Trigger warning: Graphic violence

Coming August 6th, we will witness, as a nation, our judicial system, police and the state continuing to fail the Dalits of Tsunduru in Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh for 28 years. Not for a year, not for a decade – 28 years! What happened in Tsundur in 1991 can be described as one of the most gruesome and vile premeditated attacks on Dalits, not just in the state of Andhra Pradesh but in the whole of India, since independence.

The dominant caste groups of the village, the Reddys and the Kapus, and the Dalits, have been vying against and accusing each other of several small crimes prior to this incident. This led to a social boycott of the Dalits enforced by the Reddys and Kapus, which disallowed them from entering the ‘upper caste locality’ and from working in their fields. In about a month, on August 6th, this escalated into a full-blown massacre of 8 Dalits (7 Malas and 1 Madiga) in broad daylight by Reddy and Kapu mobs from Tsundur, Valiveru, Modukuru and Munnangivaripalem.

Local policemen, acting on the direction of the upper caste folk, visited Malapalli (the Dalit hamlet in Tsundur) to ‘warn’ the residents of potential attacks, inducing them to immediately flee the area misleading them to the nearby fields where Reddy and Kapu mobs from 4 villages were, in fact, waiting with axes, iron rods, spears etc to attack them. The Dalits were all caught unaware when they were hounded by these armed men on tractors and other vehicles.

In the attack that followed, eight Dalit Jaladi – Immaniel (35), Jaladi Mattaiah (40), Mallela Subba Rao (35), Mandru Ramesh (21), Jaladi Isaaku (25), Angalakuduru Rajamohan Rao (24), Sankuru Samson (28) and Devarapalli Jayaraju (29) were brutally hacked to death by close to 300 Reddy and Kapu men. Some bodies were chopped up, body parts separated and stuffed into gunny bags, while others were left as is, with multiple stabs and wounds, and were all dumped into the Tungabhadra canal flowing by the village. Several others were chased, beaten, and tortured in different ways, as recounted by Dalit men who narrowly escaped the mob’s clutches and managed to return to Tsundur somehow.

The Dalit women who stayed back in the village could not completely grasp the magnitude of the attacks until some of the survivors went back and gave them an account of the incident. One of the Dalit women recalled how she had pleaded with the police to help the men out and save them from the Reddys but they brushed aside the request stating that they would be rewarded handsomely if they supported the Reddys while the same could not be said for supporting the Dalits.

Over the next few days, bodies were being recovered by the Dalits who went on a look-out for the men who went missing during the attack. All the bodies were traced by the Dalits themselves with no help from the police. It was only then that the police stopped denying that a major incident had taken place at Tsundur. By the time the corpses were found, they were heavily swollen and decomposed. The bodies were taken to Tenali government hospital and by this time, most of the Dalit families fled Tsundur and took refuge in Tenali.

The Dalits then returned to Tsundur to fight back and demand justice, and they did so through peaceful protests and hunger strikes.

Upon seeing the state of Madru Ramesh’s corpse, his elder brother Mandru Parishuddha Rao suffered from a heart attack and died. Shortly after this, the doctor who was performing the post mortem procedures, being a fellow Dalit, could not digest the brutality of the murders and the state of the corpses, so he returned home and ended up taking his own life by hanging himself. The Dalits then returned to Tsundur to fight back and demand justice, and they did so through peaceful protests and hunger strikes.

In one such hunger strike, a few weeks after the massacre, the same police force that had its ‘hands tied’ till then started an open-fire at the scene, insinuating that there were Naxalites present in the group. In the firing, they shot dead a young Dalit boy named Kommerla Anil Kumar, who was one of the very few people who had not only witnessed the killings with his own eyes but was also politically conscious, brilliantly articulate and able to present the real picture of what had happened on that day. He would’ve proven to be a strong witness in the courts and outside, had he been alive. This clearly showed where the allegiance of the police lay and just how far they were willing to go.

The Dalits continued to lead a powerful movement against this injustice, as part of which they boldly buried the victims in the heart of the village as a reminder of the brutality and violence inflicted upon them for many generations to come, and renamed it ‘Rakta Kshetram’. Now a certain organisation called Dalita Mahasabha, established in the aftermath of the Karamchedu massacre, was at the forefront of the struggle, fighting for justice for Dalit people, organising and mobilising people towards the cause under the leadership of Dalit activist Katti Padma Rao. Dalita Mahasabha called for a ‘Chalo Dilli’ program to escalate their demands for justice, and when they has reached Delhi, one of the Dalit women protesters Guduru Leyamma was killed in a hit and run accident there. All these put together brings the death count of the Tsunduru massacre to 12.

