The anonymity of the internet has provided a safe comfort for queer people to explore their identity and form communities. The question is what used to happen before the advent of internet. How did queer women communicate, find comfort, seek relationships, forge solidarities, and confront tensions among their own group and the wider queer community?

This article is not a simple listing of places where queer women used to meet, but a glimpse into what went into these initial efforts to come together, and the fight against the dominant narratives around same-sex love that prevented queer women from talking about their lives, politics and desires.

Arati Rege notes how, at the start of the 1980s, there was almost a complete absence of lesbian women and their lives in movies, discussions and writings. The dearth of sexual awareness and information in conjunction with pressures of compulsory heterosexuality created a situation where “we (queer women) did not even know ourselves.”

The formation and popularity of women’s autonomous groups in the eighties provided the physical space for queer women to meet each other. The possibility of networking granted to them was due to the women’s movement. Many of these groups even forged relations with international organisations – in 1985, Indians attended a workshop for lesbians at the Nairobi Women’s Conference. In the mid-1980’s, many same-sex desiring women met each other through local activist groups.

The dearth of sexual awareness and the pressures of compulsory heterosexuality created a situation where “we (queer women) did not even know ourselves.”

However, the precondition for allowing queer women to enter and stay in these spaces was that they had to be quiet about their identity. They weren’t allowed to assert their love for other women in a brazen, unapologetic manner. Behind this hesitation was the pressure to appease to the mainstream nationalist imagination which saw ‘lesbianism’ as a Western import, trying to infiltrate an essentially Indian culture.

Moreover, these were groups restricted to women involved in activism. Implicit in this was the understanding that the activist circles could not include ‘ordinary’ queer women who didn’t want to engage with the political side of their desire, or be out in public, and instead simply wanted to meet and know others like them.

In an effort of negotiation with ideas of Western imposition of ‘lesbianism’, the term ‘single women’ was adopted instead which provided a community framework for queer women. Hence, from 1987-1993, several women met informally in one another’s homes under the backing of single women’s nights.

The Delhi Group, formed in 1989, was composed of feminist activists who also eschewed the Western label ‘lesbian’ in favour of ‘single women.’

Also Read: I Delete Myself: Anonymity And Sexuality Online

One of the most important efforts to collectivise queer women was taken up by Sappho, established on 20 June 1999, whose initial aim was to provide emotional help and support to queer women and female-to-male trans persons. It eventually grew its activities to fight homophobia and discrimination through a rights-based framework.

LABIA (formerly known as Stree Sangam) was also a queer women collective that was founded in 1995. The initial impetus behind it was the need for women to simply meet each other, as noted by Shahls Mahajan, one of the earliest members of the group. One of their first attempts to come together was at a meeting at Gorai in a rented cottage, which acted as a safe space where women shared their stories with each other. LABIA was and has always been intersectional in their approach, having previously opposed death penalty and ‘ghar wapsi’.

There were even attempts to involve lesbian and bisexual women in initiatives carried out by gay men. Established in 1990, Bombay Dost gave a writing platform to the former. Women across the spectrum, from married women to teenage girls, wrote in, seeking a support system. But after three or four rounds of letters, the move was disbanded due to the lack of an infrastructural system.

Counsel Club, started in 1993 in Kolkata, was meant to be a safe shelter for gay men and women to discuss both overt and covert forms of discrimination faced by them. A regular activity of the group was the Sunday monthly meeting conducted in the apartment of one of the members. The issues discussed in these meetings revealed the anxieties shared by queer women and the ways in which their issues were perceived.

