Posted by Gayatri Devi

In Kerala, every single man and woman who protests the entry of women of menstruating age at the Sabarimala temple has personally benefitted from the presence of a menstruating woman in their lives: their own mother. They were conceived because their mothers menstruated. The mothers gave birth to these individuals, so they can be out in the streets barricading women of menstruating age from the Sabarimala temple. Think of that for a second.

This current hysterical flap against youthful women is a good opportunity to revisit the relevance of menstruation in the human life cycle. Even though Monty Python sang that “every sperm is sacred, every sperm is great; if a sperm is wasted, God gets quite irate” in The Meaning of Life, statistically speaking, men produce a vast quantity of sperm during their lifetime and shed several millions of them each month. Women have a reserve of about 400-450 egg follicles as they hit puberty with each follicle producing only one egg or ovum, each month. If it is not fertilized by meeting with a sperm, the body releases this egg through menstruation.

We have been told that the divine Ayyappan, or Sasthavu, as I knew him, does not like youthful women worshipping at his temple because of their menstrual pollution. However, the legend of Malikapurathamma, the goddess shrine at Sabarimala, Ayyappan’s alleged unrequited lover, and the customary recruitment of ‘Kanni Ayyappan’ (literally ‘virgin’ Ayyappan –young boys making their first pilgrimage) point towards Sabarimala as a homosocial space where women are intentionally not welcome. This ejecting of youthful women from Sabarimala is a manufactured exclusion to keep women out of a purportedly homosocial male space.

However, menstrual taboos among certain communities have assisted this pollution charge against menstruating women. Though the menstrual blood flow comprises of fresh blood, clotted blood and endometrial tissue from the lining of the uterus, it has become questionably “traditional” to assign a ‘polluted’ or ‘impure’ status to menstruating women among certain communities.

Anthropological and ethnographic studies show almost a totemic worship of the young menstruating girl as an aspect of Bhagavathy or Devi, the primordial mother goddess.

The vernacular Malayalam word ‘theendari’ describes a menstruating woman with an ‘impure’ status. It forbids her from coming into physical contact with other members of the household, entering the kitchen, touching the cooking utensils, touching potable water, or entering the temple during her monthly period. ‘Theendari’ is referenced by informal terms like ‘purathavuka’, ‘veliyilakuka’, both connoting ‘being outside’ or ‘removed’ (from the daily affairs of living).

But ‘theendari’ is a cognate of ‘theenduka‘, a Malayalam word which means ‘to touch’ with the additional semantic intent of ‘to pollute’. We hear this meaning in the phrase ‘kaavu theendal’ for the ritual pollution of the shrine during the Kodungallur Bharani festival. Pollution was proxemic in application. The ‘polluted’ person had to keep an arbitrarily decided distance – 12 feet in some cases – from you not to ‘pollute’ you. 12 feet? Why not 11 or 13 feet?

Also read: The Vicious Circle Of Menstrual Taboos

All of this is ironic given the fact that up until two or perhaps three generations ago, in many communities across India, and certainly among the Nair community that I am most familiar with, the onset of menarche –the first instance of menstruation – was celebrated with great splendor.

Malayalam uses various terms for menstruation with each term carrying its own slightly unique semantic variance and valence. The clinical term aarthavam is for medical or formal registers. Aarthavam, a cognate of the word ‘rithu’, indicates in Sanskrit and Malayalam both seasons and the transition of seasons, hence, change. In the context of women’s reproductive cycle, ‘rithu’ or ‘rithukalam’ signifies the sixteen days from the first spotting of menstrual blood when the woman is most fertile to conceive. Thus ‘rithugami’ in Sanskrit and Malayalam is a man who has intercourse with a woman specifically for reproductive purposes. Somewhere in here is the semantic nuance of seed, flower, and flowering parallel to the processes of the natural world. All of those Malayalam film songs where the lovelorn male evokes and invites his beloved ‘rithumathi’ are sincere demonstrations of this mating instinct.

The vernacular choices for menstruation were ‘prayamavuka’, or ‘vayassariyikkuka’, both of which may be translated to mean ‘to come of age’, or the girl approaching reproductive maturity, and not necessarily sexual maturity. ‘Maasamura’ is roughly the equivalent of monthly periods. ‘Theraluka’ or ‘theranduka’ literally indicate a form of increase, or growth. All of these terms connote a positive valence for menstruation.