The Aftermath

The incident caused widespread outrage and protests were organised across the state of Andhra Pradesh. Several rights activists, intellectuals and other allies joined hands with the Dalita Mahasabha to demand a special court to be set up in the Tsundur to try the crimes. Meanwhile, the perpetrators neither acknowledged their crimes nor showed any signs of remorse. Instead, they openly defended the carnage and eventually formed an organisation called Sarvajana Abhyudaya Porata Samiti (society for the betterment of all people) under whose banner they proceeded to call for strikes, bandhs, rasta rokos etc in protest against the self-assertion of Dalit people.

They openly took to casteist slogans like ‘long live unity of forward castes’, ‘we will hang Katti Padma Rao’, ‘those who beg for every morsel should not be arrogant’ and so on, so for a long time the battle was fought not just in the courts but also in the streets. This was the first time after independence that the nation witnessed such a large-scale mobilisation of forward castes explicitly in the name of caste, and being referred to as ‘warriors for justice’ by the media and intelligentsia.

Unfortunately, this is a phenomenon that we continue to see today, where forward caste groups mobilise and agitate against the already disadvantaged backward caste groups and this is often met with accolades by the press, media and academia, since these fields are mostly full of Brahmins and other forward castes. The government, however, gave in to the pressure of the Dalit groups and met their demands to constitute a Special Court in Guntur in 1993. Human Rights activist B. Chandrasekhar was appointment as the public prosecutor in August 2000.

After numerous delays, allegations and objections raised by the accused to a range of issues including but not restricted to the legitimacy of the victims’ Dalit status, potential for bias towards Dalits by the appointed Dalit judge, death of 33 accused, relocation of the court to Tsundur and other such occurrences, the Special Court finally delivered its judgement in July 2007, convicting 21 people of murder and sentencing them to life imprisonment, and 35 others to a one-year imprisonment for committing the offences of voluntarily causing hurt by dangerous weapons, rioting with armed weapons or causing disappearance of evidence.

the perpetrators neither acknowledged their crimes nor showed any signs of remorse.

The rest of the accused, 123 in all, were acquitted. If the brutality and the scale of this massacre were to be really considered, this verdict seemed almost unacceptable. Hence the victims and the government filed criminal appeals and revision petitions at the High Court. The convicted also approached the High Court for acquittal, and out of all the appeals, in this case, the High Court chose to heed the ones convicted. Justice L. Narasimha Reddy and Justice M. S. K. Jaiswal constituted the High Court bench, and Bojja Tarakam (the iconic Mala-born human rights warrior who carried the weight of the three infamous Dalit massacres in Andhra Pradesh – Karamchedu, Tsunduru and Lakshmipeta. He also argued the case pertaining to Rohith Vemula’s social boycott at the University of Hyderabad) and V. Raghunath were the Special Public Prosecutors.

One Mr. Jaladi Moses filed an affidavit asking for the case to be transferred to another bench since they had lost faith in this bench. The court described Mr Moses as a person ‘said to be associated with an organisation and who did not figure as a witness in the case’, however, it is to be noted that Mr. Moses was the son of one of the victims and the nephew of another so it could safely be assumed that this lack of faith is not misplaced, considering the bench consisted of a Reddy person.

After what seemed like an almost pre-planned trial, the bench gave out the verdict that went by the technicalities of the case – like the FIR not being filed immediately by the Dalits (which clearly is a manifestation of the trust that the Dalits placed on the local police around the time of the massacre), witnesses’ inconsistent accounts of the timings of the events that occurred on the day of the massacre, the exact names of the attackers, and many more. The more fundamental issues, like the overall social context in which this incident had taken place, the obvious allegiance of the Tsunduru police to the feudal caste groups, Moses’ affidavit, the fact that these were not disparate, random murders but were well-planned, contempt-filled mass murders devised to make a point to the Dalits and subjugate them, along with several such underlying factors did not seem to be worthy of consideration to the eyes of the High Court bench.

The final verdict given by this bench was to overturn the convictions made by the Special Court at Tsunduru which would effectively set the accused free, indirectly implying that though 8 Dalits were murdered brutally in a caste-motivated large-scale attack, they were killed by nobody. Moreover, the bench had appealed to both parties, the Dalits and the feudal castes that amends need to be made from both sides and that “Carrying the old legacy would not be in the interest of anyone.” Such a simplistic verdict, completely devoid of India’s social context, built on the gross violation of Dalit peoples’ rights and their denial of justice is dangerous to say the least. Much has been written about the extent and manner in which the judicial system had failed Dalit victims time and again with its inherent upper caste bias.

This verdict led to an outrage among Dalit groups as was expected. The Dalita Mahasabha started pressurising the state government to take actions towards delivering justice to the Tsunduru victims, so the Andhra Pradesh Government has filed a Special Leave Petition (SLP) in Supreme Court challenging the High Court’s verdict of acquitting the 56 accused in the case.

The apex court stayed all further proceedings in the cases related to the Tsundur massacre, including the appeals by the accused before the High Court and the cases by the family members of the victims challenging the judgement of the special court in acquitting certain accused from the cases and also challenging the insufficient punishment issued by the special court.