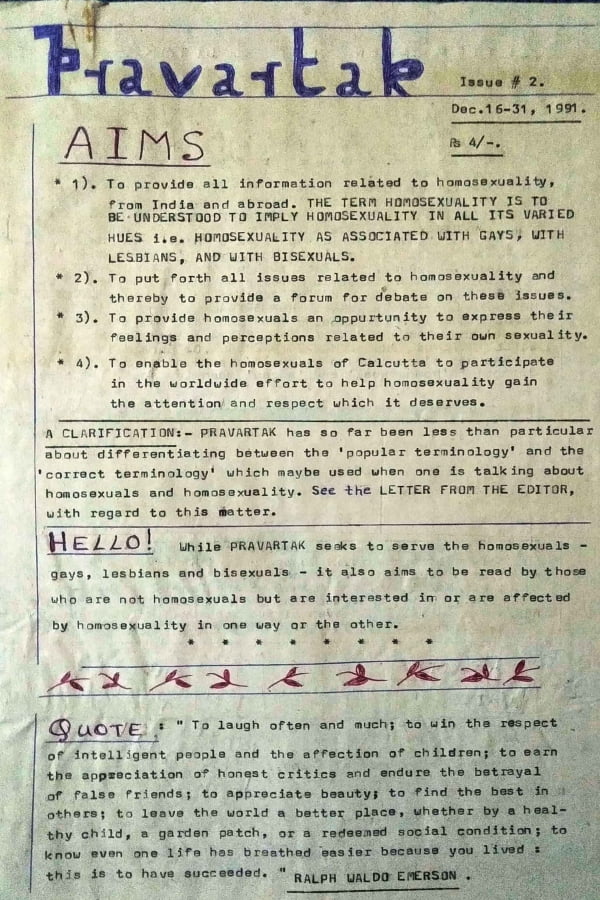

‘Pravartak’-Journal Published by the Counsel Club. Image Source: Varta

The ethics of the question of married women who sought same-sex relationships was debated during these gatherings. It was reasoned that women hardly had any space to exercise agency and say no to marriage and were hence trapped in relationships with men they didn’t choose. Most importantly, the peculiar position that lesbian women occupied, because of the ways in which the intersections of gender and sexuality affected their experiences, was reflected upon. These meetings and involvement of women were seen primarily as an opportunity for men to learn about the problems faced by queer women.

It was only in 1991 that Giti Thadani started the first explicitly lesbian organisation called Sakhi. The organisation created a system of communication for queer women in 1994. All the letters written to them were replied to and once it was ensured that the writer was a woman, a list of postal addresses of women who’d written to them earlier was included and sent to them. Through this, a channel of efficient networking was created by women of Delhi Group from Giti’s flat, was created.

This had a much more profound and meaningful impact than just creating an infrastructure for communication. Indian women from a range of social classes, educational backgrounds, religions found an avenue to not only talk to other queer women but also enter into a world of belonging. Smita, a queer feminist activist notes how,“This kind of a system would have been very very important, simply because these women are not alone anymore. They don’t have to feel like they are the only ones with these desires, or like this is not an Indian thing etc. More importantly, they could keep themselves safe when exploring this alternative side of themselves.”

women who were silenced by hetero-patriarchal norms and shunned by women’s groups found solace in this system of anonymous writing.

Whilst women in urban India had resisted the adoption of the term ‘lesbian’ due to fear of being accused of bringing in decadent Western ideas, many of the women who wrote to Sakhi identified as ‘lesbian’ and even ‘bisexual’. This was mainly because their primary concern was to find a place where they could belong, and hence they accepted titles which granted them an entry into such places and also a sense of self.

A community was hence formed despite the fact that there was no physical interaction amongst members. It was based on the knowledge of each other’s existence and a sense of empathy for each other after the recognition of similar struggles and hopes. A common theme which ran across these letters was the helplessness and frustration over lack of resources and spaces for lesbian women. Anuja, from Ahemdabad in 1991, wrote, “We are very few lesbians [in Allahabad] and also we are not sure of each other, except a few.”

