As the hotly contested Transgender Rights Bill gets reintroduced into the Parliament session yet again, what doesn’t seem to change is the reality around that transgender people are trapped in. The Bill introduced so far, struggles to correctly define the various identities of transgender and intersex persons and also fails to address the ongoing violence faced (and legalized) by the community, let alone doing anything to address the deprivation of work and dignity that they face on a daily basis.

Source Image: Huffington Post

Courtesy the human rights activism across the world, we now have conversations around transfeminism. But decades back, to exist as a trans person and establish an identity was not for the faint-hearted. It took a gritty and fiery Mona Ahmed to be declared an outlander, establish herself and extend love to others while she remained the muse of artists.

Also Read: Responses From Trans & Intersex Communities On The Transgender Rights Bill 2016

Early Life

Born in Old Delhi in 1937, Mona was assigned male at birth. This was after two daughters in the family. Mona’s father, a maker of traditional skullcaps, was thrilled about it and named the child Ahmed. Because yes, the birth of a boy has always been the ultimate reward in patriarchy (sigh!). However, as the truth about her being a transgender woman dawned on everybody, Mona’s life took a dark turn. From harassment and abuse that she faced from teachers and boys at school, to her being the object of her father’s fury while he attempted to strangle her in sleep, it was all a part of growing up.

Mona succumbed to depression, took to alcohol, and finally, complained to the police about the assault she faced by her father, and by the community at large that abused her on the account of being ‘unfit’ to belong. Going to the police was considered to be the ultimate act of betrayal and she was beaten up by her own loved and known ones and ostracised.

Eventually, as she grew out of her young adult stage, she left her “blood family” and flew from home with a group of transgender people to transition in a town outside Mumbai and thereon, named herself ‘Mona’. This process was exceptionally tough to be carried out in secrecy owing to the stigma as well as the attached cost. In recent times, courtesy ongoing activism, there is an increasing demand for free access to gender affirming medical procedures. A win-win is the case of Kerala, that has taken the lead to publicly fund such surgeries. Yes, we have taken some baby steps, but there is a long road ahead.

From harassment and abuse at school, to her being the object of her father’s wrath while he attempted to strangle her in sleep, it was all a part of growing up.

The Making of a Muse

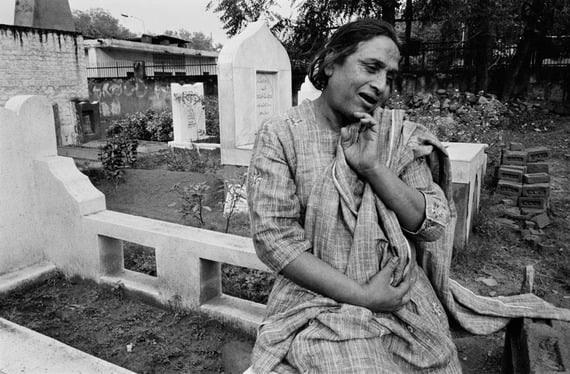

Mona carved a new life for herself in a place where no living person ‘fits in’ – a graveyard. She staked out a plot in Mehndiyan, a graveyard in Delhi, claiming that a handful of aged headstones whose names had been washed clean over time belonged to her ancestors. From a square barely big enough to sleep on, she built a house that included rooms for her nephew and her caretaker, Jahanara. In times to come, the place served as a home to sex workers, beggars and many others, for over three decades.