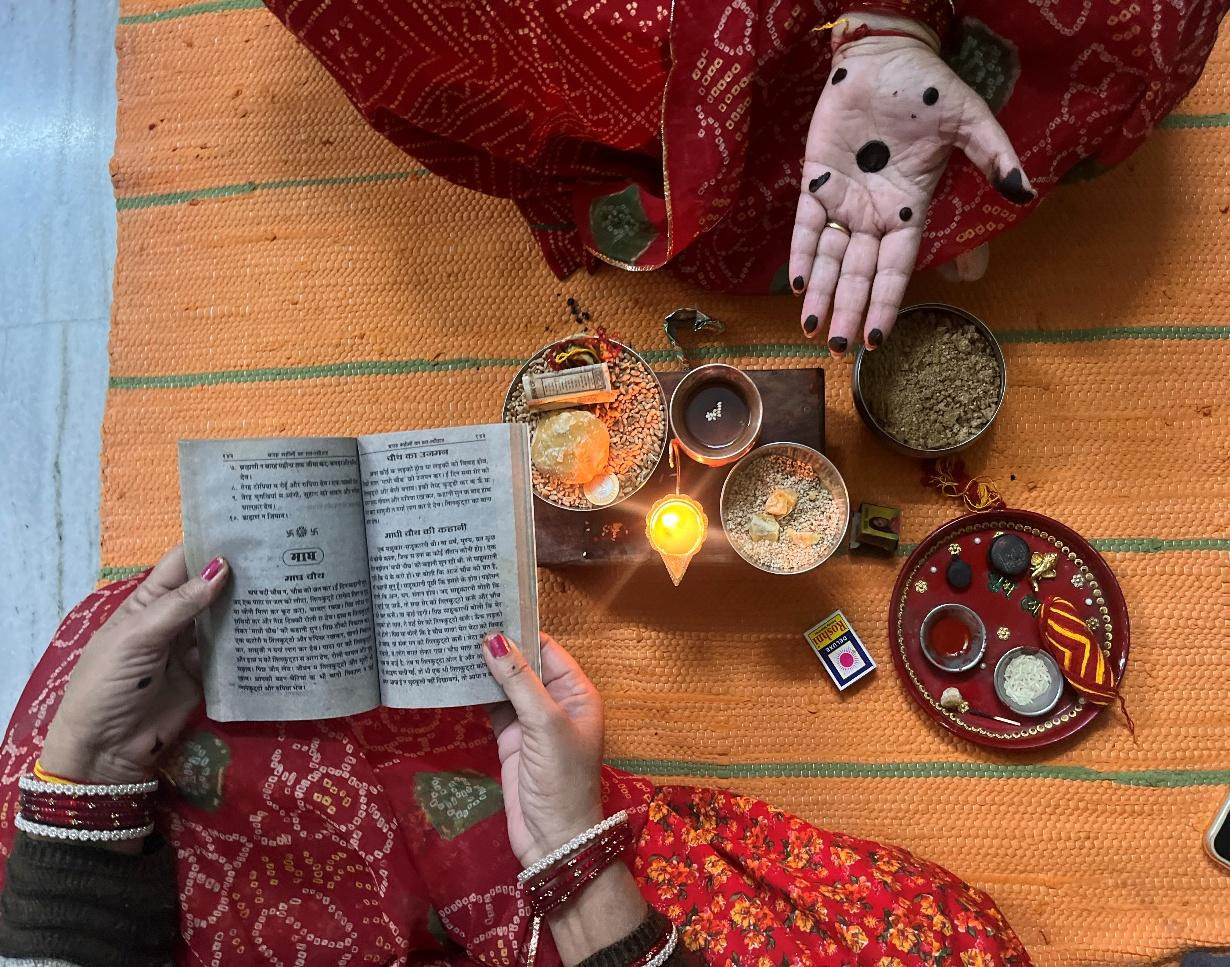

Indeed, the word ‘therandu kalyanam’ signifies the celebratory aspect of this liminal event in a girl’s life. Kalyanam in Sanskrit, Malayalam and Tamil indicates the most auspicious phase of a phenomenon. While not that long ago, Nair men and women engaged in ‘sambandham‘, a low-key selection of a conjugal mate, the young girls still celebrated ‘therandu kalyanam‘, or their menarche. Specific customs of ‘therandu kalyanam’ vary from community to community, but a common denominator was the marked positive familial and communal attention given to the young girl during this celebration. The young girl was ritually bathed by elders and presented with sparkling new clothes; special food was made for her, including sweet meats; and she was ceremonially set apart, not in pollution, but as a material expression of her state change. Her menarche was announced to the community. Anthropological and ethnographic studies show almost a totemic worship of the young menstruating girl as an aspect of Bhagavathy or Devi, the primordial mother goddess. The young girl now shared her female body with the goddess herself.

We all know similar stories of women who found themselves with their menstrual cycles on their wedding day and regardless went to the temple for their marriage ritual.

In Kerala, we have a Bhagavathy temple, where the goddess menstruates each month. In the legend of the Chengannur temple recounted in the Eithihyamala, goddess Parvathy was menstruating when she and Sivan arrived at Shonadri or Chengannur to visit Agastya rishi right after their marriage. So, they observed her ‘rithushanthikalyanam’ or menstrual celebration right then and there, which then became the site for Chengannur Bhagavathy temple. We all know similar stories of women who found themselves with their menstrual cycles on their wedding day and regardless went to the temple for their marriage ritual. No god or goddess has punished a woman because she menstruated inside a temple.

Chengannur Bhagavathy’s ritual menstruation or ‘tripputtarattu’ is celebrated in Kerala to this day. The goddess is confined to a special shrine during her periods to respect her power and not to punish her pollution. On the fourth day, the goddess is brought back to her main shrine with aplomb after ritual bathing in the tributaries of the Pamba river. Women (and men) who desire children, women who suffer from infertility, women seeking a good marriage all pray to Chengannur Bhagavathy. The goddess is real to her devotees because she menstruates.

