An English teacher I once had would often repeat her favorite adage – something about “not just growing old but also growing up”. In many ways I can say I did not start feeling like a grown up until I was well into my thirties. I share my story and findings in the hope that, through this, I can connect with some others like me who may have been asking similar questions.

As a researcher who routinely uses ‘postmodern feminism’ as an exploratory lens, for her work, I am asked, almost as routinely, for its meaning. In the past I proceeded to give long winding and seemingly arrogant explanations until I realised that this did not work – for me or for the questioner/listener. If only for the sake of argumentative coherence I would like to give this explanation another try but this time in writing.

The first thing that one learns as a beginner in the postmodern research world is the importance of ‘speakability’. Not just in terms of what can be spoken but also, who can speak it. So in essence – it is not just what is ‘allowed’ to be said but also by ‘whom’ is it ‘allowed’ to be said.

So in my conversations I started becoming quieter – quite difficult for an extrovert such as myself. For I wanted to listen to what was being spoken and who was saying it. This is a wonderful exercise – not just being silent but being attentive to the setting. So when a coal mining and electric company’s CEO delivered a talk at my alma mater – it was replete with words like “rich resources”, and “plenty of jobs for areas where we invest” and completely lacking in all discussion about the importance of natural conservation.

It was the first time I realised the magnitude of this idea of ‘speakability’ and the extent to which it permeates our lives. For I realised as an ardent user of electricity and living inside a concrete ‘vista’, I found it difficult to speak of natural conservation without realising my own double standards.

Thinking about this many times over in several contexts, I started seeing it everywhere. Unspoken ‘rules’, almost as a ‘common sense logic’, about every single thing we think, speak and do during our lifetimes. This is one of the foremost things one becomes observant about – who can say what. And why can’t we say certain things? The ‘saying’ not only refers to the verbal speaking of something but in many cases even a mere admitting of it to our own selves.

Why can’t I, for instance, ever say to myself that I do not want children – without adding the qualifier ‘maybe’? Why can’t a friend I know who is a father of two, admit to the difficulty and tediousness of childcare and insist that he genuinely wishes to be a substantive part of his children’s lives and therefore give up his job? Why can’t he retire in his early thirties, leaving his wife to be the sole-earner? Why can’t I say positively and with surety that I am happy being ‘unmarried’?

I realized much later that it was in fact about ‘speakability’ and about this dispersed nature of power.

Some of these questions need not even be answered to someone else or in public. We need only admit them to ourselves – so at least we have a clear conscience. But what is it that prevents us from answering them with genuineness and honesty? Is it the same ‘common sense’? Where does this ‘common sense’ come from? Are these the rules? If there are, who sets them? This, I believe, is the question that postmodern feminism has led me to investigate.

I realised through reading a plethora of feminist scholarship – among them those of Michel Foucault, Carol Bacchi, Deborah Stone, Judith Butler, Wendy Brown and Bronwyn Davies – that what is ‘postmodern’ about this idea is its characteristic of being ‘dispersed’. This authority is not a central figure – it is not the government or an oppressive religious regime. It is rather a matrix of power in which we are held together, suspended as though in a spider’s web of different narratives. So we cannot quite isolate one cause for this feeling of ‘loss of autonomy’. Because there is no salient all-powerful force that dictates this common sense. Sometimes in search of the answer to “What is stopping me from saying it – even if to myself?”

We could be led to various options – viz. pressures from family, friends, bosses, co-workers, spouse, children, parents, the police, the law. Other times the answer would just be, “that is how it is”. This logic we seem to employ so often and effortlessly in ours lives – is what is dispersed power. It is in our everyday lives that we find this capillary power (as Foucault describes it). So it was postmodernism that led me to understand that power is everywhere. But what is ‘postmodern feminism’ like? Where does it lead us?

Earlier on in my research career, I believed that women who work have more agency in their domestic lives. Similarly I believed that upper class women such as myself – should make a political statement – and never stop working. And that they should demand that their spouses share equally in childcare. Equally so, some women I know, believe that women who have children must not relegate them to nannies or daycare just because they can afford to. They must take the time to carefully craft the child to being a good person because this is hard work and it is as essential as it is painstaking.

