For centuries, society has dictated women’s choices over their appearance, by telling them how to dress and be ‘ladylike’. As a direct result of this normalized instruction, women have internalized the misogynistic idea that in order to be seen as presentable, they must self-edit and self-harm.

Exerting dominance over a woman by asserting the unrealistic beauty standards she must attain is just one of the many ways in which patriarchy, globally, has been oppressing women. For instance, the Chinese had a tradition of foot-binding, or ‘lotus-feet’, which persisted for almost 8 centuries. The arches of women’s feet were systematically broken and reshaped by forcing them to wear tiny ‘lotus-shoes’ that didn’t allow their feet to grow beyond 3-4 inches. The smaller the feet, the higher the chances of marriage, as small feet were seen as a status symbol for the elite.

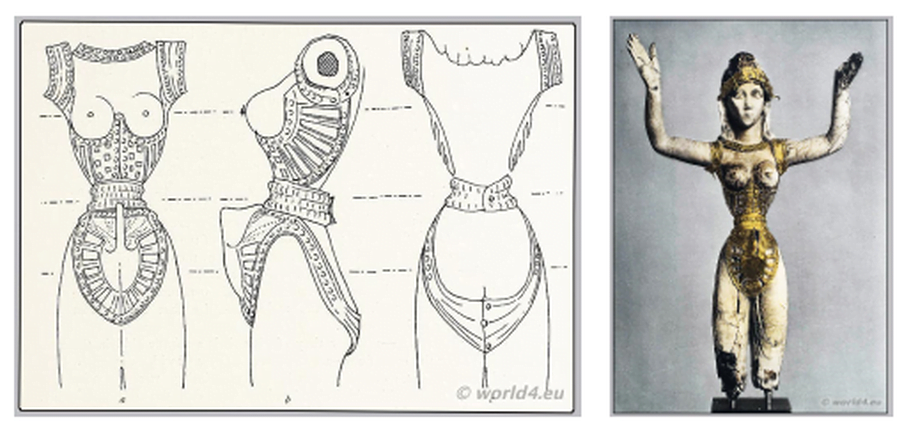

At the same time in Europe, corsets and other equivalent pieces of clothing, that sought to restrict the growth of the waist, were popular, as small waists were seen as the epitome of femininity and female refinement. Even today, there are a plethora of examples all around us which illustrate how society takes it upon itself to decide the ‘appropriate’ look for a woman, and judge how she fares on a scale of expected femininity by attaching ‘positives’ and ‘negatives’ to aspects of her appearance.

The length of her clothes (leading to the atrocious question of how ‘revealing’ they are), the colour of her hair (‘boldly’ coloured short hair may indicate that she is ‘rebellious’ or ‘promiscuous’), the number and locations of her piercings, etc., are all placed under society’s microscope of patriarchy.

Expecting a woman to get rid of all her visible body hair is just another example of how women are expected to conform to the societal perception of an ‘ideal’ image. While many women start removing body hair for social/normative reasons, they continue to do so to appear more feminine/attractive.

Body hair removal emerged as a survival tactic many millennia ago. With time, it was reduced to an aesthetic value, which then served as a foundation for the oppressive, modern and gendered notions of feminine hairlessness.

Older methods and ideas of body hair removal

Removal of body hair has a long and complex history, dating all the way back to The Stone Age, 100,000 years ago. Cavemen used flint blades, seashells and other sharp objects to shave off all body hair. Hair removal was done for practical reasons, such as to prevent frostbites (especially during the Ice Age, when the unending winter would make the water freeze on their body hair); not provide a breeding ground for parasites like mites and lice and to take away any advantage an adversary might get in a brawl by grabbing.