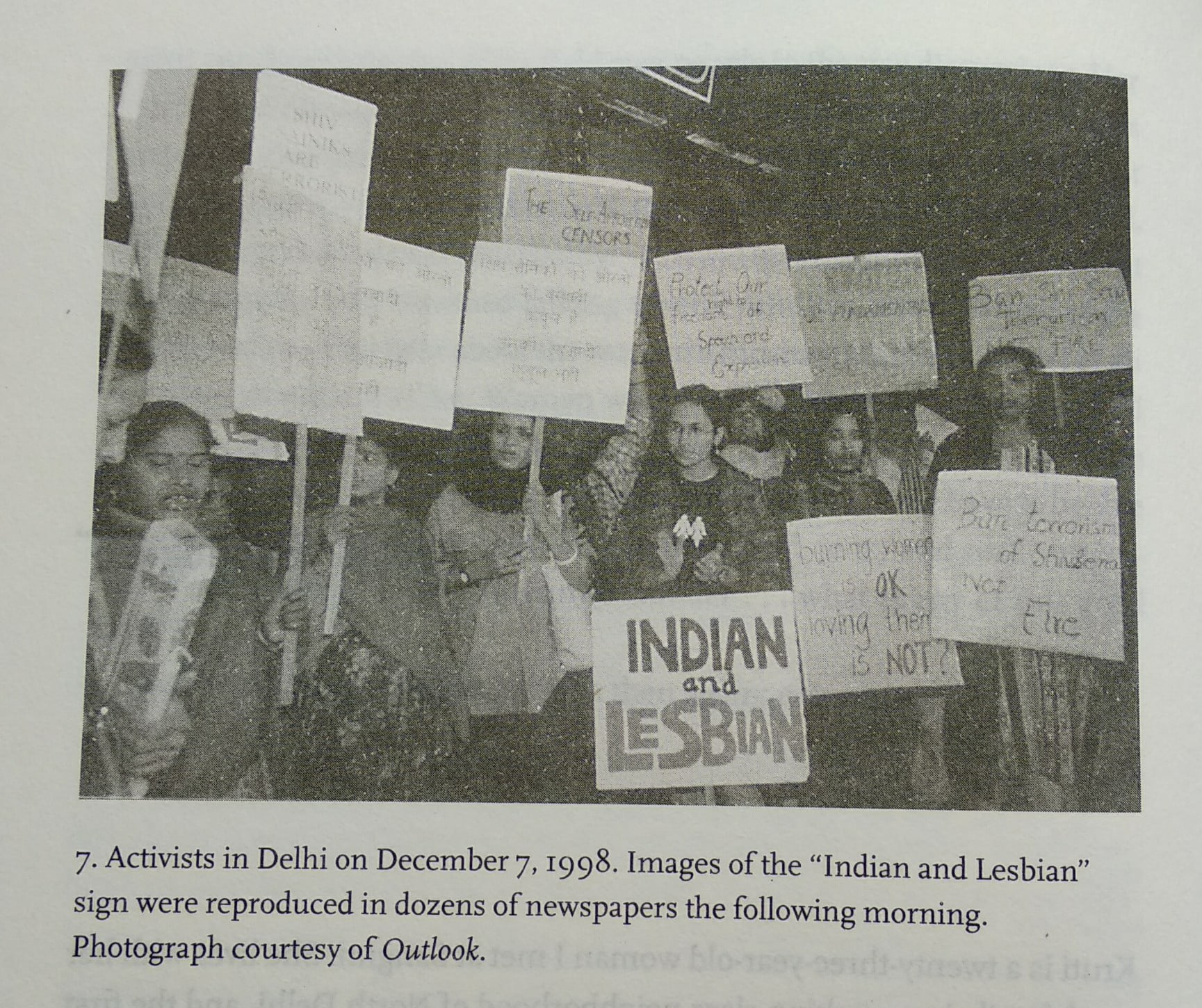

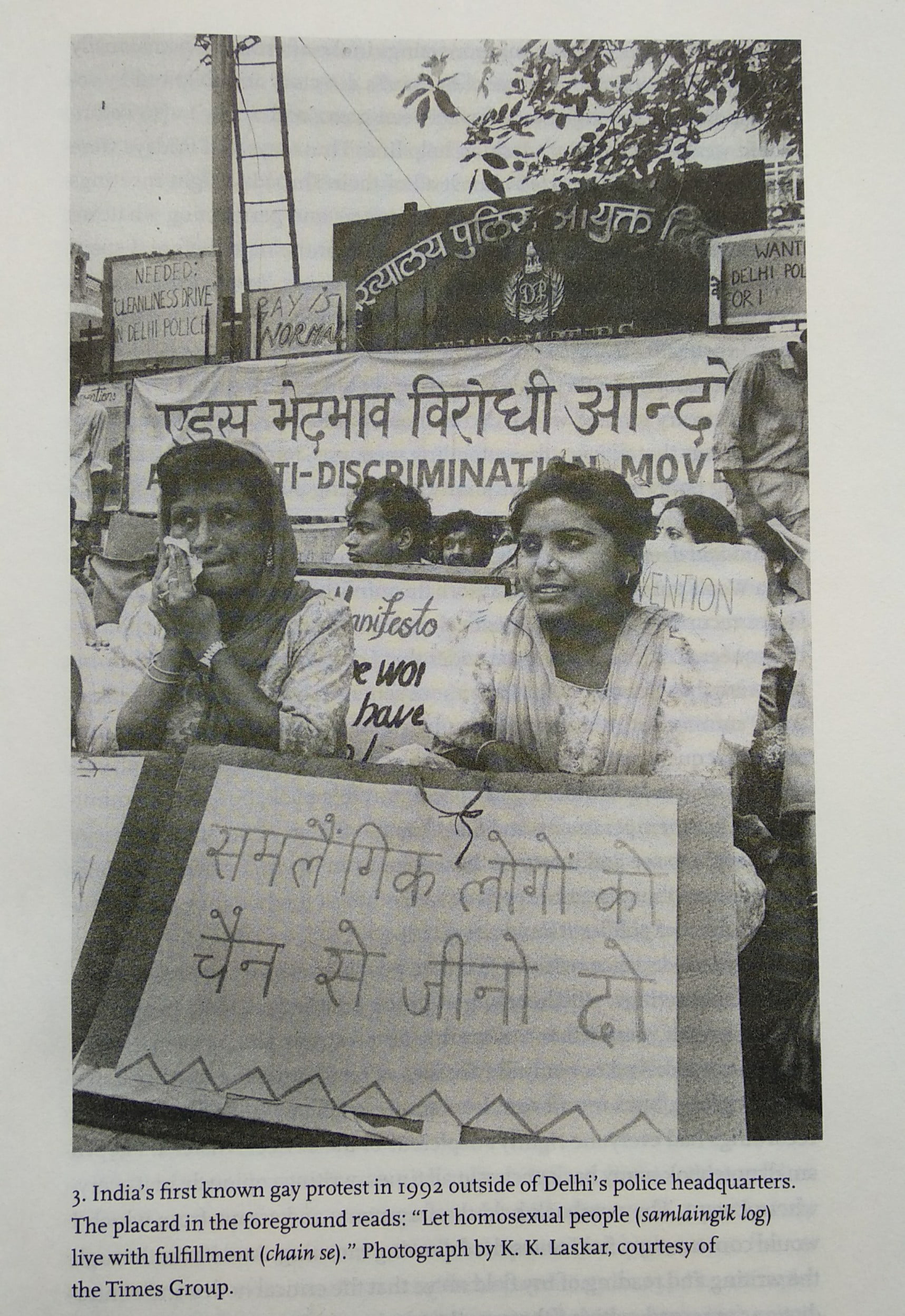

Image Source: Queer Activism in India – a Story in the Anthropology of Ethics by Naisargi Dave

This system marked a change from earlier local activist groups. It was lot more democratic in nature – mainly due to the anonymity afforded to the women. Hence, women who were silenced by hetero-patriarchal norms of their families and communities and shunned by women’s groups found solace in this system of anonymous writing.

Another reason why there was an increase in the number of letters they received was due to the language of self-assurance and respect adopted by Sakhi which resonated with queer women across India. In an interview with Sunday Statesman Review, one of the Sakhi’s volunteers, Aparna said – “My advice to young lesbians is not to crumble under pressure…Believe in yourself.”

The increased communication among these women led to a desire to meet in real life and create a face-to-face community. The community Women to Women, created in Bombay in 1995, was the result of this desire to come together.

Also Read: Let’s Talk About Alternate Safe Spaces For Queer Women In India

However, several tensions and rifts came up with the constitution of such communities. There were two points of contention. Firstly, not all women had the freedom of mobility to participate in meetings regularly. Secondly, many felt alienated since they did not have access to the vocabulary of politics used in the discussions in these spaces.

As a result they came to be dominated by “urban, middle class, upper middle class group of well educated, independent women” who were also at the forefront of local activist groups of earlier times, as noted by Shals Mahajan, a member of Women to Women.