In another example I once, simple-mindedly and rather foolishly, asked a trans friend why trans women were upholding the beauty standards created for cisgender women, when they could instead – provide so much insight about the falseness of gender and testify to how ‘gender’ is a massive hoax.

I realised much later that it was in fact about speakability and about this dispersed nature of power. Trans women, as I learned, live in fear of not ‘passing’ as cis women. Not ‘passing’ would mean being alienated as an ‘anomaly’ and it would most certainly for the trans women I know – mean violence. We do not yet live in a world that sees people as just people. And until we continue to inflict social sanctions (and even physical ones) on people around us – for not fitting our particular standards – we cannot expect for trans women or any other marginalized community to feel safe in our society.

In addition, feeling like one’s own self is something all of us can associate with. I wouldn’t give up even the side on which I part my hair. When the minutest of such salient features are so precious to me – how could I not see the pride in presenting oneself as one wishes to? The speakability of calling oneself a ‘woman’ (whatever that means) is not afforded to all women alike. Hell even those of us cis women with a slightly deep baritone in our voice or with facial hair, are treated ‘different’. Was I thus really understanding the variety of ‘dispersed powers’ that my friend had to deal with as a trans woman?

Similarly, in my example of childcare and working outside the home. How can we really attribute what others are doing to a ‘bad politics’? We each walk and balance on a thin wire of this capillary power. Any speech or act can and often does mark us ‘different’ and there is no reason for me to claim that I know better about other people’s choices – childcare or work outside the home. Apart from just the regular pressures of class, caste, religion, sexual orientation, physical ability, and many more. there are innumerable forces one may have acting upon them.

Also read: Is Impostor Syndrome, Or Feeling Like A Fraud, Gendered?

I am a PhD student and so the fear of professors and their politics is real. Being fat, the fear of asking for a second helping is real. Being a feminist, the fear of being mocked inside a classroom for something I have said, is real. Being a qualitative researcher, the fear of asking questions in a quantitative research presentation, is real. Amongst all these forms of power in our everyday lives it was postmodern feminism that explained how I could worry about equality and structural issues of gendered segregation of labor and sexual violence, whilst understanding that no one is free from the clutches of patriarchy.

Any speech/act can mark us “different” and there is no claiming that I know better about others’ choices

It helped me see that commenting on the nature of other people’s and other fellow feminists choices was not going to deepen my understanding of the different forms of capillary power, which are present in my life. Only by being a studied and mindful observer of myself, will I be able to see how my ‘choices’ and values are shaping and being shaped by – my social surroundings.

Thus we may often use big words such as ‘hegemony’ to define these forms of dispersed power, when what we really want to do is to urge the readers of our work, to ask questions exploring the ‘what’ in “What stops us/ does not allow us to speak or do what we wish to?” So I began more often to ask myself this question.

I began to uncover an interconnected web of social structures/ norms/ values/ beliefs that were being enacted through the people in my life. And I also started appreciating that different permutations of this ‘interconnected web’ are acting in the lives of all those around me. And most importantly – that many of these forms of power were acting through me. By upholding and performing certain values and beliefs – I was ensuring the presence of these forms of power in my own life as well as those of others around me.

However one caution here is to not start attributing everything to a mythical ‘hand’ that ‘capillarises’ this power (be it of capitalism or patriarchy) and thus absolving individuals of responsibility. Yes we are each to answer for any injustices we have committed onto others, and ourselves but in every account of injustice – I believe it is important to account for and introspect on the narratives that we allow inside our lives. Which forms of capillary power have been enacted through us onto others? How are we discriminatory? How do we judge others around us? What beliefs and values do we let known? What do we say? When do we say it?

Also read: Can We Stop Being Scared Of The F-Word Now?

I speak therefore, of the cultivation of this questioning mind. And questioning not only content, but also values. Vetting not only on merit but also on beliefs. Understanding not only others but also ourselves. That is perhaps what postmodern feminism can offer us, should we wish to take it.