Source Image: The Hindu

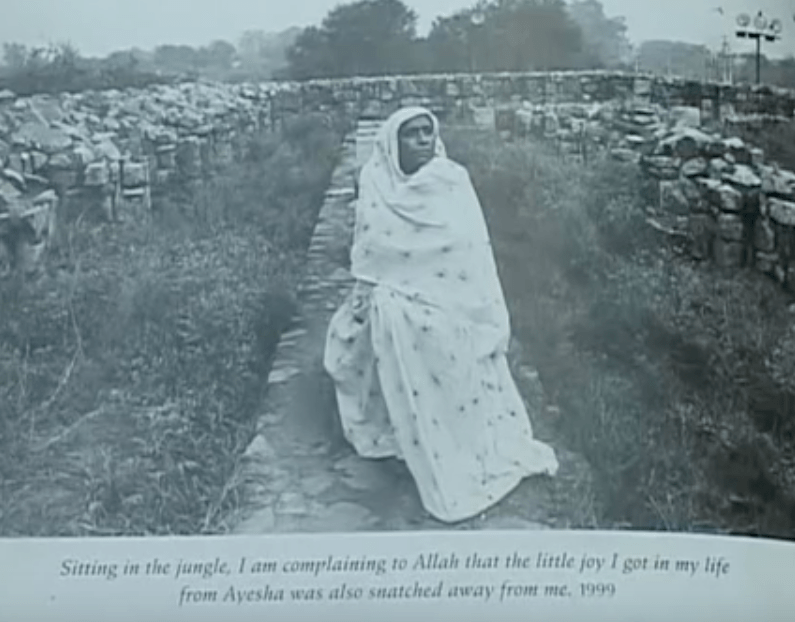

In her middle years, Mona started to long parenthood and the desire was intense enough for her to trip to Haj to pray for a child. Her wish was miraculously granted. A woman she knew died during childbirth, leaving her infant daughter. Mona took her in, named her Ayesha, and turned her into the centre of her existence. Mona would organise lavish birthday parties for her little Ayesha. Trans folks from across the subcontinent would come in to partake of the revelries. The singing, dancing, and feasting would go on for days. Hundreds of them, from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India would gather. In a way, the national meetings of the trans community used to be at Ayesha’s birthday parties.

Mona’s life with Ayesha did not last long. In a few years’ time, Mona’s guru Chaman, who was very close to Mona earlier, grew uneasy about Mona’s love for Ayesha. She abducted Ayesha and took her away to Pakistan. And here was yet another period for Mona that broke her down. Within the hijra world, even today, gurus fulfill the hybrid role of den mother, godfather, spiritual leader and pimp. No chela (disciple) dares to go against them.

Source Image: Youtube

However, she relentlessly went on. Her long-term companions were not the middle and upper classes, the ‘normal’ people whose normalcy is usually aspired. Rather they were the down-and-outers, the ones who themselves inhabited the margins: the battery boys who manned large commercial batteries, the girl who was pushed off a train by men trying to assault her and lost a leg when she fell out, the naan-khatai maker who sought shelter in her home, the gravedigger who worked to earn an income for his son, the bent-over woman who went out in search of food (and occasionally husbands) every day.

According to Dayanita Singh, a journalist who eventually grew to be a thick friend, Mona displayed an extraordinary exuberance and was ‘never short of ideas’. She had the zest to do more and more.

“I have tried to start shelters for vagrant women and children,” said Mona, “There is a room for rent in the adjoining lane. I am thinking of using it as a home for women who have nowhere to go. Maybe I could also start a clinic to treat HIV positive people of my community. A while ago, I had 50 beds built for children. But people broke them and sold off the wood. I had also made a swimming pool for girls and a hall where poor people could get married and host a reception. None of the two structures were used for the purposes they were built for.”

Dayanita mentioned that she could not convince Mona that women would not come in for a swim in a graveyard and that people would not consider it to be the best venue to get married in. “When Mona puts her mind to something, she makes sure she does it.”

In a way, the national meetings of the trans community used to be at Ayesha’s (mona’s dAUGHTER’S) birthday parties.

Perched on her bed facing a giant flat-screen television hung on the wall, Mona built and ran an empire, which once consisted of a menagerie of animals – a dog, a monkey, a rabbit, a family of ducks, and goats – all of which had been stolen, killed or eaten up by other animals or her neighbours over the years. The only constant in her life had been the steady stream of people who keep flowing in and out of her house – friends, family, fellow hijras, hangers-on, local children, destitute women – anyone who needed a place to crash.

Mona was somebody who welcomed strangers and aspiring/confused transgender people. “Her door was never locked. You could just push it open and walk in, and she might be sleeping on her bed but you could still go in and watch television while she slept, it made no difference to her,” marked Urvashi Butalia, a close friend of Mona and a renowned publisher.

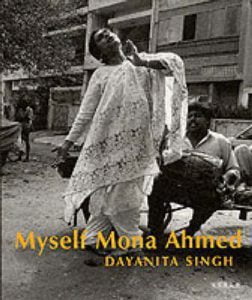

Years ago, when Dayanita Singh had asked Mona if she would like to tell the story of her “unique self” in a book, Mona had been thrilled. “The world calls me a eunuch, but you call me unique,” she had said. Thereafter, she had got a board painted with the words ‘All India Unique Welfare Association’ and hung it over her door.

