Posted by Aroh Akunth

Last Sunday TISS Mumbai observed it’s first of a kind festival which centred the works and narratives of artists coming from SC/ST/OBC and other marginalised backgrounds/art forms. 30 artists consisting of academics, writers, poets, film makers, cartoonists, puppeteers, painters, photographers, dancers, musicians, and theatre practitioners from 10 states were present at the festival.

The lineup included well known names such as Urmila Pawar to highly awarded but lesser known artists who have been working for their communities and movements as cultural activists along with aspiring artists and students. We decided to do a feature on questions which are often asked of us when we go about organising festivals such as Bahujan Arts Festival alternatively titled Marginal Art Festival.

Why the title?

The festival title is purely a creative choice – very much like ‘Begumpura’ inspired by works of Gail Omvedt or Dalit Art Festival which talked about Dalit artists but also featured artists from other Bahujan identities. Neither have we made nor do we feel there is any relationship between the word marginal, which has been used as an adjective with art and shouldn’t be read without it (or Bahujan). For us, it was more about access. Bahujan is a word which implies majority. It is an assertion, adjective, oppositional practice and resistance among it’s many meanings.

Also read: Chennai Organised A Queer LitFest For Writers and Artists In The Margins

As a political imagination it has sought to challenge the upper caste dominance which is often masculine/feudal in nature. Anybody who is not an upper caste Hindu can lay claim to being a part of this purported 85% population. Bahujan as a form of politics is very accessible to Hindi speakers and people familiar with anti-caste politics. But as organisers, we were aware of individuals coming from the same social position as us who might not be coming from the same experience/ideology but might go through the same kinds of oppression in everyday life.

A lot of our audience may not be Hindi speakers or identify as Bahujans even though they are SC/ST/OBC. We wanted this platform to be identity centric and accessible for even non Hindi speakers, as we believe all our artists face similar structures of caste irrespective of their familiarity/ exposure/ experiences with anti-caste movement in their artistic endeavours.

Marginal Art, in the title doesn’t refer to the people but the art they create. The festival wanted to make a strong point about how art created by our people is either appropriated, museumised, or doesn’t make it into mainstream. It is also about art forms which have been historically marginalised in communities such as nats, devadasis and others which bring with them challenges of inclusion for the larger movement and people who define discourses on art and culture.

“These are some drawings of my vision of how our ancestors may be. I wanted them to look like our people and be fierce, present, and peaceful. Some of the faces are based on people who are beautiful in my life. These drawings are meant to add visual representation to dalit, adivasi bahujan lineages , divorced from their Caste-d , earthly lives, dignified, liberated from Brahminical imagination”, notes Maari.

What does the poster stand for?