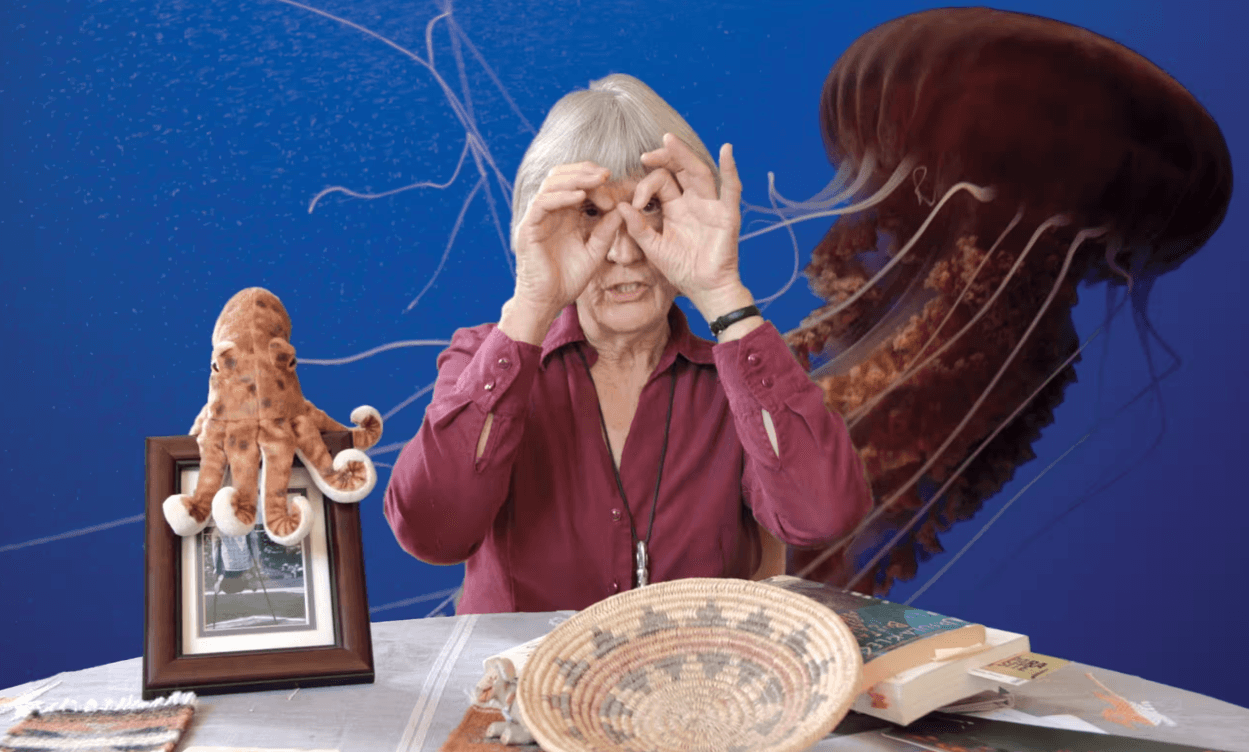

Featured Image Source: Yucatan Expat Life

About the author(s)

Mahadevi is a researcher in critical gender and policy studies and uses a postmodern feminist lens to look at issues of marginalisation and violence and how these structures are produced by everyday practices, norms, values and beliefs.

Hi

I must say that this is an interesting piece, but I have a few questions. I’d love to discuss this with the author directly, but any/all answers are welcome.

1. ‘Speakability’, as is defined, seems to operate in the multiple cases outlined above. But is it similar in all the cases? Is the ‘unspeakability’ when we (do not) talk about natural conservation the same as when we (do not) talk about sexual violence, trans rights or caste relations? I’d assume that the motivations (or its absence thereof, which suggests hegemony) vary greatly across the board.

TL;DR, I am arguing that not all examples fit the narrative as cleanly.

2. I understand what you are saying about capillary power, but why do you emphasize so much on acting this power and not on being due to this power?

3. The notions of ‘speakability’ and dispersed power exists in materialist feminism as well. What separates it from its postmodern counterpart?