Chuni Kotal, a Dalit Adivasi woman from the tribal community of Lodha Shabars of West Bengal, was the first woman to graduate from a tribal community. The British, during the colonial rule, defined the Lodhas as a criminal tribe and they continue to live with this stigma attached to them. It was this blemish on the identity of Kotal’s community and the discriminations she faced due to it that led to her suicide in 1992. Thirteen days after her death Mahasweta Devi wrote a commentary on her suicide in the Economic and Political Weekly, and it led to a huge uproar about prevalent casteism in Bengal.

Early Life and Education

Kotal had a poverty-stricken childhood. She starved as a child and worked on fields. Despite having no money to buy books, she continued her education undaunted. She became the first Lodha woman to graduate from high school in 1983.

Afterwards, she worked as a social worker for the Jhargram office of the Integrated Tribal Development Programme. During her time as a social worker for the programme, she undertook extensive surveys of Lothal villages.

After she completed her high school, she started pursuing a graduate degree in Anthropology from Vidyasagar University, and completed her graduation in 1985.

Employment at Rani Shiromani Hostel

Two years after completing her graduation, Kotal was appointed as the superintendent of Rani Shiromani SC and ST’s Girl’s Hostel at Medinapur. She suffered from inhumane working conditions and was discriminated against by the superior officials due to her caste and social background.

She was supposed to work for 24 hours, all 7 days of the week, throughout the year without any leave. Even if she wanted to leave the hostel for a few hours or days, she had to take prior permission from the officials who were insensitive towards her problems.

Once, as accounted by Mahasweta Devi, Kotal’s ailing father came to stay with her for a day or two due to the unavailability of hospital beds. She was accused by an official, from the district office, for ‘entertaining men’ within the hostel premises.

She felt trapped and oppressed in her job. She complained numerous times and went to Calcutta to Writer’s Building. She requested for better working conditions but there was no action from the department, who remained indifferent and unsympathetic towards her plea.

The hostel she worked in was for scheduled caste and scheduled tribe students, and was administered by SC/ST Welfare office, meant for the uplifting the tribals and Dalits. Kotal’s treatment by the officials speaks largely about the stigma attached to and prevalent discriminations faced by the disadvantaged communities.

Enrolment in Masters at Vidyasagar University

In 1987, Kotal returned to Vidyasagar University to pursue her Masters degree in Anthropology. Here, she became a target of harassment and insults by the upper caste professors and administrators of the college. She became a victim of the inner politics between the members of the university. Being a women, she faced two-fold discrimination because of her caste and her gender.

One particular male professor, Falguni Chakravarty, continuously abused and disparaged Kotal from the very first day. He abused her and her caste during the lectures and marked her absent even when she was present in the classes.

Due to this, she was not allowed to sit for the examination on the grounds of ‘irregular attendance’. As a result of this, she lost one year. At the same time she faced a lot of pressure from the district officials for leaving the hostel for studying.

In her second year, the authorities and professors continued to harass her. This time she was allowed to sit for the exams, but was given really low marks by the professor and she failed. Consequently, she lost two years in the University because of the discrimination she faced due to her social background.

Exhausted by all of this, Kotal continuously complained against Falguni Chakravarty, with no response or action from the authorities. Finally in 1991, the education minister ordered for an Enquiry Commission, consisting of three principals from three district colleges, to look into the matter. However, this commission soon got involved in the procedural details with little enquiry of the harassment against Kotal.

All this time, Falguni Chakravarti continued to discriminate against her and referred to her tribe and community as ‘criminals’. He made derogatory remarks about how she doesn’t have any right to be educated because of her ‘low-born’ status and the tribe she belongs to.

During a seminar on August 13, 1992, she was again abused by Chakravarti. By this time she had lost all hope of action against Chakravarti and other administrators by the government or the commission.

She returned to the university, and Mahasweta Devi accounts for her anguish as she talked to a few co-students, “Today in the seminar Falguni babu, quite off the context, referred to the Lodhas as thieves and robbers. In the corridor, he threatened me, I’ll see that you don’t sit for the examination in September. I am a Lodha. So I shouldn’t have dreamt of higher studies. I complained against the offenders, but they remain untouched. Unnecessarily I wasted two years, attended classes but was not allowed to sit for the examination”.

Death

On 14th August 1992, she went to meet her husband, Mamatha Shabar, who worked at a railway workshop in Kharagpur. Shabar, a high school graduate, belonged to the same community as Kotal, and they were in love with each other since 1981. They got married in a court in 1990 but couldn’t stay together because of Kotal’s job. They were supposed to leave for Kotal’s village, Gohaldohi, on 16th August to give a formal reception.

