“There is nothing connected with the staging of a motion picture that a woman cannot do as easily as a man, and there is no reason why she cannot completely master every technicality of the art,” – Alice Guy Blache

My relationship with cinema strengthened when I traced back to the work done in the field of cinema between the 1890s and 1920s, and discovered Blache’s The Consequences of Feminism, a piece of narrative fiction that made us imagine a society where the roles of men and women are inverted and slightly ‘effeminate’ men sew, iron, and take care of the children, while ‘macho’ women drink and read newspapers in cafés, and court men.

Then came Lois Weber, the mother of intriguing silent cinema who made provocative movies like Hypocrites, which featured full frontal nudity and Where are my Children?, which was about abortion and birth control, followed by German director Lotte Reiniger, the pioneer of silhouette animation, making the use of fluidity in her films in her style of expressionism, Germaine Dulac, who steered the art of filmmaking into the unchartered territories of surrealism and impressionism, Mary Ellen Brute’s abstract musical films, Maya Deren’s experimental cinema, Chantal Akerman, Vera Chytilova, Doroth Arzner, Leni Reifanstahl, Ida Lupino and many others.

Also read: 7 Badass South Asian Artists You Should Know About

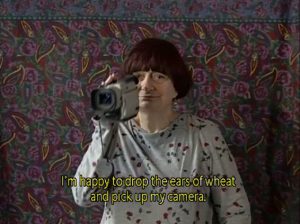

I remember watching The Gleaners and I by Agnes Varda where she demonstrates the work of gleaning that women used to do in crop-fields before the era of agricultural machinery evolved, poses in front of Jean Francois Millet’s painting of the same name with crops on her shoulders, and later drops them and places a camera on her shoulder gesturing about the eventual progress of women from manual field work to the reserved spaces of art.

Image Source: Esquire Theatre

Women in art intrigued me because they were the living examples of how far we have come as a society, from the times when women were not allowed in classrooms and could not dream of escaping from household chores to a room of their own to think, write, create, to this day when they are barging into villages or city spaces with a camera feeling the pulse of the world and reflecting its reality in a visually appealing form. Documentaries are whistle-blowers for a country where nothing can be openly talked about. They are resistances which do not need arms or ammunition.

Women in art intrigued me because they were the living examples of how far we have come as a society.

They challenge the normalised and internalised forms of oppression (especially the oppression of thought and dissent) and make us question our own hypocrisies using clever methods such that the discomfort of change comes in a way which isn’t abrupt or offensive, but so poetic and personal, that we take the question back home with us, re-run it in our consciences throughout several sleepless nights and one day, wake up to the more tolerant and emancipated versions of ourselves.

Women reigning fields like these vests upon them the power to take feminism a step further, by introducing intersectionality in it, as they cover the struggles of particular groups of adivasi people or the outskirts of an invisible town where dwell the ostracised transgender individuals struggling to build a respectable identity, or other women, who are the worn-out housewives, the vilified sex workers, the ‘inauspicious’ manual scavengers and the forced upholders of honour.

Image Source: Bay Swan

I explored some of the work done by female documentary filmmakers in India to make a better sense of the art and the activism and discover works beyond the popular examples like Deepa Dhanraj’s Something like a War (on India’s family planning program), Nishitha Jain’s Lakshmi and Me, and Shohini Ghosh’s Tales of the Night Fairies (reflects upon contemporary debates around sex work by covering people involved in the industry)

1. The Other Song by Saba Dewan

Image Source: Institute Of Contemporary Art

The Other Song strenuously ventures into the haunting expanses of Hindustani classical music in Benares, Lucknow, and Muzzafarpur and explores courtesan cultures lost in history – the last of ‘Tawaifs’, interspersed with kothis and musical instruments, galis and temples, that dot the landscape. A delicate narrative device is used to weave it all together which is a song by Rasoolan Bai, Lagat jobanwa ma chot, phool gendwa na maar (My breasts are wounded; don’t throw flowers at me) recorded in 1935 gramophone recording. As she traces back to the origins of the song, she meets its various altered forms in the way and proves very subtly, how history loses its originality and factuality over long periods of time.

2. Kabir Project by Shabnam Virmani

Image Source: Scroll

I stumbled upon the Kabir Project while reading Tagore’s translations of his poetry. Virmani takes us on a journey throughout India to find the real Kabir, only to realise that Kabir too was claimed by various cultures and different religions like disputed lands or shared national boundaries often are. This film journeys through song and poem into the politics of religion, and finds a myriad answers on both sides of the hostile border between India and Pakistan to the question, “Who is Kabir’s Ram?”

3. Mod by Pushpa Rawat

Image Source: The Hindu Businessline

Like Pushpa Rawat’s Nirnay, in which she had already asked uncomfortable questions about choice, personal freedom, happiness, and compromise, Mod takes documentary filmmaking to another level by making the camera a character in the lives of others. While attempting to reverse the male gaze, Pushpa becomes a part of her subjects and understands them by getting into their headspaces. She decodes the complicated, repressed minds of young men who are the perpetrators and participants of patriarchy by observing them like a fly on the wall at their main joints of socialisation, where they have personal conversations about their priorities and worldview.

