Manto is set in a very different time from ours. It is the story of a man living in British India, who lives through the Partition. His story occurs in a vastly divergent socio-political and economic climate, but a story set in a different era, a different world, still resonates with all of us today.

Saadat Hasan Manto may no longer be, and our understanding of obscenity and morality might have changed to take a slightly different shape. Our collective ideas of freedom, expression, literature, and sexuality may slightly vary from those of his time. Still, the practice of meting out punishment to those who hold up a mirror to our violence, cruelty, and hate, to anyone who decides to say what we don’t wish to hear or believe, to everyone who attempts to shatter our delusions about what we are and what we are becoming, still exists.

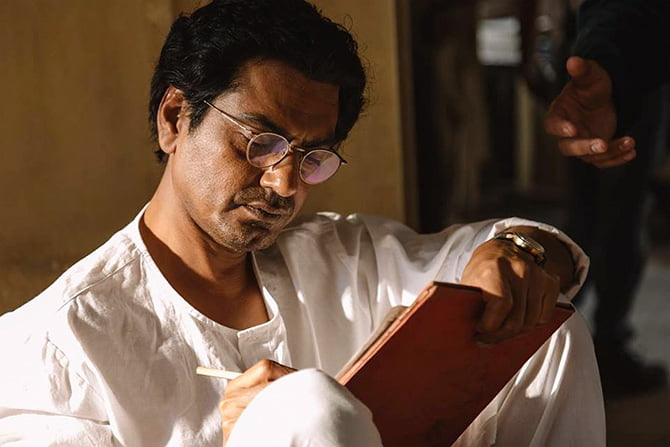

Manto by Nandita Das, starring Nawazuddin Siddiqui in the titular role is the story of the acclaimed and controversial Urdu author, Saadat Hasan Manto and five of his most celebrated and acclaimed stories seamlessly woven into the gripping plot of his life and a criminal trial for obscenity.

Manto’s stories that held a mirror to everything he deemed wrong in his society were bold, fierce, angry, and honest, but also rather unheard of and scandalous.

In the India of the 1940s, Manto’s stories that attempted to hold a mirror to everything he deemed wrong or outrageous in his society were bold, fierce, angry, and honest, but also rather unheard of and scandalous. Manto and his contemporaries like, Ismat Chughtai, faced multiple charges for ‘obscenity’ in their work, usually involving women and either their plight in a patriarchal society that doesn’t value them or their desires in a world where they are penalised for having them.

Saadat Hasan Manto was a celebrated author and scriptwriter based in Bombay. Manto who was an atheist and gave almost little to no thought to his religious identity as a Muslim man – by virtue of being born in a Kashmiri Muslim family – but following the Partition and the communal violence it birthed, he was forced to confront this identity of his, which had begun to define his entire being and posed a great risk to him and his family. With his friends turning on him and his identity as a Muslim man superseding everything else he was, he made the abrupt and painful decision of migrating to Pakistan, a decision which marked the beginning of his unavoidable decline.

Also read: Manto’s Mirror To Partition: A Feminist Review Of ‘Khol Do’

Moving away from Bombay, leaving behind everything he knew and loved had a profound impact on him and watching refugees struggling to survive in the now crime-filled streets of Lahore only further worsened his distress and filled him with agony and foreboding.

Manto’s work was inspired by what he saw around him, and as the communal and sexual violence caused by the Partition worsened, his stories took a dark turn, but they accurately and honestly explored the impact of the Partition on everyone, especially on women.

Manto’s highly controversial and acclaimed, Thanda Ghost was inspired by the sexual violence he saw around him. This story would be what would ultimately put him on trial for obscenity, but it continues to be a harrowing and honest reminder of the plight of women during the partition. The story is of a man who is unable to have sex with his wife, Kulwant, who suspects he is having an affair and stabs him with his dagger. As he is dying, he narrates to her the real reason he is unwilling to sleep with her. He recalls his previous attack along with a few other rioters on a village, in an attempt to either drive away or kill the Muslim residents. In one of the huts he found a girl who he took to the outside of the village with the intention of raping her, and as he set her down to rape her, he realised she was already dead.

as the communal and sexual violence caused by the partition worsened, his stories accurately explored the impact of it on everyone, especially women.

