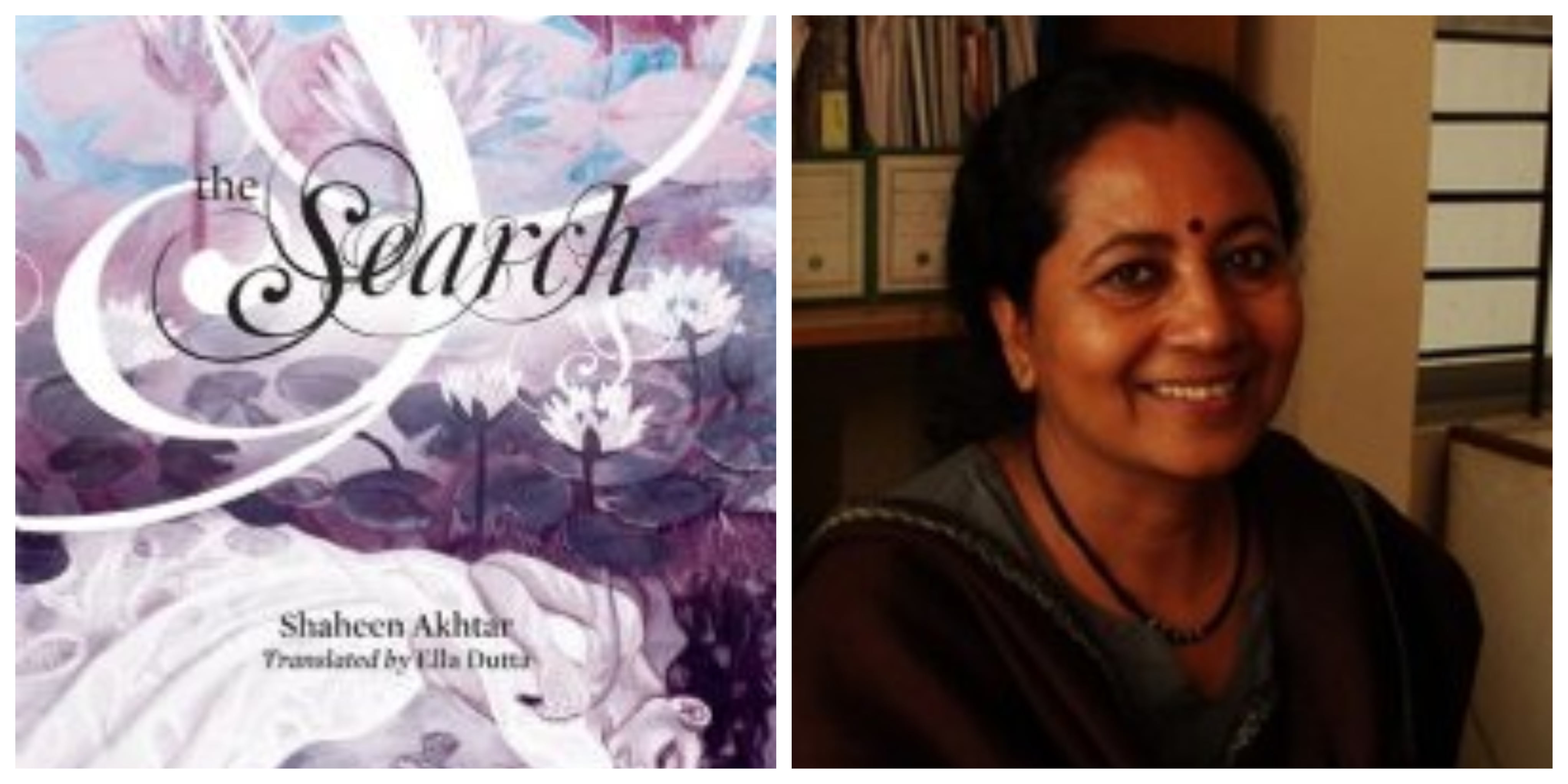

Talaash is the second novel of the Bangladeshi writer Shaheen Akhtar. It captures the brutalities of the 1971 war of liberation and its contingent afterlife — more specifically, the scars it has left on women. For thirty long years, Mariam, the protagonist of the novel, lives with memories of a war that refuses to end for her. The analeptic and proleptic shapings of Shaheen’s prose travel in and through those shattered memories (and their public use) to construct a devastating archive of pain and anguish, far beyond the pale of cause and effect. Shaheen Akhtar’s mesmerizing and moving novel, set against the background of the Bangladesh war of independence, explores the violence done to women, their courage and heartbreak, their search for love and their betrayal. Taalash (The Search) was awarded the Prothom Alo Literary Prize in 2004.

Moments of her past surface in Mariam’s mind like clumps of water hyacinth caught in the eddies of murky waters. This happens whenever someone asks about her life, or when Mariam, her mind and body becalmed like a still pond, recollects times gone by.

She was Mariam, Mary in other words. She remembers the moment: her body is stretched upwards, one hand reaching for the clothesline in the courtyard, the other hanging loosely by her side. One foot rests on a brick, the other is in the air – solid ground just three inches below. It is as if she is half suspended on the gallows, from where she watches Montu leave with tears in his eyes. Actually she does not see him. She hears the creak of the gate opening and knows that Montu has gone.

By the time she has fumbled along the rope, picked up the gamccha, blown her nose, wiped her eyes and looked up, Montu, her younger brother, has disappeared down the bend in the alley. Tears blur Mariam’s vision. She is momentarily blinded. She does not see or hear anything–except for the metallic sound of the gate. She does not know it then but this unseen, unheard moment holds in its womb a terrible explosion. Montu is lost forever in its smoky eruption.

Mariam survives with her body squeezed and pounded like meat in a mortar and pestle or with a life which is portioned out like the sacrificial flesh of the qurbani. After that moment, her body is never her own. She can never lay claim to her life again.

It is not just in times of war but in times without conflict, in times of peace, that a woman’s life is thought of as a four- wheeled vehicle, with the body as its driver. If the vehicle veers an inch away from the road paved with customs and rules, then it crashes into the rubbish heap. Life has fallen. She becomes a fallen woman.

Even now Mariam likes to think from time to time that she and Montu, having locked the house, are going out, carefully stepping on the untidy line of bricks through the water and the mud by the tubewell. Behind them is the empty house, ahead of them the village. At the time, city-dwellers were looking for safe havens, away from meetings, marches, slogans, police firings and the turmoil from the shifts in power play. It was the children who showed the way. The deep shade of the banyan tree, the quiet afternoon lull in the marketplace, the pleasant river bank in the evening, rows of boats with their sails aloft, and the distant fields bathed in moonlight–all these images in the pages of their drawing books echo dimly-lit memories. Many bundled up their belongings and left for those places. But some didn’t. Others returned after a few days, irked by their own childishness.

Mariam forced Montu to return to their village home, but she stayed back, trying to cling desperately to life in a city rocked by turbulence. All her fears were centred around her adolescent younger brother who had picked up an iron rod and wanted to be among those who were creating history in the midst of the choppy waves of protest and repression.

Excerpted with permission from Talaash (The Search) By Shaheen Akhtar, Zubaan. You can buy the book here.

Also read: Are Mothers Machines? A Review Of Interrogating Motherhood

About the author(s)

Feminism In India is an award-winning digital intersectional feminist media organisation to learn, educate and develop a feminist sensibility and unravel the F-word among the youth in India.