Feminism is often categorized as ‘waves’ – time periods aimed at elevating women’s status in society and giving them equal rights. This metaphor describes the surge of activity at the beginning of a phase, which then reaches its peak, usually in the form of a concrete accomplishment and consequence of struggle.

The ‘wave’ then falls and lapses till another ‘wave’ forms. This classification helps us differentiate between movements with varied purposes and characteristics and create a broad timeline of the progression of feminism.

This narrative places the beginning and nucleus of the movement in the West. For the purpose of this article, I will trace the first wave in reference to the USA while acknowledging the contributions by early feminists all around the globe.

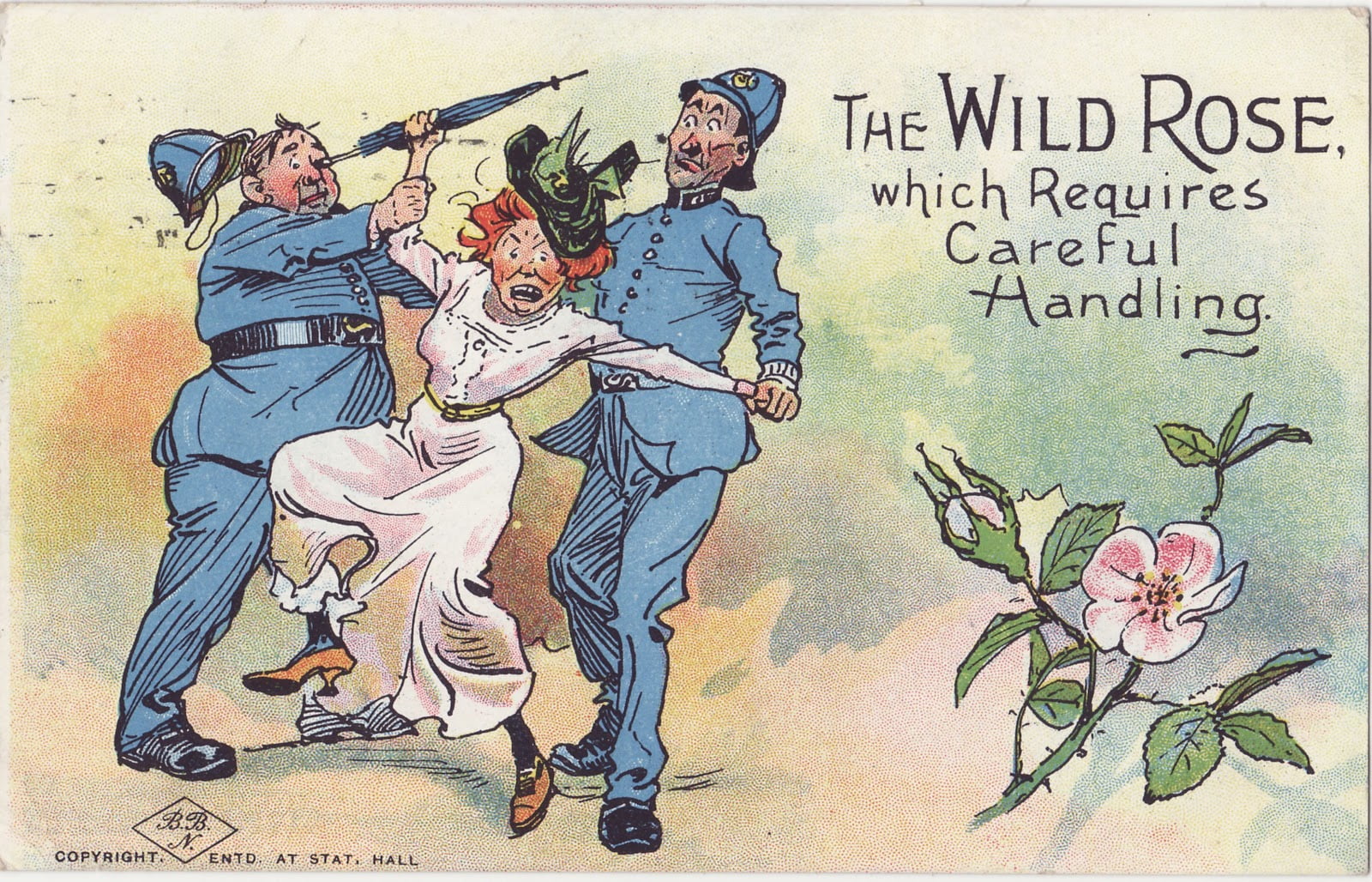

The first wave of feminism generally refers to the nineteenth and early twentieth century in the western world. This phase revolved largely around gaining basic legal rights for women that today we cannot imagine reality without. Politics and business were completely dominated by powerful men who didn’t consider women capable enough to be a threat.