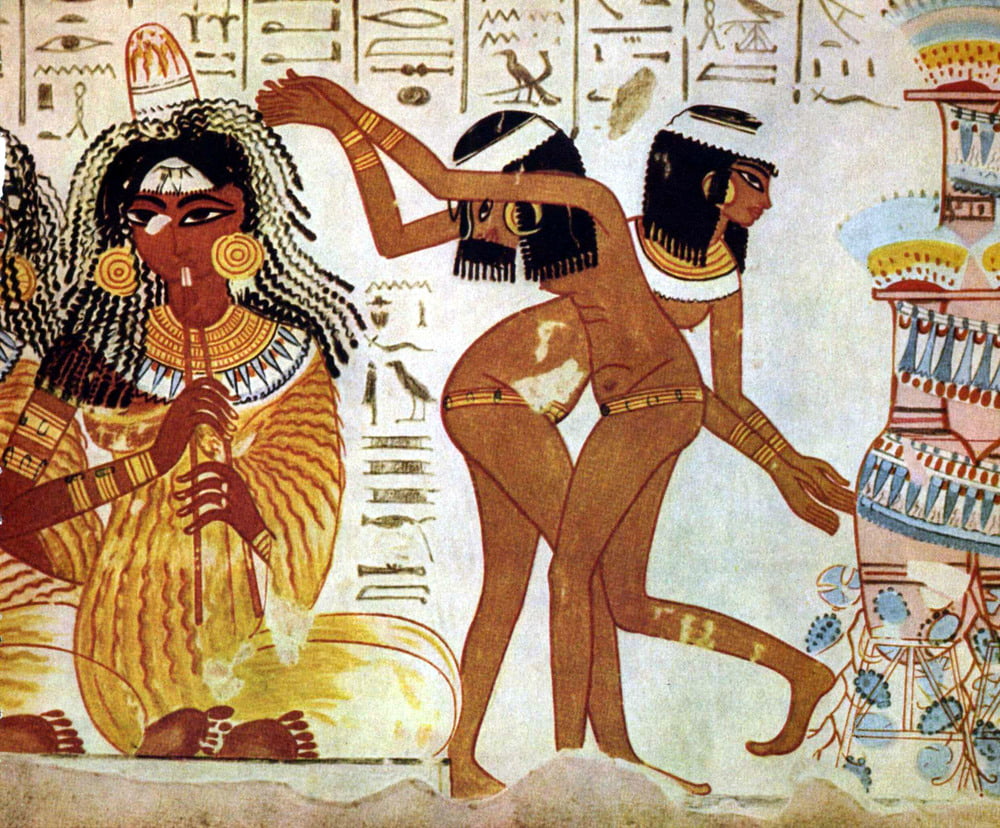

In Ancient Egypt (around 3000 B.C.), men and women were sticklers for cleanliness. They maintained a strict regiment of bathing and removing body hair; primarily because of the blistering heat that they lived in, but also because they believed that having body hair was an indicator of being ‘uncivilized’. Cleopatra, a trendsetter of her time, is one of the individuals to whom the creation of this beauty standard can be attributed. Thus, they used one of the many processes available at the time, such as ‘sugaring’, tweezers, shaving, a combination of depilatory creams (such as a mixture of burnt lotus leaf, tortoiseshell and hippo fat) and pumice stones, to remove all hair from their body, except for their eyebrows.

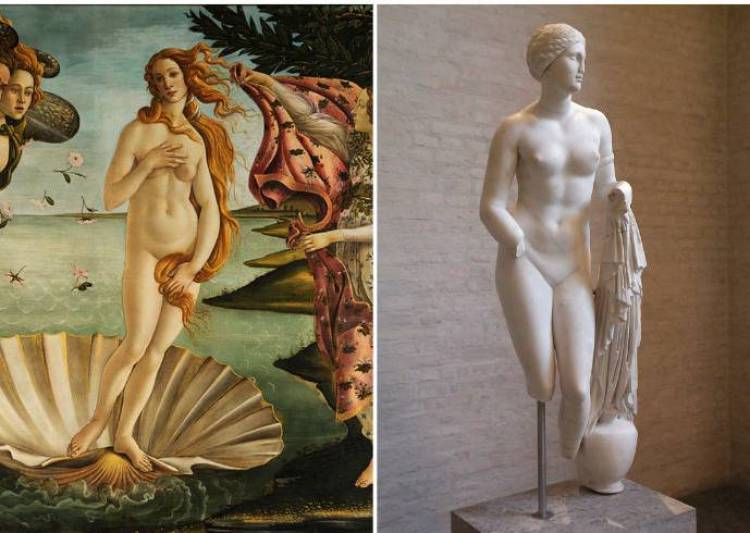

The Romans (around 400 B.C) too, like the Egyptians, viewed body hair as a class issue, wherein the amount of body hair was inversely proportional to one’s status in society. However, unlike the Egyptians, this norm was restricted only to women. The testament to this is that upper–class women in portraits and statues of divine beings were always hairless.

