My first time was in a famous restaurant in New Delhi, when I was only twelve years old. I was skittish, yet excited. I knew it was time, and I knew I had found the right person to do it with. My friend told me she had tried it and she just wanted to keep going back. She was afraid I wouldn’t be able to stop either but, to be honest, I didn’t care. I didn’t care who saw us, I didn’t care how I looked, or how messy I got. My first time was as good as I expected it to be. When I was done, I moaned in satisfaction and wiped the sweat off my forehead with the back of my hand.

It was the best butter chicken I had ever had!

My friend was right; I would want to keep going back. I couldn’t get enough. Soon reality hit, and as I grew older, my body disobeyed the rather rigid beauty standards, making the very first love of my life come with a series of conditions applied.

If I have butter chicken for lunch, I promise to skip dinner.

If I have butter chicken with rice, I promise to work out for at least forty mins.

If I have butter chicken today, I promise to begin my diet tomorrow.

The mundane joy of eating food, the recognition of being lucky enough to have food to eat, was replaced with pangs of guilt, with every bite I took. There was no more a blithe disregard for the etiquette of eating, allowing myself to moan in satisfaction. All that was left was hate for my body.

Soon reality hit, and as I grew older, my body disobeyed the rather rigid beauty standards, making the very first love of my life come with a series of conditions applied.

Food has become so ubiquitously associated with body size, and in turn, body size with health. For example, a larger woman is assumed to be eating more, and her size is seen as a sign of an unhealthy body. We have come to associate happiness and health with thinness, ignoring the fraught and destructive narrative such associations create.

Jessica Valenti once said, as a thick woman, you are supposed to almost perform a public penance while eating. A performance of eating less, to let people believe that you, in fact, are committed to shrinking your body, and in turn, achieving longevity and happiness. This performance of eating with respect to your size is to behave.

This is what Erving Goffman calls the performance of self in everyday life. He used the term “performance” to refer to a set of practices that an individual does, to give meaning to themselves, to others and to the situation in hand. It becomes a form of communicating information about oneself to others and confirming one’s own identity. Performance encompasses the social practices that are part of Pierre Bourdieu’ concept of habitus. To perform in this sense, is to behave appropriately.

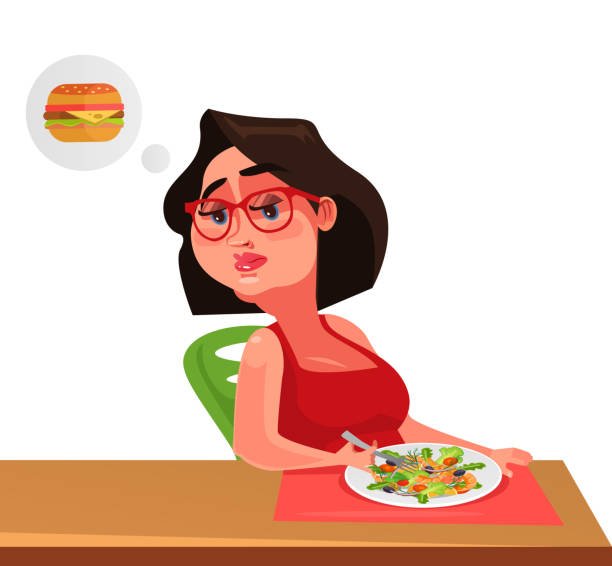

I performed skinny in front of my mother, as I would push the plate away after a couple of bites. “I am so full“, I would claim. I began to perform in front of male friends by ordering a salad or a grilled chicken—carefully selected dishes that would convince my audience that my body was going to change. I was making my body change, I was making my body shrink and they didn’t need to worry.

This form of performative eating is not only restricted to “thick” women. To explain the concept further, think about a time when you sat at a table with men and gulped down a beer and burger, not because you liked it (or maybe you did), but did not want to restrict yourself into the stereotype of women eating salads. Women are always forced to perform with food. Yet today, I choose to talk about thick women.

There was no more a blithe disregard for the etiquette of eating, allowing myself to moan in satisfaction. All that was left was hate for my body.

We have created a culture around us, in which performances of unhealthy eating are promoted and invisibilized in thicker bodies. Starvation, skipping meals and portion controls are all promoted and appraised behaviors, rather than signs of concern for the health of the person. This invisibilization is further heightened in India when women reach a “marriageable age” where losing weight is seen as integral to finding a good husband and being a fit wife.

This creates numerous dire consequences for thicker women. The American Psychological Association recently published a study which talked about the delayed diagnosis of eating disorders like Anorexia Nervosa, in bigger women. This is due to the fact that significant weight loss in people who are considered overweight is often rewarded, rather than being detected as a problem.

Also read: Nike’s New Plus Size Mannequin Says You Can Be Fat and Fit

We are promoting a toxic diet culture carefully concealed under the narrative of “health concerns.” We are ignoring the fallacies in the concept of equating health to body size. Let me give you an example. Often if you reiterate my argument to anyone you know, a common response will be “But you have to know about their, BMI, it’s unhealthy to have a high BMI!”

Harvard Health recently published an article debating the usefulness of the BMI or Body Mass Index. A higher BMI is linked with the risk of developing conditions like diabetes, arthritis, liver disease and so on. This is probably where your aunt is coming from when she gently tells you about how beautiful you are, and losing weight is more of a healthy sign.

I began to perform in front of male friends by ordering a salad or a grilled chicken—carefully selected dishes that would convince my audience that my body was going to change.

However, BMI is simply a measure of your size. Harvard Publishing reported that plenty of people have higher or lower BMI and are healthy while conversely plenty of folks with a normal BMI are unhealthy. Another study conducted reported that people with higher BMI tend to even live longer than those with a normal BMI. Another study reported that BMI is an inaccurate measure of cardiovascular health.

Also read: Eating Disorders Are Mental Illnesses, Not Physical Ones

What I am trying to prove here, is a simple point. We need to stop equating body size with health and in turn with beauty. We need to stop stigmatizing certain bodies. We need to stop making these bodies shrink and appease the male gaze. We need to stop creating a culture where women have to perform their relationship with food, instead of women eating out loud and moaning.

Featured Image Source: YouTube

About the author(s)

Undergraduate studying Religion and Gender, activist, feminist. Gender pronouns - she/her/hers

It is true that the BMI is overrated and that there are lots of people with a BMI to high or to low who are absolutely healthy. However, for the broad average the BMI is ONE helpful indicator to check ones health. Many times it was stated that the BMI should never be the only value for orientation. And for sure there are people who have perfect BMI but live an unhealthy life. In short: The BMI helps but is not the single health indicator.