Source Image: Book Depository

Mona did not just rise to be an apostle of gurus who ran Delhi’s ‘trans underworld’ but also a muse for Dayanita Singh, who published snippets from Mona’s life as photographs. Myself Mona Ahmed, a ground-breaking book, was published by Walter Keller on behalf of a pioneer publishing house, Scalo. The book was a collection of profoundly honest and frank emails sent by Mona Ahmed to Walter Keller about her life, and reflections on her own identity and struggles.

Reflections on the Gender-Bender

In a letter to Walter, Mona once wrote:

“I constantly think, “Why did God make eunuchs?” A mother has 4 children, why is just one a eunuch? Of course, it is from God, but why does only one boy feel he wants to dress like a woman? What this is, I do not understand. No one can explain this question…”

She was a reflective person who often got into debates (with herself and others) on what a non-conforming identity meant and where it was manifested.

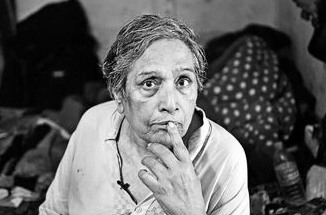

Source Image: Live Mint

Mona, however sceptical about her own identity, was clear that she did not want to mainstream herself. Once, on being asked by Dayanita Singh whether she would like to consider going to Singapore for transitioning, she said, “You really do not understand. I am the third sex, not a man trying to be a woman. It is your society’s problem that you only recognise two sexes.”

Urvashi Butalia, when asked about Mona, spoke about the issue of identities being linked to the body. “Is gender identity premised on the body? So that a sex reassignment surgery or an excess of certain hormones can be taken to define who you are? Perhaps she (Mona) knew something about identity and its ambivalences that those of us who are trapped in so-called ‘normal’ identities don’t.” Mona’s thoughts are echoed by trans activists today whose protests to Transgender Bill (2016) maintain that the way transgender is defined – the purview of male-female (half, combination, neither!) – is problematic and needs to be addressed.

I am the third sex, not a man trying to be a woman. It is your society’s problem that you only recognise two sexes.

The documentary Main Mona Ahmed (I Am Mona Ahmed) features several transgender people speaking about their aspirations. One of them says, “I want to marry, like ‘normal’ people”. Mona had a radical opinion about marriages amongst the queer. “Even if the law might allow hijras to get married and have a family, who will marry us?” she says. “Two men or two women can marry each other, have children, and be a family. But not us.”

The other huge impediment in the capitalist world that Mona saw was about how work and the trans population were linked (or de-linked?). “The other problem is, if you are making thousands, sometimes lakhs, simply from badhai (money collected by eunuchs from families for blessing newborns), you won’t want to do any other work, will you? For years, our community has lived off earnings made by dancing at weddings,” she said. “Now they beg at traffic-lights and on trains. It will be hard to do a nine-to-five duty. And (then, the biggest question is) who is going to give us a job anyway?”. While the latter question still surrounds the population, they are now double-trapped under begging prohibition laws and are often harassed and booked even when they are merely present at public places.

Who is going to give us a job anyway?

Today’s reality for the transgender population isn’t limited to discrimination or stigma, but extreme forms of hate crimes that are prevalent against anyone who does not conform to the gender binaries of man-woman. Every now and then, media is outstripping stories that illustrate the ostracisation and harassment faced by the transgender community in India. Increasingly, their population is forced to participate in sex work and the rate of HIV among hijras is more than 100 times the national average which is further leading to violence against them of all sorts, making for a vicious cycle. To add to the atrocities, the Transgender Bill (supposedly created in contemporary times) dealt with the issue of violence in an amateur manner, disregarding the vulnerability of this population.

Also Read: Queer Marriage: Should We Call It Subversion Or Submission?

An End to an Odyssey

Source Image: Live Mint

Delhi’s most iconic transgender individual, Mona Ahmed passed away at the age of 81 on September 9 2017 due to ill health. Her tireless spirit was such that even on her deathbed, the widely photographed Mona was on a video call to Venice.

She was buried in the same graveyard in Mehndiyan, where she had established her empire. Her home still is dipped in pride as the journey of her life rests in photographs all over the walls of her home – the pride that emanates from not vying to be mainstream, rising up every time the society and closed ones stabbed her identity and keeping herself upbeat against all odds.

Featured Image Credit: Thomson Reuters Foundation

i would be glad if the writer did not use ‘gender-bender’ in this article. Gender and sexualities are spectrums, and mona ahmed did not bend her gender , as she saw herself as a transgender woman. Gender-Bender is an offensive word.