Watching the mayhem unleashed at the protesting women in Kerala, though, I am reminded not so much of the power of Chengannur Bhagavathy, but the burning anger of Draupadi, the wife of the Pandavas in The Mahabharata. Draupadi was menstruating when she was dragged by her hair into open court after Yudhishthira, her gambling husband, stakes her in a game of dice with the Kauravas and predictably loses her. Yudhishtira had been on a losing streak, but that did not stop him from staking his wife in a gamble.

In the Sabha Parvam of the Mahabharata, the menstruating – rajaswala— Draupadi stands in the open court bleeding in her single robe and trembling in anger and helplessness in front of her five husbands and all the kinsmen. Dusshasana pulls at her singlet to disrobe this bleeding woman. But an epic is an epic is an epic, and just at that moment, Draupadi’s cousin and god Krishna steps in and extends the length of her singlet to infinite yards of clothing. Dusshasana is unable to strip her naked.

Also read: The Sabarimala Protests: History Repeats Itself As Progress Is Met With Violence

But there is no god Krishna in 2019 to step in and counter the attack unleashed against young women asking to worship at Sabarimala. So, another Draupadi comes to mind: the great Mahasweta Devi’s Draupadi, or Dopti. After the Senanayak of the Indian military and his deputies rape the tribal woman Dopti suspected to be a Naxalite and leaves her for dead, she revives herself and walks towards them. She pushes the Senanayak with her “two mangled breasts”, and asks them with a terrible laughter, “What’s the use of clothes? You can strip me, but how can you clothe me again? Are you a man? . . . There isn’t a man here that I should be ashamed.”

At Sabarimala, only the unbreakable will of the decent and progressive collective of men and women can stop this groundless assault on women’s autonomy to determine their social participation in all spaces.

References

1 “Draupadi,” Breast Stories by Mahasweta Devi

2. Puranic Encyclopedia by Vettom Mani

3. Eithihyamala by Kottarathil Sankunni

Gayatri Devi is an Associate Professor of English at Lock Haven University, Pennsylvania. She can be reached at gdevi@comcast.net.

Featured Image Source: Mythri Speaks

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.

Mensuration is god gifted boon to female, by which the god create a world of Homo sapiens. so every individual should have a clear mentality, it’s not evil of society. and must respect them and cooperate.