While the activist groupings have sought to fight for rights and visibility, informal networks of communication have served a different but equally important purpose. “A network and community like the one developed by Sakhi, or like the ones created by queers online are more personal, on ground, and community based. Real people are involved, influenced, and affected (positively and negatively) by these networks and communities,” argues Smita.

many felt alienated since they did not have access to the vocabulary of politics used in the discussions in these spaces.

But there is a specific, individual importance attached to both advocacy groups and informal groupings or communities. “I don’t think we can prioritise one over the other. Both kinds of spaces and communities need to exist and be worked upon for overall development,” notes Smita.

The actual importance of documenting the work done by activist circles, of noting the porous boundaries between them being safe spaces to discuss personal issues and political concerns and the creation of alternative systems of communication lies in the need for queer history. History, when written from the perspective of the marginalized, disturbs the stories we so simply accept as important and normal.

References

1. Dave, Naisargi, ‘To Render Real the Imagined: An Ethnographic History of Lesbian Community in India’, Signs Vol. 35, No. 3 (Spring 2010), pp. 595-619

2. Humjinsi: A Resource Book on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Rights in India. Rev. ed. Mumbai: India Centre for Human Rights and Law.

3. Pravartak: Counsel Club Archives. Source: Varta

Featured Image Source: Queer Activism in India – A Story in the Anthropology of Ethics by Naisargi Dave

About the author(s)

Umara is pursuing her bachelors in history from St.Stephen’s college. Feminism to her is an evolving process, she doesn’t feel the need to define her version of it, because she comes from the belief of autonomy of the oppressed classes.