Queen Elizabeth formulated the norm for European women during her reign around the 1500s. She believed that hair on the face must be groomed at all times, requiring the eyebrows to be shaped and, hair on the forehead and upper-lip removed. Europeans developed a fashion of long foreheads, and in adherence, women would remove all hair from the forehead, and were encouraged to raise their hairlines by one inch. Mothers from wealthy families would rub walnut oil, and the less economically privileged would use bandages soaked in ammonia (which they obtained from their feline pets’ faeces) on their daughter’s foreheads to prevent hair growth. However, arm and leg hair did not matter, as clothes always covered them.

Also Read: The History Of ‘Hysteria’ And How Science Can Be Sexist

Therefore, hairlessness is a value that that has deep roots in many cultures all around the world. Historically, societal perceptions on ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘why’ regarding body hair removal differed. However, when modern notions of body hair entered the picture in the 1900s, the answers to these questions, globally, became more uniform.

Modern methods and ideas of body hair removal

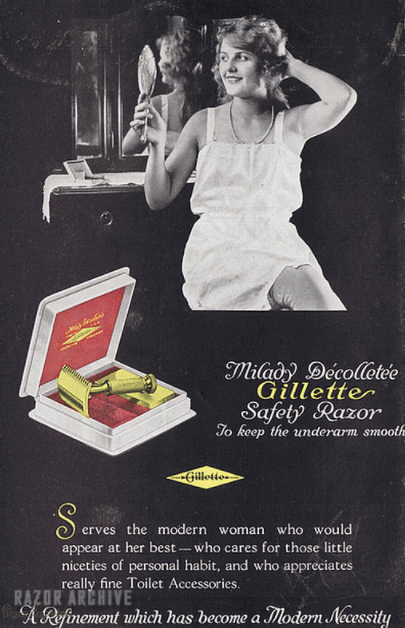

By 1900s, women started wearing sleeveless clothes that exposed more skin, and manufacturers of razors and depilatory creams wasted no time in capitalizing on this change in style of clothing. Gilette, the pioneer for women’s razors, marketed strategically so as to use its product to create the problem and provide a solution: to save women from the “embarrassing personal problem”.

In 1915, Gilette created the first ever razor especially for women, ‘Milady Décolletée’ which promised to remove the “humiliating growth of hair on face, neck and arms”. It referred to shaving as a “refinement that has become a modern necessity”, and to its product as “the dainty little Gilette used by the well-groomed woman to keep her underarm white and smooth”. Looking back, a century later, this proves to be a landmark year in the history of social norms related to women’s body hair.

Advertisements in magazines at the time sought to inform women of the changing fashion trends that demanded women to remove all visible body hair apart from that on the head, labelling it “superfluous”, “ugly”, “unwanted” and “unfashionable”. These advertisements marked the beginning of the ‘The Great Underarm Campaign’. 66% of the advertisements found in Harper’s Bazaar’s editions glorified shaving by the planned use of pictures, taglines and markedly increased the frequency of such messages.

