Kohima, 2007. A young man has been gunned down in cold blood – the latest casualty in the conflict that has scarred the landscape and brutalised the people of Nagaland. Easterine Kire’s new novel traces the story of one man’s life, from 1937 to the present day. The small incidents of Mose’s childhood, his family, the routines and rituals of traditional village life paint an evocative picture of a peaceful way of life, now long-vanished. The coming of a radio into Mose’s family’s house marks the beginning of the changes that would connect them to the wider world. They learn of partition, independence, a land called America.

Growing up, Mose and his friends become involved in the Naga struggle for Independence, and they are caught in a maelstrom of violence – protest and repression, attacks and reprisals- that ends up ripping communities apart. The herb, bitter wormwood, was traditionally believed to keep bad spirits away. For the Nagas, facing violent struggle all around, it becomes a powerful talisman: “We sure could do with some of that old magic now.” Bitter Wormwood gives a poignant insight into the human cost behind the political headlines from one of India’s most beautiful and misunderstood regions.

Get out of the way, old man!” a hand roughly pushed Mose aside. The owner of the hand then made his way through the gasping crowd. Actually, the terrified crowd had swiftly begun to scatter at his approach, and the killer, holding out his pistol, effortlessly strode out onto the main street. There were no policemen in sight. The killer made his way toward the Dak Lane side-street. Then he began to quicken his pace. All that anyone could hear for a long time was the sound of running feet.

It was over quickly. The young man who was shot lay dead in a spreading pool of blood. Shops quickly downed their shutters. Vegetable-sellers trying to save their goods scampered off with their baskets of vegetables.

After some minutes, there were just a few people left in the crowded market. Mose stayed rooted to the spot, but when everything became quiet, he crept over to look at the body. One of the shots had gone wild. Luckily it was embedded in the wall of a hotel. No one else had been harmed. There had been times when bystanders had been injured, even killed by stray shots in these shootings.

Mose looked down at the body on the ground. The dead man was no longer twitching. Blood-red tomatoes lay crushed under his feet, and vegetables dropped by frightened shoppers were strewn on the ground near him. Sand clung to his mouth from which a small trickle of blood had begun to flow. The blood-spill from his chest was steadily spreading on the ground. He was very young. He looked barely twenty. In death, it was difficult to tell which tribe he belonged to. Short cropped hair, smart clothes and expensive shoes.

Mose noted all these facts quickly, before the police came and unceremoniously dumped the body into a van and rushed it to the morgue. The standard routine was to take the victims of shootings to the emergency unit of the hospital. But it was obvious that there was nothing that could be done for the young man. Once the van had driven off and a police cordon established round the area, Mose turned towards home. He was still clutching the plastic bag in which he had been carrying the chillies and brinjals he had bought just before the shooting.

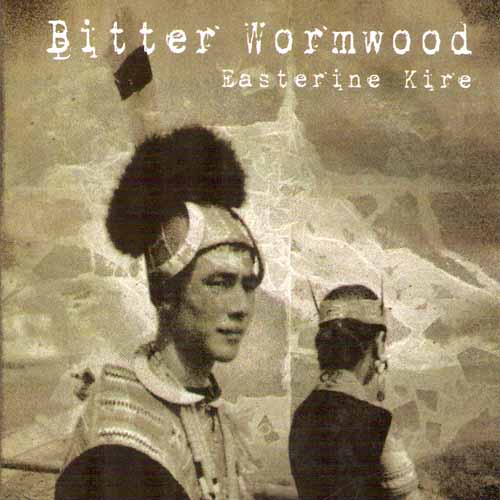

Excerpted with permission from Bitter Wormwood by Easterine Kire, Zubaan. You can buy the book here.

Also read: Aosenla’s Story: Traversing Through Self-Doubt And Power Dynamics

Featured Image Source: Warscapes

About the author(s)

Feminism In India is an award-winning digital intersectional feminist media organisation to learn, educate and develop a feminist sensibility and unravel the F-word among the youth in India.