4. The World Before Her by Nisha Pahuja

Image Source: The Hindu

This film explores the contrasting identities of Indian women by profiling two young women participating in very different types of training camp – Ruhi Singh , who aspires to become Miss India, and Prachi Trivedi, a Hindu nationalist with the Durga Vahini. Ruhi Singh believes that modernity is not synonymous with westernisation and it’s possible for women to be rooted in their native culture and also be free. Her version of freedom and ambition is competition in terms of beauty, such that even commodification does not matter to her because she feels herself lucky to have survived in a world where girl children are killed either in the womb.

They challenge the normalised and internalised forms of oppression and make us question our own hypocrisies.

Prachi comes from a different class. She refuses to believe that a woman is complete only after motherhood or marriage should be the end goal of her life. At Durga Vahini, she has found a purpose to cling to in the otherwise meaningless labour of living where her fate is decided as a daughter who was always her parents’ obligation and her prospective in-laws’ slave. While on one side, behind the glass doors of the expensive parts of Mumbai, women go through Botox sessions in order to ‘polish’ their grace, femininity, and sensuality, in the camps of Aurangabad, Prachi learns to use a sword and a rifle because for her, equality for women would mean them walking in the paths of masculinity – precisely, the paths of violence.

5. Films on Art, Culture, Music and Art-Activism

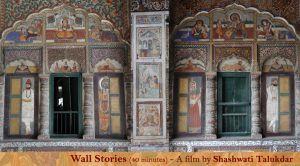

Image Source: India Foundation For The Arts

Women filmmakers have also worked on documentaries on art, music and dance which are yet to find popularity with the audience. Breathed Upon Paper by Ayswarya Sankaranarayan, Rasikan Re by Pooja Kaul and Wall Stories by Shashwati Talukar introduce us to 18th century pahari miniatures, Moghul miniature paintings and art work done in the Garhwal region in engaging and innovative styles.

Sonya Fatah’s I, Dance tells the difficult story of classical dance in Pakistan while set against the largely military backdrop of the country while Gali by Samreen Farooqui puts light on the subculture of B-boying and breaking as an Indian form of contemporary street dance.

Kho Ki Pa Lu co-directed by Anushka Meenakshi and Iswar Srikumar is an interesting musical portrait of a community of rice farmers in the village of Phek in Nagaland, where they take the help of songs to struggle through their exerting daily labour and to make their personal stories heard.

6. Films on Labour

Image Source: Youtube

Down the Rabbit Hole and A Very Old Man with Winged Sandals by Ekta Mittal and Yashwini Raghunandan are precious films made on the labour force of India. But Divya Bharathi’s Kakkoos is unmatchable. It is a Tamil documentary made on the Dalit manual scavengers of the state, educating us about what the definition of a ‘manual scavenger’ is, its legal position and its intricate relationship with caste, the absence of regularity in wages and safety gear provisions for the community, and importantly, the unfortunate cases of ‘sewer killings’ which reveals how the Dalits’ lives do not matter to a government who sells off the guilt of these ‘orchestrated murders’ with meagre compensatory amount offerings.

7. Some Stories around Witches by Lipika Singh Darai

Image Source: Incredible Orissa

Lipika Singh Darai takes us to the tribal villages of Odisha in her documentary Some Stories Around Witches on the politics of witch hunting, the myths and superstitions attached to witchcraft and the humanitarian crisis surrounding it.

On having the opportunity to meet and talk to her at the Indian Film Festival of Bhubaneswar, I asked her about the challenges that a female filmmaker has to face in the remote areas she travels to, for recording ground realities like the electric pole lynchings of alleged ‘witches’ shown in her film. With a welcoming smile, she says, “I had a dependable crew who helped me out in travelling and shooting, and had acquaintances from the villages itself who made the conversations easier to take place. But had I been an one-woman-army like the Assamese film director Rima Das, I am not sure how I would have pulled it off “.

Also read: Divya Bharathi’s ‘Kakkoos’ And The Casteist Reality Of Manual Scavenging

She said and left, while I walked back slowly to the festival screen to watch the next scheduled film, Village Rockstars by Rima Das herself. And as I was fascinated by the fact that the director of the beautiful film was also its screenwriter, executive producer, editor, production designer, and cinematographer, little did I know that months later it would be India’s entry to the Academy Awards. A woman’s movement had started in the cinema scene of India long ago, but at this point of time, its roaring, raging, reclaiming the art spaces which always belonged to us but had to be fought for nevertheless.

Featured Image Source: Bay Swan

About the author(s)

Bijaya Biswal is a 23 year old doctor who works for the upliftment of the culture of literature, films and art in Odisha. She has been also working with LGBTQIA+ rights, animal welfare, ecology and menstrual health.