I wanted to enter unannounced; my need for silence intensified by the increasing decibels of everyday life. Although a Hindu temple is hardly the place for accomplishing such ambitions, I let myself into thinking it might be too early for the cacophony to begin. My increasing ideological differences with this space has never impinged upon what I have always thought of as a personal relationship with the spirit who inhabits idols, an idea, sown in childhood, which transformed with time. While in childhood, I would be part of the loudness that came with this notion, now, I feel the bond between us is more of silence, for the need to calm down. I closed my eyes hence, to feel that within.

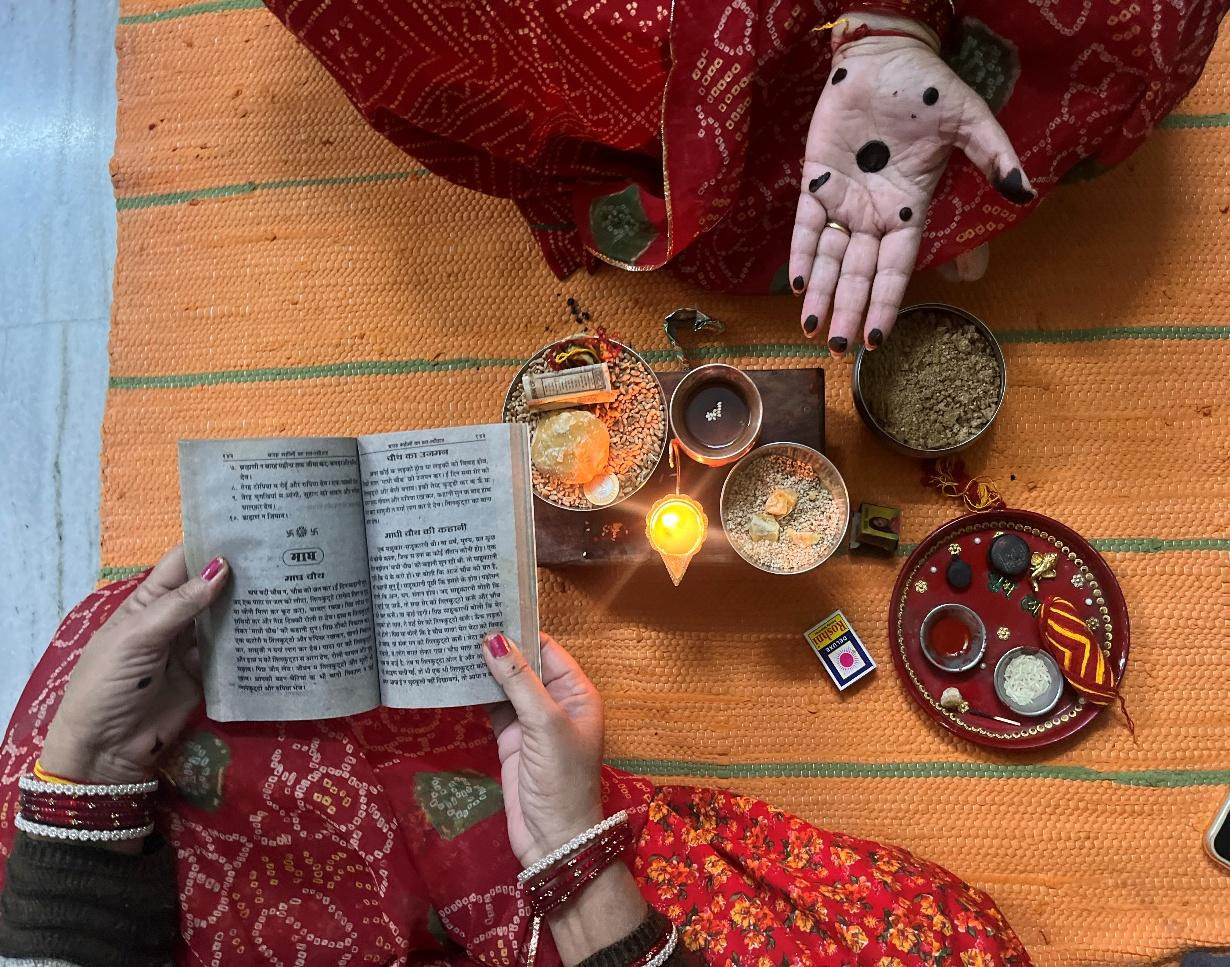

A clang of the gates pierced through that coveted silence and I opened my eyes to humming voices, rustling sarees, jingling bangles and jangling plates. I turned around to find a group of freshly bathed, wet haired, cotton-saree clad women walking into the temple with plates full of fruits, glasses of milk, incense, clothes, flowers and the mandatory sweetmeats, without which worship remains incomplete and the prasad less desirable. They put their bhog, the food-offering to the goddess, at threshold of the gorbo griha– the place inside the temple where the idol is situated. No one other than the associate of the priest, mostly women, and in some orthodox places only men, and wealthy patrons have the privilege of entering there, thus discrimination making its way into a space where equality of all before the One is supposedly the norm.

Throwing a glance at me, where I thought I could discern dismissal, the women got busy in arranging their offerings. Although of different age, the uniformity in the arrangement of those plates indicated how intensively rituals percolate through women who must bear the obligation of being the conserver of home, a space that often deprives them of their rights and offers less choices.

While the authority of men in carrying out Hindu religious rituals is not unknown of, it might be interesting to note that, pancha devata, the five deities who are invoked before every worship includes Parvati, the goddess of Shakti, a woman without whom no pujo can begin. Yet, women are debarred from temples; they are made mere facilitators for the trickling down of rituals. A woman can either be a devi, the giver or or a devil, the deviant woman. Since giver is a naturalised role for women, women can act as the medium of taking the prasad to and fro, between the bhakt and the bhagwan, although the pujo is usually never offered for women.