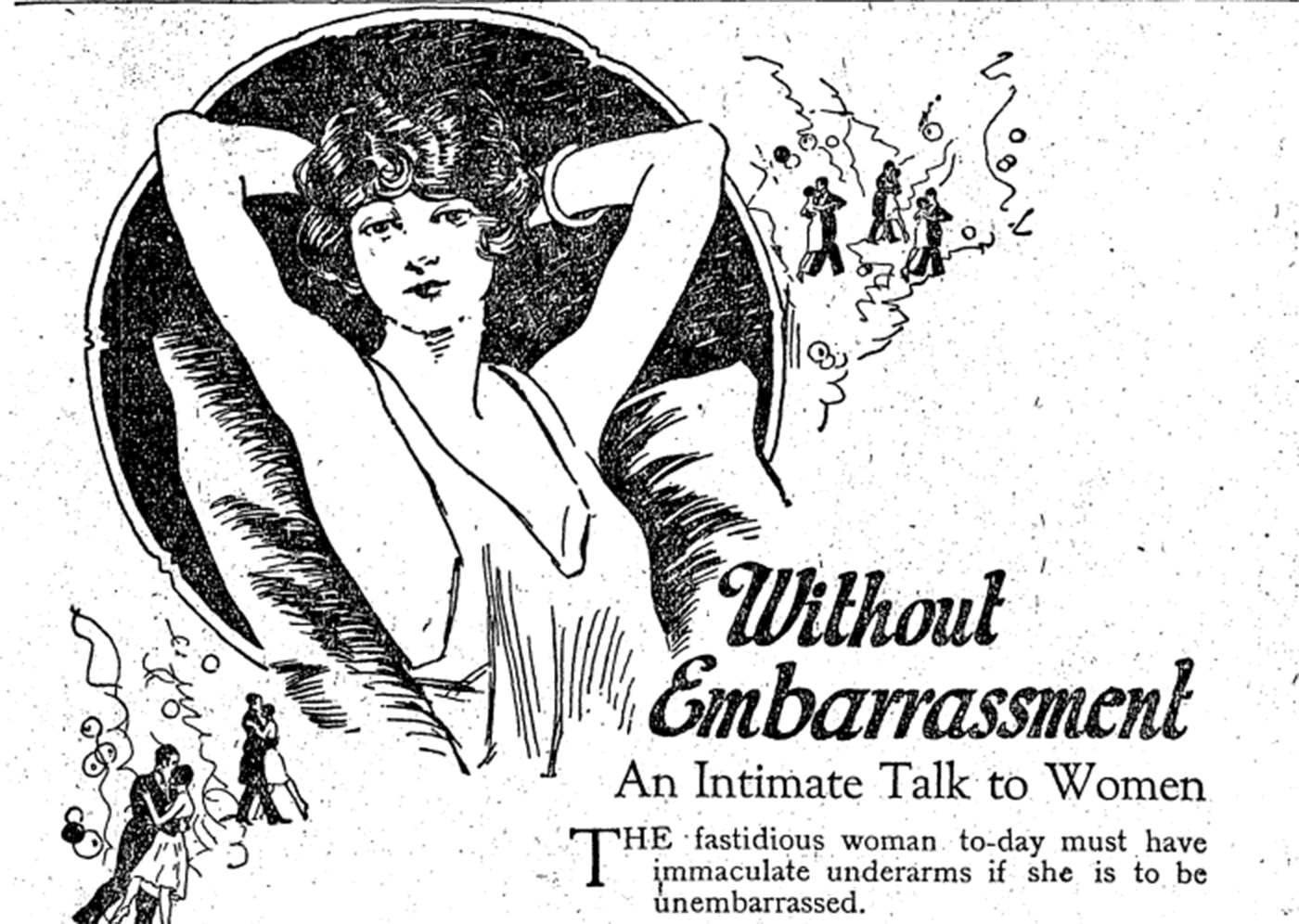

They showed women with bare arms and underarms raised above the head, accompanied with taglines such as “The fastidious woman today must have immaculate underarms if she is to be unembarrassed”; “Summer Dress and Modern Dancing combine to make it necessary to remove objectionable hair” and “If we were the dean of women, we would levy a demerit on every hairy leg on campus”.

McCall, a popular American magazine with a considerable readership, gave an advertisement accompanied with the tagline, “Let’s look at your legs – Everyone else does”. Life, another magazine gave another such advertisement, stating that in order to wear those sleeveless tops that had just come into vogue, “armpits must be smooth as your cheeks and sweet as your breath”.

A few more factors added to the normalization of hair removal. In the 1940s, World War II forced women to go out and work. However, due to the nylon shortage, they were forced to do so without pantyhose, thereby requiring them to bare their legs. Women were now imposed with the duty of ensuring their mates’ fidelity by keeping strict a check on their appearance.

Aided by changing fashion trends, skirts became shorter, silk stockings more prevalent and swimsuits more revealing. Manufacturers saw this as an opportunity and marketed even more aggressively for hair removal. Their advertisements encouraged women to abide by the ‘right’ look that was slender, sophisticated, youthful and sensual.

By the 1940s, women did not need to be convinced to remove hair – they had internalized the modern link between attractiveness, femininity and hairlessness. Rather than focusing on the practice itself, advertisements now emphasized on the superiority of their own product.

For instance, Remington came up with the first ever electric razor that was presented as a better alternative to manual shaving and depilatory creams that tended to irritate the skin. By the 1950s, society had accepted that a woman must be hairless in order to be truly feminine. Shaving had changed from being a freak story to the new normal. Waxing was introduced in the 1960s and electrolysis in the 1970s. With the increasing popularity of swimsuits in the 1960s, bikini hair removal gained momentum in the 1970s.

Thus, between 1940-1980, body hair removal crystalized as the norm in the USA. As a result of multiple factors such as increasing globalization, colonialism, ‘modernisation’ and Westernisation, the practice, slowly and gradually permeated into parts of the world as well.

Also Read: In Search Of The ‘Perfect’ Body

Joysheel is a 4th-year law student at O. P. Jindal Global University, interested in international law and gender studies.

The second part of this article engaging with the contemporary politics of body hair removal can be found here.

Featured Image: Pure Sugar