Ismat Chughtai, in her memoir of Manto known as Kaghazi hai Pairahaan, says, “His (Manto’s) stories unsettle us because they take us to the darker, brutal corners of our psyche, to desires repressed and ugliness that settles.”

Which seems so true once we start exploring the emotional layers within Manto’s writings, where he wrote extensively about the twisted and dark corners of human psyche at the backdrop of partition. In times like these where reality is too hard to bear, when we either try to insulate ourselves from socio-political realities in order to not become ‘too political’, or we turn a blind eye because that’s an easier way out anyway, reading about Manto and his afsaane (stories) is a challenge in itself, because it questions way too many complexities of life, of society, of your own privilege, while stirring the very core of our innate emotions. Manto speaks directly to our emotions, and his writings create anxiety amongst those who tried their best to preserve the status quo.

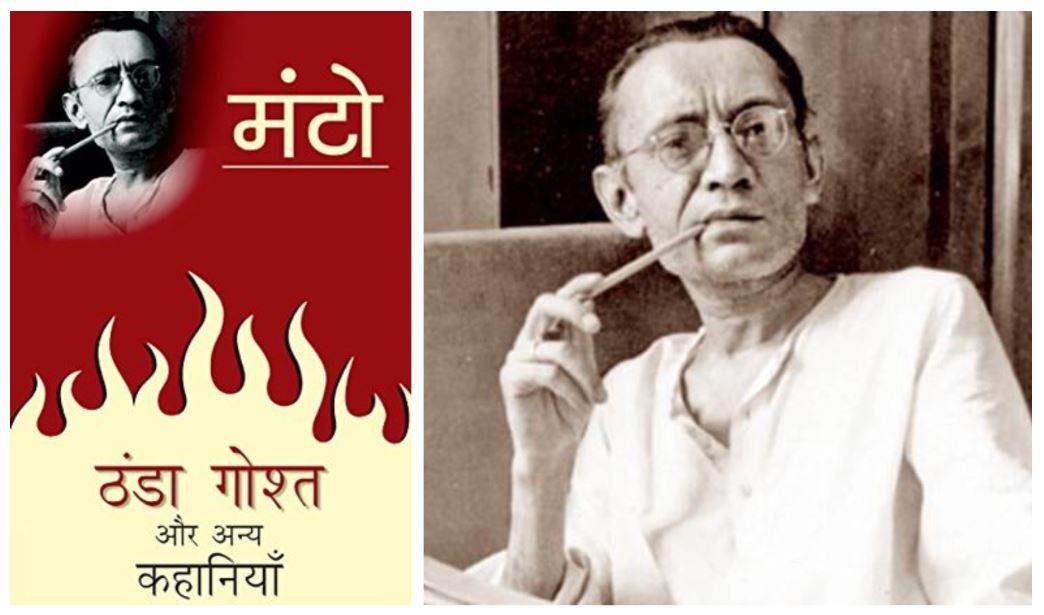

Also read: Why ‘Manto’ Continues To Be Relevant Today

While drawing the juncture between religion, national identity and patriarchy quite skillfully in almost all of his short stories, Manto tried understanding the political underpinnings of female body, over which communal hatred was played on. The intersection of gender-based violence with religious hatred in his stories point at the grim reality of society where female bodies are still used to inflict violence and showcase the domination of power of one religious sect over the other. There’s a prevailing idea of deriving pleasure by inflicting pain on the fellow individual who belongs to a different community.

The rape of a corpse is symbolic of the blindness of exertion of power and control, not only over women, but also over members of other communities.

Thanda Gosht (Cold meat) is based on this idea, and the story comments on the extent of violence of rape, by rendering the perpetrator, impotent – because he attempted forcing himself onto a woman who was dead. The perpetrator, Ishar Singh, is depicted to have experienced not just the physical pain of being attacked by his wife, Kulwant Kaur, but also the psychological trauma of attempting to rape a dead body. The very fragile nature of toxic masculinity is exposed from within the character of Ishar Singh and the writer symbolically tries to depict the psyche of the rape victim, by making Ishar Singh undergo physical, psychological, emotional and sexual trauma, and reducing him to just a lifeless piece of meat as the story ends, similar to the lifelessness of the corpse he attempted to rape.