Women were confined to their households and didn’t retain any control there as well. Unmarried women were seen as the property of their fathers, and married women the property of their husbands. They didn’t have the ability to file for divorce or be granted custody of their children.

Marital rape as a concept was unheard of because it would require treating women as individuals with the power to make their own choices. Women who did work held low positions such as secretaries and worked largely in factories managed and controlled by men. As they had no right to vote in elections, calling them second-class citizens was an understatement.

The first wave was connected with the abolitionist movement in the USA at the time. Both the movements aimed at social reformation and liberation from oppression. The former from the patriarchy and the latter from racial bias. An example that reveals the extent of this link lies within the origins of the first wave itself.

The wave is often demarcated as officially beginning with the signing of the ‘Declaration of Sentiments’ at the Seneca Falls Convention, the first ever women’s rights convention. The convention was created when Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott were denied seating at the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. Many abolitionists were also feminists and thus the anti-slavery movement fueled the first wave and vice versa.

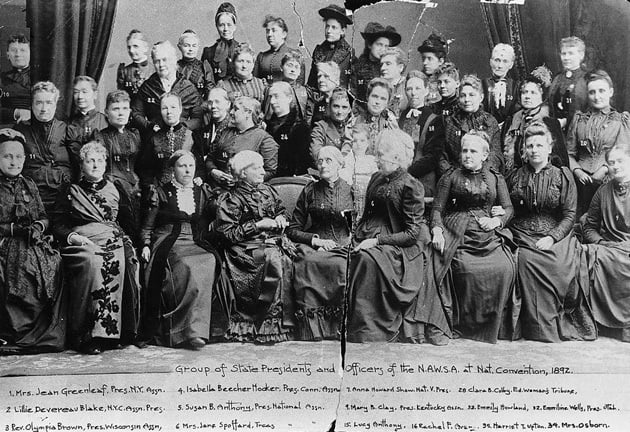

Suffrage, the right of women to vote in elections, became the goal of the movement with the formation of the American Equal Rights Association in 1866. When this organization collapsed, the National Women Suffrage Association (NWSA) was formed in early 1869. The American Women Suffrage Association (AWSA) formed later that year.

The solely female-led NWSA had a broad program and wanted to work towards the overall upliftment of women in society on the national stage whereas the AWSA focused on gaining the essential right to vote through state amendments. This divide led to a split in the movement, with little advancements made towards the Suffragist goal while significant improvements in higher education for women took place.

As the methods of the two bodies grew more alike over the years, they eventually merged into the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). In 1869, Wyoming became the first state to grant suffrage to women.

An unexpected source of support for the movement came from the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1876, which advocated against the sale and consumption of alcohol. Members believed that allowing women greater entry into the public sphere would allow them to exercise a positive influence on the world. They thought women were morally superior and could become “citizen-mothers,” reinforcing the stereotype that a woman’s purpose was to be a mother and caretaker.

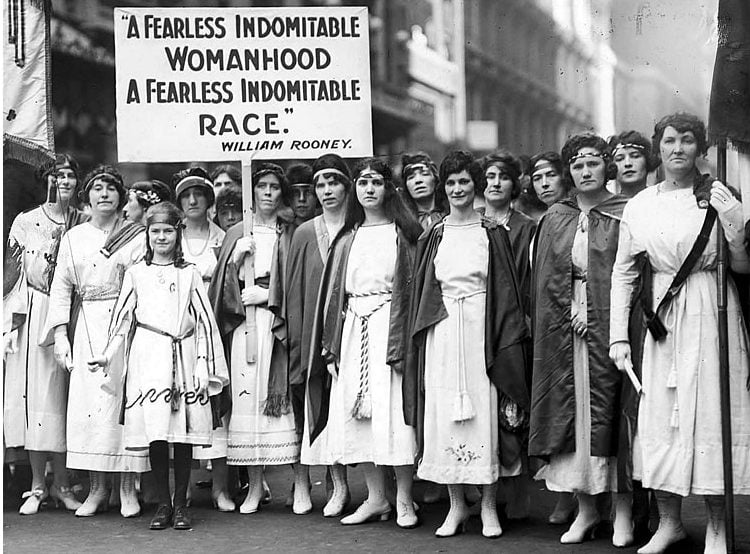

In 1916, the National Woman’s Party (NWP) was formed by young feminist Alice Paul by breaking from NAWSA and aiming to achieve suffrage by working towards a constitutional amendment instead of state amendments. Inspired by British militant suffragists, the party staged demonstrations outside the White House and continued their campaign through the World War.

Also Read: The History Of ‘Hysteria’ And How Science Can Be Sexist

Members were arrested, went on hunger strikes, carried out picketing and used publicity to generate pressure on the Wilson administration in favour of suffrage. While they tried to refocus attention on the movement during the World War, the President of NAWSA supported the US’s war effort, thus positioning NAWSA as a patriotic organization.

