We scroll media handles, flip newspapers to sneak-peek glamorized food avatars of what our famous celebrities eat – chappati count, protein portions, oil profiles, perfect water checks to sincerely-hyped exercise regimes from pilates to power yoga and emulate them in various capacities. Contrary to life and practice, meeting these positive bunch of women renewed several notions of stamina, work and how just-a-food-carrying business can be much more than its contents.

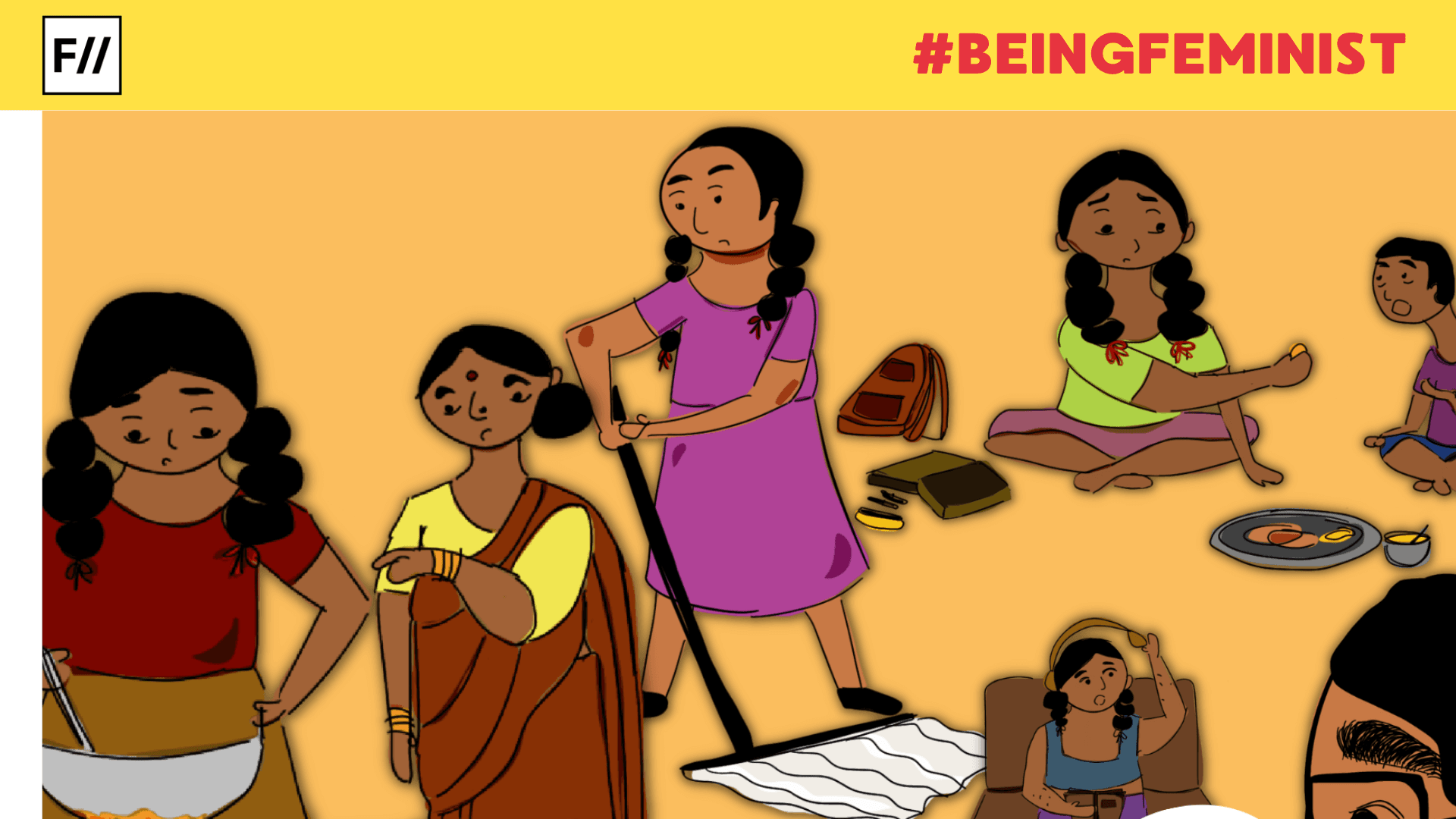

The concept of women bringing ‘dabbas’ for men at work in the fields is the most typical stereotype we have been picturing for years. Also, the term brings to mind the famous dabbawalas from Mumbai known for their lunch delivery services. Well, the current climate is perfectly timed for changing this stereotype. The picture shows rice field workers that are mostly women. They set out early after completing everyday chores and packing food for themselves.