This seemingly has a large impact on the man, and he seems to be agonising over it in his dying moments. The story uses explicit language, and portrays Kulwant as a sexual woman who takes charge of her sexuality, and the story also delves into the subject of rape and abuse, themes that were considered taboo in Manto’s time, but this kind of a story involving the realities of sexual abuse was not shocking given Manto’s body of work. A lot of his stories follow similar themes, like Khol Do.

The film explores the disdain and shock of the characters upon reading his work, and Manto’s struggle to write about the barbarity that he saw, without being penalised for writing the realities of his era. While he is shown to have allies like Ismat Chughtai back home, who faces similar struggles and friends who stand by him, in Pakistan where he has no literary circle, he is pushed into isolation.

The movie also portrays him as a feminist and Manto, though he never would have called himself that, was a feminist in his own right. Manto wrote extensively about women, not with a voice of condescension or superiority, neither was he attempting to appropriate their stories and struggles. He spoke as an ally, who was opposed to how they were treated, dehumanised, commodified, and disposed off during the Partition.

His characters, like those of Kulwant from Thanda Ghost, are often headstrong women who also are unabashedly sexual beings. In Khol Do, a father is glad his daughter is alive and doesn’t seem to wish death upon her because she was raped, to protect their honour. Manto’s feminist voice in a time when women were treated as the spoils of war and discarded once they were abused, was of paramount importance.

The escalation in communal violence that the Partition brought about also saw an escalation in sexual violence against women, where abusing women became synonyms with dismantling the honour of the community a woman belongs to. With his writings Manto sought to shed light on this and vehemently oppose it.

In spite of all this, the movie perfectly encapsulates his struggles and decline, while not putting him on a pedestal and liberally highlighting his flaws. True to history, he is portrayed as an alcoholic, who made the impulsive decision to flee his country that ultimately led to his life spiralling out of control and to his early death.

It doesn’t portray him as a perfect man who rises to the occasion and adapts to changing times the best he can, for his own sake and for the sake of those he loves. Instead, it looks at his decline, and the pain, resentment, and fear he lived with which ultimately caused him to perish.

Men in Bollywood are often portrayed as exceedingly courageous, unbreakable, and above pain and fear, but Manto is portrayed as a man who is scared, who is angry and carries resentment for being torn away from everything he had known and loved. The violence and dearth of humanity around him fills him with an impending sense of uncertainty, with which comes deep fear.

the movie perfectly encapsulates his struggles and decline, while not putting him on a pedestal and liberally highlighting his flaws.

Siddiqui’s character by no measure lives up to the ideas of the ‘real man’ in Hindi cinema, who depends his entire worth on internalising toxic masculine ideas and on acting upon them. Manto is scared and vulnerable, but this portrayal is what makes his pain and agony seem real. Manto is revolutionary in the way Siddiqui’s character is portrayed, for the male protagonist in a Hindi movie to be anything but the toxic idea of a ‘real man’ is almost unseen and unheard of. He isn’t an impenetrable man who cannot be broken, his world changing around him profoundly impacts him and even breaks him, and this is what makes his pain and anguish seem real.

During the end of his trial, he proclaims, “My story is literature and literature can never be obscene” and he claims he wrote as he saw and there is nothing he can do if the naked truth is ugly, and these words are still true today.

Our times aren’t too different from Manto’s times, in our society that perpetuates rape culture and where rape apologism is prevalent, we still cannot bear to see our truth. Manto was charged with obscenity for Thanda Ghost because it dealt with rape and the barbarism of the partition. His well-known story, Khol Do was also condemned for the same reason, and nearly seven decades on, we continue to condemn and silence any voice that forces us to confront our patriarchal attitudes and our epidemic numbers of sexual harassment and violence.

We continue to declare these staggering numbers as slander and our collective attitudes towards women fuelled by toxicity as vicious lies. We label anyone who writes, speaks, or in any other form attempts to get us to see this as anti-nationals or as people who hate their identities as people of colour, so are attempting to put this country down to emulate the West.

Also read: Saadat Hasan Manto And His ‘Scandalous’ Women

This begs the question, how different is Manto from today’s Shujaat Bhukari, Gauri Lankesh, Salman Rushdie, or any other voice of dissent that exists in any shape or form? Ultimately, how divergent is today’s India from that of nearly a century ago? With this we are coerced to confront the question, how far have we come as a society and has it been adequate?

Featured Image Source: Variety

About the author(s)