This became useful when lobbying in favour of the Nineteenth Amendment and its ratification by all states. The Amendment declared, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” Despite resistance from Southern Democrats, it passed in the Senate on 4th June 1919 and was ratified last by Tennessee on 18th August 1920.

In the common narrative of the Suffragist Movement, the first wave of feminism ends with this Amendment. This in itself shows the selective and exclusive nature of the movement. Women of colour were still practically disenfranchised, and the victory was only for white women. Black women were stopped from exercising their right to vote through tedious disenfranchisement tactics, facing bodily harm and even arrest.

The first wave had marginalized black women, who faced discrimination based on race as well as gender. While the NWSA initially worked towards suffrage for white and black women, with the entry of younger feminists into the organization, the goal became white-centric.

Also Read: Suffragette And Princess Sophia Duleep Singh: Stranger To Fear | #IndianWomenInHistory

Members saw the support of black women as a liability, which was a hindrance to their cause. Due to widespread racism, especially in the southern states, white women were afraid of letting black women gain political power. With this increase in exclusion, black women formed separate organizations to work towards black suffrage.

The National Association of Colored Women (NACW) was founded in 1896 and the Alpha Suffrage Club founded in 1913 were some of the first bodies which fought for black suffrage and raised awareness amongst black communities. An argument used in support of white female suffrage was that of the “educated voter”.

White women campaigning in favour of suffrage claimed that their education and political awareness would make them good voters and allow them to make informed decisions. Black women, who didn’t have access to similar higher education could not stand behind this and became even more marginalized in the movement. When the case in favour of suffrage did not make space for the circumstances faced by black women, they could not share in the triumph of the Nineteenth Amendment.

Another group whose contributions are ignored is the Asian community in the US at the time.

Foreign-born Asians were not allowed to become US citizens, irrespective of how long they had resided in the US, and thus couldn’t vote. This didn’t mean that there were no contributions by Asians in the first wave.

In Portland, Oregon, 7 Chinese women attended a banquet of more than a hundred suffragists. There was also an organization for local equal suffrage for Chinese women run by S. K. Chan, a local physician. Another Asian member of the Suffrage Movement was Mabel Lee, the first Chinese woman to graduate with a PhD from Columbia University.

She was a staunch advocate for women’s right to vote and led a Chinese American contingent in a 1917 pro-suffrage parade in New York City. However, when the Nineteenth Amendment passed, she couldn’t vote due to the disenfranchisement of Asian women being carried out.

While the first wave lacked inclusivity, it gave the world some of the fiercest and most dedicated feminists who inspired the women around and after them. Susan B. Anthony, an abolitionist and renowned suffragist was an invaluable leader of the movement. She campaigned for black suffrage, published the periodical, The Revolutionary, was President of NAWSA till the age of 80, resisted abuse and judgement and upheld her beliefs.

She cast a vote in the 1872 Presidential Election in protest for suffrage and was promptly arrested and charged a fine, which she refused to pay. Undeterred by the backlash, she lobbied in Congress in favour of suffrage and when the Nineteenth Amendment passed 14 years after her death, it was commonly called the Susan B Anthony Amendment.

A champion of black women’s right to vote and the abolitionist movement was Sojourner Truth, a former slave who had become a preacher in the 1830s. She was charismatic and articulate and is remembered for her speech Ain’t I A Woman which she gave at a women’s rights conference when the discussion revolved only around white women.

She said, “That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman?” She successfully points out the double standard existing within the movement at that time and was a voice for the black women who felt unrepresented.

The first wave of feminism set the stage for the second, which had a more expansive purview and extended the struggle for equality to other sections of society. It’s white-centric nature led to the extreme marginalization of black women in the feminist movement, a problem that arose again years later in the second wave.

As feminism became more fleshed out and developed as a concept, feminists often took the achievements of the first wave for granted. First wave feminists were viewed as stuffy and part of a narrow-minded older generation. Despite its faults, the first wave lay the groundwork for future feminists and played a vital role in giving women basic legal rights.

Read the second part here: A Brief Summary Of The Second Wave Of Feminism and the third part here: A Brief Summary Of The Third Wave Of Feminism.

Also read in Hindi: नारीवाद का प्रथम चरण : ‘फर्स्ट वेव ऑफ फेमिनिज़म’ का इतिहास

Featured Image Credit: Wikipedia

About the author(s)

A student at Ashoka University, Tara loves poetry, impassioned conversation and brewing warm cups of tea.

There is a mistake in this text:

“A champion of black women’s right to vote and the abolitionist movement was Sojourner Truth, a former slave who had become a preacher in the 1930s” – the right time period is in the 1830s.