Posted by Diya Narag

Anand Patwardhan is an Indian documentary filmmaker who targets crucial socio-political issues, that plague the country, in contemporary times. His style can be classified as bold, raw and most often, hard-hitting. He is both the interviewer and director, in all the films, interviewing different subjects, some random, some directly affected by the issue highlighted, making his films grounded in reality.

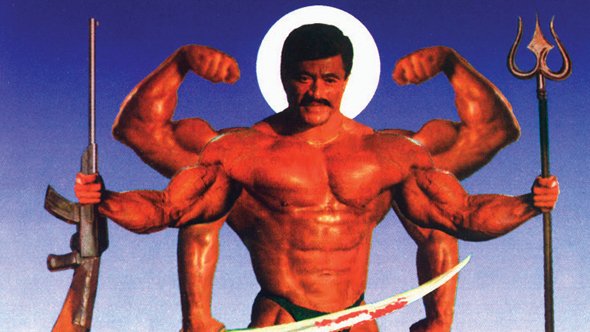

What makes his work distinctive is the authenticity that is brought forth with each documentary. The stark naked truth, which even if you believe you are aware of, hits you square in the face as you progressively navigate the film. His work is filled with local protest songs, and each documentary is uniquely accompanied with carefully picked songs by powerful personalities like Namdeo Dhasal, Vilas Ghoghre and so on. The selection of powerful sermons, hate speeches by the Shiv Sena or Vishwa Hindu Parishad, the slogans, pictures of idols and posters, add a powerful quality to the narrative which creates an impactful audio-visual experience for the viewer.

The documentary Father Son and Holy War (1994) chronicles the journey after the Babri Masjid demolition and the impact it had on citizens. It is divided into two parts – the idea of communal violence, and masculinity and machismo and how they are inherently related. A man’s insecurities are misdirected and are taken out on other genders or other communities.

During the riots, residential areas are set on fire, particularly the one in Malad which belonged to the Muslim community. A woman shares a horrific plight of her husband being beaten to death by 30 Hindu men, and her story of sexual assault where even the police refused to help her out. One witnesses the idea of women’s bodies being treated as territories to be conquered, very similar to what took place during the Partition with regard to the idea of conquering the ‘other’ community’s zan and zamin (land and women). Women’s bodies are seen as a site of respect and honour, and disrobing them meant disrobing the entire community’s honour.

An interesting linkage is made between religious fundamentalism and patriarchy, which can be seen through hate speeches

An interesting linkage is made between religious fundamentalism and patriarchy, which can be seen through hate speeches and making the other religion in question, seem weaker, and its male members, ‘less masculine’. This can be seen by targetting Muslim circumcision which affects their virility, their ‘apparent’ core strength and hence makes them more ‘effeminate’, in various hate speeches by the Shiv Sena in the documentary.

Hinduism is highlighted through the worshipping of polytheist Hindus, where goddesses are subsidiary allies and are paired to support gods like Ram through all their trials. During the celebrations of Shiv Jayanti Utsav, celebrating Chatrapati Shivaji’s life, in Maharasthra, many subjects talk about how Shivaji fought many battles against Muslims like the ‘Battle of Chakan’ and ‘The Battle of Pratapgarh’. Therefore they proclaim all Muslims as their enemy. We know through research today that Shivaji was never particularly anti-Muslim, and hired men from various religions in positions of power, in his army. This proves the fact that the warrior classes are historically idolised and through their likes and dislikes, however factually incorrect, stereotypes are perpetuated.

Also read: Sita’s Family: A Documentary On Public And Private Struggles For Independence

Statues of women bathing are installed at various places during the event, and when asked about them an interviewer speaks about the fact that during Shivaji’s rule, women and children could bathe freely, without the fear of assault, and hence the statues commemorate that era. The purpose of the statues is completely subverted as they becomes a site of oggling, passing lewd comments and implying that a woman is a ‘damsel’ in distress that needs to saved.

Cultural rituals like Sati are justified by various Hindu subjects, interviewed during the course of the documentary vociferously and are compared to attaining the status of a ‘goddess’, once they go through the ritual. A man talks about his own sister who went through the process and expresses his pride in her ‘brave’ martydom, stating she has now acquired the respect of a goddess. Other interviewees stated that anti-sati campaigns, were a conspiracy or mere manipulation by foreigners who wanted to advocate their religion and convert Hindus (Proselytism) into other religions. Any woman who opposed the idea of sati according to them, has loose morals or ‘virtues’.

A closer inspection is also made to into the culture of Bollywood films of that era, where the portrayal of female characters is hypersexualised, as objectified individuals, overshadowed by the ‘strong, masculine’ prototype of the perfect man. At the same time, an obsession with virility is observed on the streets, where locals sell different ‘Indian Herbs’ for the same purpose. A man comments on the fact that rape scenes in movies are enjoyable to watch, but will be even more enjoyable to do in real life, and a real man doesn’t just watch but also showcases his ability through actions. This comment gives us a key insight into the toxic masculinity portrayed through movies in the 1990s, where rape is romanticised by the Indian male audiences.

A closer inspection is also made to into the culture of Bollywood films of that era, where the portrayal of female characters are hypersexualised and are overshadowed by the ‘strong, masculine’ heroes.

Triple Talaq is also brought to light by Muslim women, who’ve been divorced and share their experiences of alienation, isolation and disrespect until some of them formed a platform called the ‘Lawyers Collective’ to help each other out. A Muslim woman speaks about the idea that Sati, Triple Talaq and other regressive rituals shouldn’t be separated but should be seen as a continuum in the same paradigm of oppression. Hence an intricate web is formed where religious rituals and culture often find twisted mechanims to subjugate a woman, relegate her to the lowest position in the social hierarchy and find ways to justify it.

The documentaries are insightful and give one a holistic perspective on various issues described, as we have subjects from all social stratas of society being interviewed. They’re also riddled with illogical superstitions, strange rationales and blind beliefs, that help individuals rationalize dominating religious minorities , especially women.

Also read: ‘Naseem’ Film Review: An Age That Had Passed

The documentary hints at a glimmer of hope as amongst the poor, there is less differentiation between the religious communities. It is shown in a kachha-residential area of Bombay, where both Hindus and Muslims, men and women, rebuild a Muslim dominated area which was burnt down. This clearly showcases that differences aren’t always intractable and they’re often not as stark as we make them out to be. His films can be interpreted in various ways, but the most important idea behind them is the director’s own expression of dismay and disappointment with a status-quoist system, unwilling to change. One needs to learn and unlearn things, understand gendering and socialisation of identities, analyse the concepts of power and powerlessness and most importantly start conversations to question the very system. A system where gender, caste, class and religion work in collusion to promote hierarchy, insecurity and ostracisation.

Diya Narag is a second-year political science student who likes exploring the world today through her writing. She is passionate about reading, writing poetry, and an ardent advocate of human rights issues, particularly concerning women, children and the marginalised. You can follow her on Facebook.

Featured Image Source: Film Southasia

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.