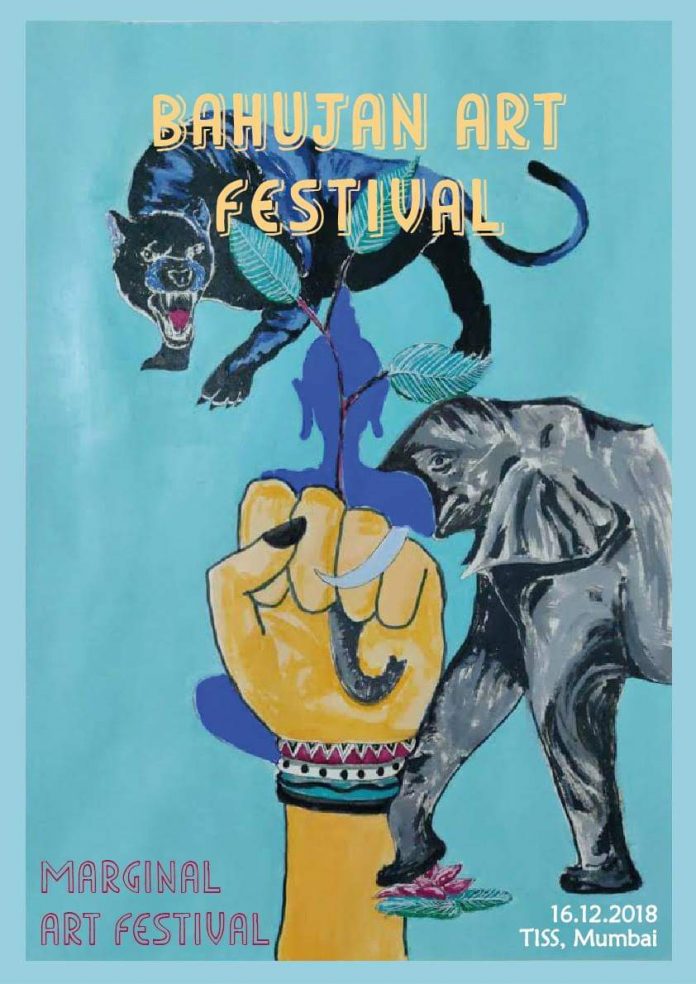

If we were to explain the poster, it would spoil the fun. We wanted to keep it visual that was for sure. The poster features a rising fist from which we see a plant sprouting, it is a nod to our agrarian roots and struggle for authority over our own land. The hand is jewelled in patterns you will see in many indigenous art forms, appears feminine, but hands do not have a gender. The panther is a reminder of the anti race, anti caste struggles. The elephant crushing the lotussymbolises desire. The Buddha icon is a spiritual, political, economic, philosophical and cultural imagination which many of us might subscribe to or draw from. A big shout out to design team of Jonah, Srishti and Karanika for realising the idea on a poster in record time.

Why we organised the festival?

When we are asked this question, it is difficult to reply in a one word answer. One cannot stress enough about the kind of exclusion one faces as a Bahujan artist not only in terms of intimate violence but also in the way we don’t see many Bahujan faces occupying media and entertainment companies. Or even artists being represented in mainstream commercial art festivals/cinema which do not cater to them. Even if one is invited to such festivals it comes at the cost of having to modify what one can say or perform under the upper caste gaze.

We do not lack content, but often the ‘means’ to make it reach to the larger audience.

Our artists especially, a lot of times come from communities which have been relegated to that job, or even if they have chosen to practice their art forms, it becomes difficult to pursue due to economic, linguistic, socio-cultural and political barriers. All these events stressing on amplifying exclusively Bahujan artists are born out of the thought to have a platform of our own, they have intentionally avoided being named under any particular organisation or being held in a particular institution so that they continue and are free to be replicated in various campuses by SC/ST/OBC students coming together.

It allows our artists also to exchange ideas, network and talk about their issues. We firmly believe that art is something around which community can be built and artists can sustain other artists. This festival’s theme was that of self sustenance or whether it is even possible for our artists to self sustain. Our festivals have also discussed modern, expensive and often inaccessible forms of arts such as filmmaking and the dynamics of digital media and are central in their planning and execution. We are setting them apart, if such a distinction is to be made from our regular celebrations of art, culture, and identity.

What is it’s significance?

We believe it is in art that allows us unparalleled political imagination, and even in sessions where many of us talked about the immediate violence in our respective work places and institutions, art allowed us to make something cathartic out of something negative. As students and even as individuals it is especially important for us to explore such platforms. We do not lack content, but often the ‘means’ to make it reach to the larger audience.

Also read: The Aravani Art Project: Inclusivity & Art With The Transgender Community

For this purpose our definition of artist was also someone who wants to create art and many of our students took part in such an initiative for the first time. With this our imaginations of audience, how art is experienced and what constitutes art was also challenged. Where political movements against Brahmanical university structures which we have come to recognise as upper caste dominated Agraharas are essential, we need such cultural interventions to sustain our discourse.

Aroh Akunth, has done their Bachelor’s in Social Sciences and Humanities from Ambedkar University Delhi. They often write about their experiences navigating caste-queerness and are a theatre practitioner. Currently, they are pursuing masters in criminology at Tata Institute of Social Sciences and are the cultural secretary with the TISS Students’ union. You can follow them on Instagram.

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.