “Is he simply a wastrel, a ne’er-do-well, a fashionable bum? Far from it: He can be a sharp-minded young business executive, a worker in the arts, a university professor, an architect or engineer. He can be many things, providing he possesses a certain point of view. He must see life not as a vale of tears but as a happy time; he must take joy in his work, without regarding it as the end and all of living; he must be an alert man, an aware man, a man of taste, a man sensitive to pleasure, a man who—without acquiring the stigma of the voluptuary or dilettante—can live life to the hilt. This is the sort of man we mean when we use the word Playboy”

–The Playboy Philosophy by Hugh Hefner

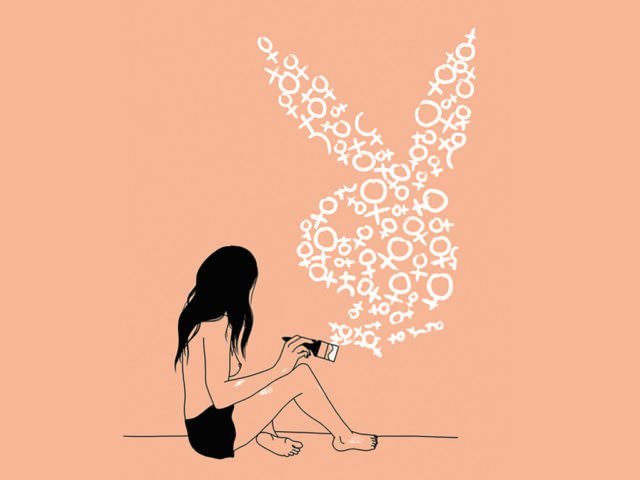

When Hugh Hefner died last week, for a man who made a career out of sexual exploitation and objectification, the praise he received was mostly unanimous and pretty effusive. Is our cultural memory so warped that we can posthumously glorify a media mogul for his achievements in soft porn?

Many women had come forward citing the poor pay, their sexual exploitation and overall terrible work practices, de-glamourising the status of being a ‘bunny’, but tributes came pouring in from prominent women, grateful and grieving. What exactly are we mourning when we are talking of a man who built a playboy mansion with ‘bunnies’? Could it be the modern intellectual’s unquenchable need to appear broadminded and ‘open’? Or perhaps in our catastrophic age, it is because we rely on nostalgia, and Hugh Hefner is a cultural icon for our ever new world.

If cultural icons are celebrated and revered for their unique contributions to the cultural and social life of a country, is this remembrance only an acknowledgment of Hugh Hefner’s reach? Porn has become such a ubiquitous part of modern life that to debate its value seems anachronistic. The biggest trap of an evaluation of Hefner and his magazine is that any criticism is morality. When it comes to sex, morality is eminently unfashionable and a domain reserved for the elderly or the Catholic.

If not through morality, how do we take stock of the women in Playboy? Is feminism coming in the way of sexual liberation and revolution? Since the 60s, sexual revolution has undergone a conceptual whittling down, and Herbert Marcuse would certainly find the role of capitalism in the sexual freedom of our contemporary world very disconcerting. Feminism is a useful project to uncover the links between sex and capitalism, and can help in understanding the Playboy culture through a lens that is not decidedly moral.

What exactly are we mourning when we are talking of a man who built a playboy mansion with ‘bunnies’?

In the quote above from ‘The Playboy Philosophy’, Hefner theorizes an ideal way of life, and the ideal reader, who can live ‘life to the hilt’, and certainly Hefner embodied this credo: with his modernized harem (the Playboy mansion), groups of bunnies, and a young wife. He was always eager to make synonymous Playboy and a kind of sexual carpe diem (seize the day).

Constantly touted as the ‘new generation’ with its newer views on sex, Hefner fashioned himself as a ‘young man at heart’ who did not have patience for old men’s moral disgust. Instead of being embarrassed at the naked pictures, he argued that we needed to overcome an ingrained conformity and puritanism. This led him to embrace charges of ‘irresponsibility’ or cause for ‘decline of western world’, because for Hefner, this hedonism was a celebration not a calculative exploitation of women.

Certainly many things have become normalised over years. You may choose to engage with an exploitative profession like pornography voluntarily for money or intellectually like Stoya. Can we then accept chauvinism as diversity within such a plurality of erotics? The Playboy Philosophy is very honest in its objectives, and declares openly that it is marketed towards the ‘urban male’, ‘who naturally has a little more interest in sex and pretty girls than does a general and family audience’.

The heart of Playboy is its bunnies. The urban male is treated with simulations and variations of the seductive but playful female. But as Hefner is quick to point out, nudity and obscenity are not synonymous, and he is celebrating ‘God’s handiwork’ and the human body against the outdated telos of sexual repression.

Playboy did not celebrate the woman’s body; it exploited it.

Yet Playboy services the most normative gendered relationship in our world – heterosexuality, and reinforces patriarchy. Hefner’s hedonism is problematic not just because it is so overtly heterosexual, but also because it revels in male pleasure. This male pleasure continues to revolve around the objectification of women. This objectification begins and ends with sex and sexiness of the woman for the man. In its proliferation of such stereotypes, and for making them a very marketable consumer product, can we forgive Mr Hefner?

Hefner may be commended for his gonzo journalism but let us not celebrate him as a man who sexually liberated us. For most Marxists such as Marcuse, a sexual revolution had the power to transform and begin a social revolution. For Marcuse, the establishment controls and maintains existing power relations through repression, and a ‘political radicalism’ could only be brought about by a ‘moral radicalism’.

But what Hefner didn’t understand is that Marcuse’s sexual liberation was premised on subverting the consumer economy and its foundational relation between domination and exploitation. Playboy did not celebrate the woman’s body; it exploited it. It upheld perfect figures with perfect stats and publicized a specific type of woman for the consumption of a specific kind of man. That may have helped the young ‘urban male’, but it most certainly didn’t help women.

It is natural to rhetorically ask what the big problem is if the bunnies didn’t mind. In the 1963, Gloria Steinem wrote A Bunny’s Tale, documenting her life as a playboy bunny for a month and recording the poor working conditions. The power of such personal narratives is the interpretation, and that is the role of feminism vis-a-vis the woman’s body. It is on interpretation that our meanings of exploitation and objectification reside. Steinem was able to show how women followed strict codes for men, and that far from sexual freedom, it was a sexual mode that pleased men. A sexual revolution may be taboo or vanilla, but it will be, more than anything, equal.

Also Read: Hugh Hefner, And The World He Left Behind

Featured Image Credit: Playboy