Thanda Gosht also points at the pointlessness, the ‘impotency’ of the very nature of communal hatred itself, because it leads to no end. The barbarism of communal conflicts, evident from the aftermath of partition, led to extreme loss of life and property, and a damage so deep that we are, to this date, struggling with its repercussions. The rape of a corpse is symbolic of the blindness of exertion of power and control, not only over women, but also over members of other communities. Such vivid, ugly and heartbreaking depiction of stark socio-political realities makes Manto’s stories extremely relevant in times like these when women’s bodies are made sites of war to exert violence and patriarchal control. Even in Khol do, Manto juxtaposes the idea of gang rape of a woman with that of humanity.

While writing about the abhorrence of partition, one quite interesting aspect about his stories was the way he represented women. Manto carved a space where women are trying to negotiate their voices within the patriarchal setup.

Manto never took a moralistic standpoint through his stories. In fact, he was a staunch critique of moral binaries of the society which gave them a convenient escape to stay in denial and ignorant about pertinent and problematic issues, especially for women within a patriarchal framework. While questioning the very idea of moral framework set by the society, Manto recognised the institutional framework which is responsible for not only laying out the ideas of morality, but also using it as a means to perpetuate misogyny, to which even the male characters in his stories are a victim of.

His female characters remain assertive, exercising their sexual agency and questioning the bodily control they have been subjected to. Women in Manto’s stories were the outcome of an imagination where they would assert their beings, remain unafraid and claim spaces which are rightfully theirs – spaces where they belong. He recognises systemic oppression of women through institutions, which is why he sees both a homemaker and a prostitute as victims of institutionalised misogyny; and presents them without inserting a moral code of conduct. At the same time, he is also looking at the emotional void which has engulfed them.

His female characters remain assertive, exercising their sexual agency and questioning bodily control they have been subjected to.

His writings beautifully depict the poetics of sadness. Sadness which has feminine undertones. Sadness which just doesn’t remain in her eyes but is channelised through her anger, and within this anger lay plethora of questions challenging all the shackles which have been around her. Sadness which is personal to the lives of these women characters but hugely political because it stems from the patriarchal system.

Manto’s male characters, on the other hand, are often seen exposing their vulnerable, delicate, sensitive sides at the backdrop of something as harsh as partition which is constantly pushing them to adhere to the toxic masculinity.

Manto also used his female characters to sensitise his readers both towards human condition and conditioning. His stories didn’t just bring out a whole different way to look at the female condition, but there was an innate femininity in his writings, too, which would demand tenderness towards the brutality and pathos of partition and the cynicism and the indifference associated with the ideas of togetherness and faith when there was nothing but bloodshed.

Seeing how patriarchal regressiveness is played over and controlled by hyper nationalistic sentiments in times like these, Manto’s relevance cannot be underplayed even to this date.

He isn’t just a writer who wrote extensively about incidences around the aftermath of partition. He is a symbolic representation of the dire need to have a humanistic standpoint- a need to be empathetic and be less in denial of the abhorrent realities of human society we perceive every day. It is no wonder that if Manto lived in times like ours, the charges filed against him due to obscenity in his stories would still have remained as is, if would not have grown worse.

Also read: Saadat Hasan Manto And His ‘Scandalous’ Women

Perhaps he foresaw his own relevance and how his writings would outlive him in politically turbulent times of intolerance, dissent and communal hatred when he said, “…and it is also possible, that Saadat Hasan dies, but Manto remains alive.”

Reference

1. The Guardian

2. Deccan Herald

3. News 18

4. First Post

5. J Stor

About the author(s)

Tatsita is a postgraduate in Public Policy and Governance from Azim Premji University. A film and cultural studies enthusiast, Tatsita is fascinated by the Marxist, Post-Structuralist, Post-Modernist and Psychoanalytic school of thoughts to understand the idea of power in complex human relationships as well as oppressive social structures around gender and caste. Her interests also include film editing, sociology of law and intersectionality of urban housing patterns in India. She can be found on Twitter.

A correction: kaghazi hai perahan is Ismat’s memoir in which she mentions Manto.