The lunch box is imperative of one’s quality of work, based on region, economy and practice. Sparkling aluminum round containers with lesser used handles, well-balanced by a speeding group of women is a regular sighting during the harvest season in Bengal. Intriguing as they seem, it was the process of rice cultivation that had brought me to the fields in the first place. “Rains have been bad, most of our efforts of throwing the chara (seeds) has been wasted due to flooding in many areas. But we have started again. It takes all day, so food is a must for us to carry.”

“Men need us after initial preparation of a fertile plot by ploughing and tilling the land. We are good in fieldwork that requires seeds to be thrown in a horizontal fashion”, as questions on cultivation practices (planned in my head) were halted with their enthusiasm. With research suggesting 43% of the female workforce is in the agricultural sector globally, facts present a much-mightier story. The same study mentions how the overall labor burden of rural women exceeds that of men, and includes a higher proportion of unpaid household responsibilities related to preparing food and collecting fuel and water.

Their average allowances range from 60 to 150 rupees per day as compared to men who make 250 to 500 rupees a day, perhaps more depending on their nature of work. They were surprised when asked about accepting unequal pay. “Are you proposing we should ask for more? Our employers are Babus (men) – they can get many others for the same pay.” However they did understand equality in their own way – with references to men bringing them to the work-fields; but still having housework to tackle as well.

Also Read: Unpaid Domestic Labour And The Invisibilisation Of Women’s Work

“Come have a meal”, was the obvious invitation as they could gauge my curiosity for their dabbas. Generosity spilled over with happiness when discussing their choice of tiffin-boxes with a form of high spiritedness. “They are cheaper than steel, spacious and can carry the appetite we have”. Another one went ahead, smiling, “Our day starts at 4 in the morning when we cook for the entire family and then leave for the fields”. These have handles, which makes them easier to hold for they need to travel for long distances on foot.

The mysterious dabbas carried lunch, which had a systemic pattern:

Firstly, everyone had rice, but the difference lay in their method of preparation which involved slow cooking over either charcoal or wood. The rice is mostly unpolished with big grains and has a close proximity to brown rice. It is half-boiled, cooked three-fourths, with starch left unstrained that soaks in the remaining moisture when left for few hours.

The rice takes time to chew. The liquid consistency of the cereal makes one feel full and not go hungry for hours. Some of the women said that rice is easier to cook than chapatti, cheapest in bulk and can be prepared at once for the family, saving time.

A few additions follow, some of them dunk potatoes in the pot at the time they boil rice so they have boiled potatoes that go well with rice. Salt has been already sprinkled from home. The potatoes retain their skin and absorb the flavours of slow cooked rice. One woman prefers a stir-fried vegetable which has potatoes and bitter-gourd tossed in salt and turmeric.

The love for greens are indicated with sajne paata shaak (drumstick leaves), as they call in their local dialect. It grows in abundance near their houses. Slightly tempering them with dried red chilies is enough to retain it’s nutrients. The rice here is called panta-bhaat, with water poured in to keep the previous day’s cooked rice slightly fermented and is known for its stomach cooling properties.

Side dishes keep changing – a rice with boiled potatoes known as ‘Aloo sedho bhaat’ in Bengali had a drizzle of magic with a small portion of sautéed green chilli in mustard oil.

Most dabbas carry potatoes of some kind, the last one has the famous aloo bhaja (potato finger fries) in mustard oil, with panchoran, a seed mix of five: fenugreek (methi), cumin (jeera), fennel (saunf), nigella (kalaunji), black mustard (rae), in equal proportions. A green leafy vegetable, radish leaves (shaak) is a common accompaniment. In this heart-warming, not-so-elaborate turf-spread, one notices missing elements like pulses or any form of protein, but these women survive on their staple of carbohydrates.

Women’s nutrition is a residual reflection of what she cooks for the family. The pulses, chicken, fish, and even milk and dairy if available, or cooked in any form, are left for male members and their children as they consider them the ones who need them more. The process of cooking food and nourishment can also be premised in the fight for equality.

Also Read: In Photos: Indigenous Women Who Pass Down Land To Their Daughters

Sneha Rout is a development professional with National Health Mission with an appetite for stories that sketch ethereal society, sharpen instinctive environments and trace lost legislative blueprints. Mile-posting facts on gender, malnutrition and public health issues that fits in her wayfarer’s knapsack.