The bhog bears the name or gotro, the caste name, of those she stands as proxy for, the husband, the children or the father. Often among Bengali Hindus, a bhog is offered in the name of the eldest male in a family, as he is considered the transferor of identity. The wife, who is the vital medium of such transference, remains obscure.

Women who wear it by wish or by force to keep up to traditions remain out of discussion. But women who abstain from it are bitterly dismissed as ‘modern’.

While a child still remains the sole responsibility of a mother, she is barred from all joyous activities of her child’s life. A Bengali mother cannot witness her child’s first rice taking, or even her wedding due to the ritualistic prejudice that a mother’s sight could invoke the inauspicious. While the groom’s mother is left in an almost deserted house, the bride’s mother must remain invisible during the marriage rituals. That marriage is primarily a family extension programme with executive responsibilities vested on women can be realised from the fact during the day’s rituals a daughter listens to shoshthi broto kotha, a religious tale about the bounties of Goddess Shoshthi, who is the goddess of reproduction.

While women must bear all the implications of these rituals in their lives following marriage, a mother is not supposed to cook any meal for her pregnant daughter during her baby shower. Women are made to dwindle between being a grihalaksmi, the home-maker and the bearer of ill-fate, according to these self-contradicting ritualistic norms. Yet these rituals unscrupulously seep into households, especially through women, who show no resistance to that which is burdened upon them in the name of tradition.

In another obnoxious custom the groom, while setting out to marry, must whisper into their mothers’ ears, “Maa tomar jonno daashi ante chollam” (Mother, I go to bring your slave). Marriages have, along with stitching together sagas of love, being harvesting unequal power relations. Patriarchal attitudes help camouflage such traditions from time to time under the guise of something non-serious. Anything that involves degrading a woman’s dignity can be passed off as a ‘joke’. Marriages are thus replete with such jokes. Incidents of resistances, although rare, are discouraged as spoilers of traditions and entertainment for the crowd, who must take back something more from the ceremony besides the menu card.

