When I was sixteen a male tutor of mine thought it was okay to comment on my outfits every day. He talked about how my clothes hugged my body or how he liked certain colours on me rather than others. That’s how it started but then it eventually turned into him feeling confident enough to sit extremely close to me. Every class he would happen to drop a book and pick it up with the support of my legs or thigh.

On our final day of class he asked me to come to the centre around 7 pm. I went and found the centre completely empty, it was dark and there were candles lit everywhere. He had this weird grin on his face, and kept asking me how the centre looked. Despite the fact that the entire centre was empty he asked me to come into a room and start class there. A knot formed in my stomach and I told him I forgot something in the car, I left the centre and just never went back. I never mentioned this to anyone. Partly because I was embarrassed and partly because a part of me kept telling myself that it wasn’t a big deal. Nothing had happened to me. I was ‘safe’ but there was this pit in my stomach every time I thought of him or that centre. It made me feel dirty.

Also read: #MeTooIndia: How Toxic Masculinity And Misogyny Caused Me Trauma

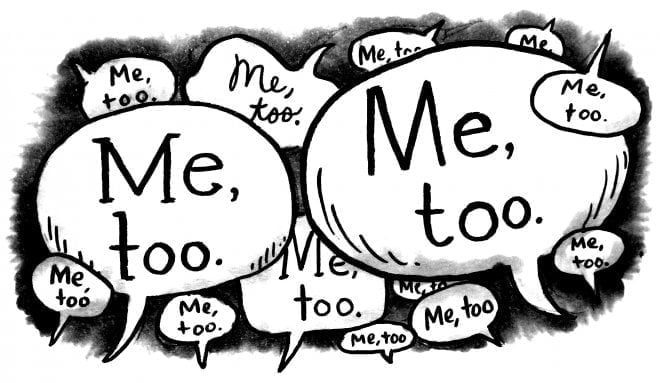

So I say #MeToo, just like numerous other women who came out and shared their experiences of sexual violation through this movement. For me, the #MeToo movement did something radical but I never really understood exactly what until I had the privilege of meeting Tarana Burke, the founder of the movement. Tarana Burke in her talk at my university, argued that strides in the fight against sexual assault can not be measured through gaining of power, but the dismantling of an intricate culture that puts women, specifically women who lie in the margins of society, as subordinate objects that can be physically and violently exploited. She applies a form of black feminist epistemology that gives objectivity to lived experiences, to make strides in this movement.

Burke began her speech by talking about her own personal experience as an activist who is also a survivor of sexual assault. She allowed her own lived experience to be part of her epistemology that shapes her experience. Black feminist epistemology lays emphasis on one’s ‘standpoint’ allowing voices of individuals lying on the intersections of society to be highlighted.

Burke does exactly this by giving credibility to lived experiences – not to say the activism focused on dismantling power structures in the public realm is unimportant. She blurs the lines between public and private life, creating space for a middle ground that is revolutionary and provides objectivity. She is able to seamlessly connect how personal life and experiences, allow institutions of oppression to flourish in public life as systems of power and domination. Her story and work lay as a testament to this. Experiences in her personal or private life gave her the tools necessary to start a revolutionary movement.

This is what is radical about this movement – the long overdue objectivity that is now being given to the lived experiences of women, specifically lived experiences with sexual violence. For centuries, the narratives of women in India have been discarded and unrecognised. This was exemplified in 2017 when men’s right activists in India gained a ‘victory’ when the Indian court ruled that men had to be protected from false claims of domestic violence. The issue raised here was essentially that women are liars, thus ‘unobjective’, deeming accusations from women as unreliable.

Our patriarchal society denied the rights of objectivity to the stories of women who are often relegated to the realm of spirituality and domesticity and thus deemed as irrational. Our voices, our narratives have been hindered from entering the public sphere and are thus not considered in making policies that directly affect us like policies surrounding sexual assault.

Burke made me realise that the allowance of rape culture in private life i.e through your home, friendships etc allow public structures of oppression to go unnoticed. Let us take for example the recent exposing of Nana Patekar as someone who is a perpetrator of sexual violence. As the events were brought into light, we also found out that his behaviour of violence were no secret in the industry. Yet systems of patriarchal power allow his behaviour as a sexual predator to be neatly placed in the private realm still giving him credibility as an actor.

What the #MeToo movement did was give Tanushree Dutta’s narrative and lived experience an objectivity that can be carried into the public realm and thus be seen as a valid reason to hold Patekar responsible of his crimes. Thus, replacing Patekar from film’s he was previously a part of becomes a radical and validating response to Dutta’s lived experience. This rhetoric empowers women to resist ‘mundane’ experiences of sexual harassment that have become the norm in our society. This rhetoric allowed me personally to validate my own story.

Also read: One Year of #MeToo In India: Stories We Tell And A Lifetime of Lessons

Up till now movements to end sexual violence against women and other marginalised identities have focused on the dismantling of this power structure that exists and is visible in public life. Burke however, claimed that she would feel accomplished when “a survivor of rape would feel whole again.” Burke by putting emphasis on emotions and turning the narrative around from the perpetrator to the empowerment of the survivor, highlighted the irreparable damage that sexual violence does. It put equal emphasis on dismantling power structures through public life and dismantling the insidious functioning of power structures like the patriarchy, that takes place in our everyday life.

Featured Image Source: The Daily Texan