Also read: The Dharmapuri Caste Violence of 2012 | #DalitHistoryMonth

The stay order was met with much rejoicing and celebration by the Tsunduru residents and the Dalita Mahasabha. However, it’s been close to 28 years and we are yet to witness the day when the Reddy and Kapu killers of Tsunduru are truly brought to justice by the courts of the nation.

References

1. Andhra Pradesh Civil Liberties Committee Report

2. Human Rights Forum

3. Round Table India (by Karthik Navayan)

4. Round Table India (by Dalit Camera: Through Un-Touchable Eyes)

5. India Together

6. Frontline

7. Youtube

Ravali is a Telugu Christian Dalit woman working in the eccentric development sector world of Bangalore. She is constantly trying to learn more about the cultures and languages of the 5 South Indian states. She loves gardening, chai, deadlifts, and well-written comedy shows. She is originally from Hyderabad and continues to believe that Biryani is the greatest food on the planet.

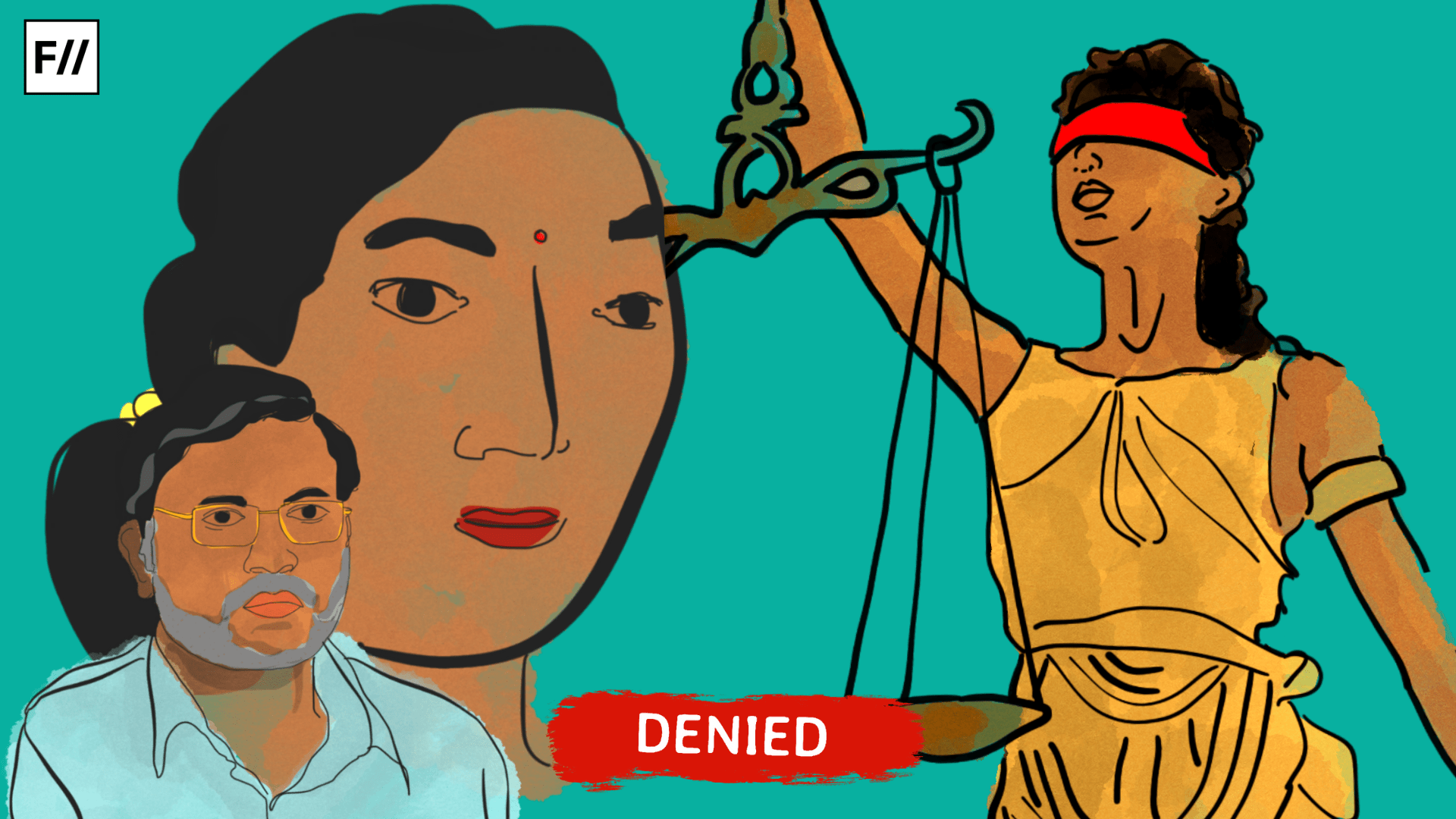

Featured Image: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism in India