Thus the oppressive nature of local rituals continue to remain invisible as they are seeped into the universal narratives of rituals. Mediatised attention tend to make them glamorous moments of indulgence which subtly gloss over their oppressive nature. As I noticed the vermilion stained forehead of the women in temple, where the clamour had increased, I thought how this ritualistic endowment hardly considers the choice of a woman. Women who wear it by wish or by force to keep up to traditions remain out of discussion. But women who abstain from it are bitterly dismissed as ‘modern’.

Brahmin women are called in to prepare onno–bhog (offerings made of grains), a privilege denied to women of other castes.

Again, the glamour that is associated with vermilion stained foreheads, especially of a newly-wed woman or during shindur khela in the last day of Durga pujo create ambiguities regarding this ritual. In fact sindur khela is such an over-hyped affair that it deftly disguises the segregation it creates on this last day, may be bringing back moments of tremendous pain for those who must be keep away from it – widows, divorced or any such women who cannot be associated with a husband.

On this last day, Durga is celebrated as a wife, a mother, a provider with much greater fervour than what the previous days’ frenzy could add up to. Conveniently marked as a space where women are to celebrate themselves, they are extolled for a socially and culturally sanctioned relationship that define them through men. This ritualistic observation should be about choosing – the hype, completely abandoned.

Also read: Meitei’s Biggest Festival ‘Ningol Chakouba’ Is A Celebration Of Its Daughters – But Is That Enough?

The women in the temple were visibly upset. The priest was late and they were hungry. Of course, since worship meant giving up of self, inflicting pain to the body through fasting is the most acceptable way of doing that. It suddenly struck me that going by the well-known Bengali idiom ‘baaro mashe teyro parbon’ (thirteen rituals in twelve months) which humorously ridicules the excessive involvements of Bengalis in rituals, for most women fasting must be a daily affair.

While Tuesdays are reserved for different versions of mangalchandi pujo, every Thursday Bengali households reverberate with sounds of conch shells and ululation to the tune of Lakshmi panchali. There are other weekly rituals, which receive less media attention, to keep Bengali women busy in invoking deities. The intermittent celebrations continue – Shasthi pujo, popularly known as jamai shashthi, Beepodtarini pujo that comes with Rath yatra, Manasha pujo, Neel pujo, a Shiv pujo variation – and the list continues. And with this fasting continues for women who end up being troubled by an endemic gastric problem.

These observances often receive institutionalised support, finding space in government holiday lists. If national festivals are left aside, holidays are granted for local rituals which often tend to become vehicles of pressurizing working women to create a work-life balance.

While urban metropolitans can ride on the wings of progressive attitudes and consider such observances as disappeared, provincial towns, with their close knit, highly observant and judgemental middle class communities, still reverberate with such tales. Here women priests are impossible to find; women are barred from touching the Narayan – shila; Brahmin women are called in to prepare onno–bhog (offerings made of grains), a privilege denied to women of other castes.

While undue media attention allows certain rituals to go on with unquestioned orthodoxy, these everyday rituals and their steady percolation down the line through women tend to deny women an understanding of choice. The categorisation of those like me as hyper modern dis-believers do not allow the creation of a space of secluded practice of religion without the accompanying noise, thus again foreclosing spaces for reasoning out.

Also read: Indian Hindu Festivals: No-Win Situation For Women

Religion becomes a jumble of reiterating soulless practices that oppress and do not allow the understanding of religion to surface. Understanding that the community is yet to eke out a third space for silent believers like me, I realised, that although emancipation has allowed women to resist in various ways, and of course, the contingent moments of emancipation stand undeniably to flag progress, there are such innumerable invisible issues which tend to become so assimilated into our everyday lives that trying to unpack them would continuously direct our attention towards the notion of empowerment as an unfinished project.

Featured Image Source: Money Control

About the author(s)

Priyanka Chatterjee is a mother, researcher, and academic. She lives and writes from Siliguri. Her articles have appeared in Feminism in India, LiveWire, Himal Southasian, Sikkim Express, among others. She can be reached at site.surferpc@gmail.com and is on Instagram @priz_chatt

Well written. Interesting read.

There are so many conceptual mistakes in this article. These articles take the whole women empowerment in a completely wrong direction. If the writer wants I will explain where she has gone wrong. xx