On 16th August, when Shabar returned from his workshop he found Kotal dead. Unable to bear the harassment and heckling at the hands of university officials and teachers, Kotal, at the age of 27, eventually killed herself.

The committee set up by the government following Kotal’s complaints, released its report three days after her death.

Image Source: Chuni Kotal Facebook page

Legacy

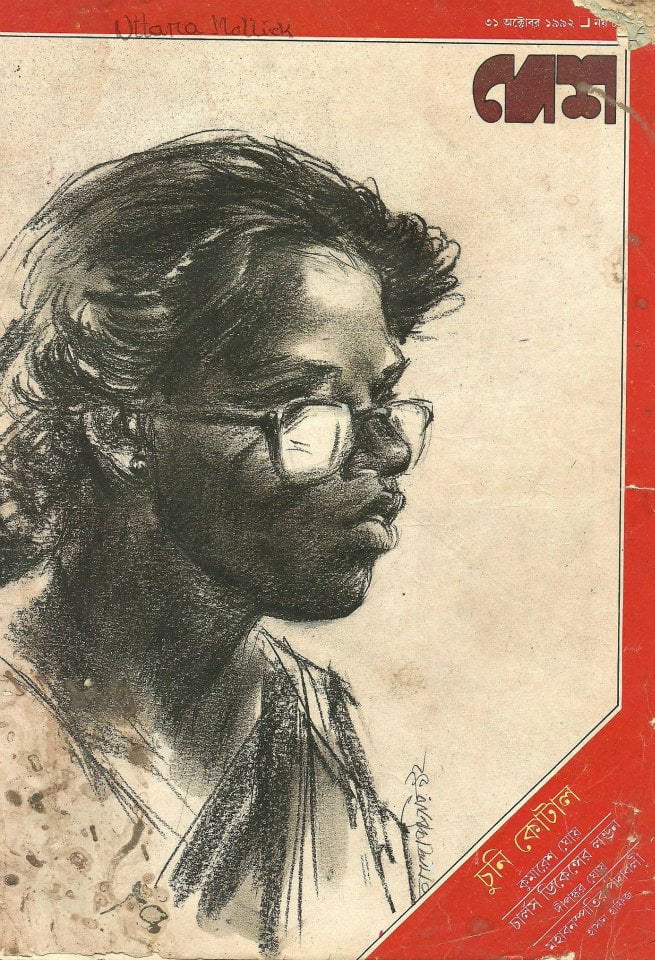

Kotal’s death was an eye-opener for prevalent casteism in university campuses. Her death united the Lodhas and other tribal communities of Bengal against the prevalent casteism in Bengal. Her death became the central point of political and human rights debates which questioned the liberal credentials of the Bengali society.

Her death received a lot of attention from international scholars like Professor Nicolas B Dirks from Columbia University and Professor Jan Breman at the University of Amsterdam. In her book, The Book of Hunters, while describing the functioning of the Bengal caste system, Mahasweta Devi talks about Chuni Kotal.

The Bangla Dalit Sahitya Sanstha spearheaded the movement and organised seminars and street plays, on the streets of Kolkata, to protest against the teachers and officials of the university. Every year, since 1993, the Annual Chuni Kotal Memorial Lecture is organised by them in Kolkata. The Department of Education, Government of India, also produced a motivational video on the life of Chuni Kotal.

The story of Chuni Kotal surfaced again when in 2016, a PhD student of Hyderabad university killed himself. Rohith Vemula, belonging to a Dalit community, committed suicide after being continuously oppressed and harassed for being a ‘low caste’, and it bought in attention the prejudices faced by people belonging to oppressed communities. The suicide of Chuni Kotal and the conditions which led her to take such a drastic step places emphasis on the state and treatment of Dalit Bahujan and Adivasi students.

The unfortunate situation faced by Chuni Kotal is not an unknown phenomenon even today. Casteism is still widely prevalent in many parts of the county, and Dalit Bahujan and Adivasi people still face discrimination in educational institutions, jobs and in society in general.

Chuni Kotal was a brave, inspiring woman whose determination to study and get an education in anthropology is an inspiration even today. Her life and subsequent suicide is reminder of how caste system works in India. As Mahasweta Devi says, “Chuni Kotal’s suicide has ripped the mask off the face of West Bengal under Left Front rule: the caste prejudice and persecution and the government callous indifference.”

References

- Economic and Political Weekly

- The Wire

- Contested Belonging: An Indigenous People’s Struggle for Forest and Identity in Sub-Himalayan Bengal, by B. G. Karlsson, Page 18-19.

- CPI(ML)

- Roundtable India

- The Death of Merit WordPress

- StreeShakti

All images courtesy Chuni Kotal Facebook page

About the author(s)

Prerna is a history undergrad student who spends most of her time reading, dancing and arguing why everyone should be a feminist.