The British Colonial power ruled over India for 190 years, from 1757 to 1947. In this period, fundamental administrative and legal changes were brought about—such as taking over the taxation system, establishment of courts, development of religion specific personal laws and application of common law principles derived from English Law in India.

Within the socio-legal ambit, the implication of usage of these principles meant that attitudes, perceptions, norms and beliefs, foreign to the sub-continent were being imposed and reinforced, through such colonial laws and the idea of morality constructed by them. Be it now repealed Section 497—Adultery, Section 377—which implied criminalisation of homosexuality, or laws on Marital Rape, there has been a colonial colour to the laws related to women and the LGBTQ+ community in India. In this article, I intend to uncover the influence of colonial misogyny on present day attitudes and ideas of morality analysing these laws.

The Two-Fold Action

The sexism brought about by the colonial laws and principles, combined with the pre-existing patriarchal norms of Indian society, led to a two-layered net of the misogynistic framework that govern the lives and legal identities of women and queer persons.

This two-fold action resulted in creating greater discriminatory mechanisms with the usage of the colonial laws which culturally were foreign to Indian society. The consequence thus, led to experience of greater marginalisation and discrimination by queer persons and women, than they would have experienced in a traditional patriarchal set-up native to the Indian subcontinent.

The sexism brought about by the colonial laws and principles, combined with the pre-existing patriarchal norms of Indian society, led to a two-layered net of the misogynistic framework that govern the lives and legal identities of women and queer persons.

Change in the notion of morality

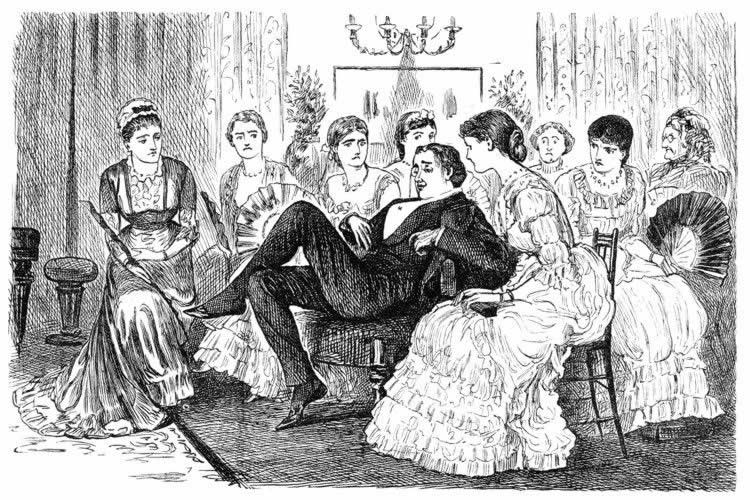

The laws and policies imposed by the British in India changed the notion of morality and ‘righteous behaviour’, that was created through the lens of a Victorian conservative society. Although the British helped abolish female specific social evils such as ‘Sati’, with Indian reformers like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, their own idea of women in society was at best orthodox and misogynist.

The ideal woman in the Victorian era was to be at home, domestically inclined and ‘kept away’ from public spheres. The concept of “Pater Familias”—the patriarchal hierarchy within a family where the man is seen as the head of the family and the woman inferior to him, was preached in the society. This distinction is visible in one of the most popular poems of the era called, “The Angel in the House” by Coverntry Patmore, written in 1854, it reads:

“Man must be pleased; but him to please

Is woman’s pleasure; down the gulf

Of his condoled necessities

She casts her best, she flings herself …”

Imported victorian laws that show sexism

1. Marital Rape

Marital Rape is intercourse by a man with his wife without consent, obtained by force, threat of force, or physical violence, or when she is unable to give consent. Marital rape could be by the use of force only, a battering rape or a sadistic/obsessive rape. It is a non-consensual act of violent perversion by a husband against the wife where she is physically and sexually abused.

The present reluctance to not acknowledging marital rape can be traced back to statements by Sir Mathew Hale, Chief Justice in England, during the 1600s. He wrote,

“The husband cannot be guilty of a rape committed by himself upon his lawful wife, for by their mutual matrimonial consent and contract, the wife hath given herself in kind unto the husband, whom she cannot retract.”

Not surprisingly, married women were never the subject of rape laws. Laws bestowed an absolute immunity on the husband in respect to his wife, solely on the basis of the marital relation. This exception was thus not created in the criminal laws applied in India during the British rule, and still continue to find no place in the IPC today.

In Section 375, provision of rape in the Indian Penal Code (IPC) in extremely archaic sentiments, is defined in its exception clause as,

“Sexual intercourse by man with his own wife, the wife not being under 15 years of age, is not rape.”

In Section 376 the IPC defines the punishment for the crime of rape:

“The rapist should be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which shall not be less than 7 years but which may extend to life or for a term extending up to 10 years and shall also be liable to fine unless the woman raped is his own wife, and is not under 12 years of age, in which case, he shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to 2 years with fine or with both.”

The conservative view of women as property is shown in now repealed Section 497 of the IPC law against Adultery, which earlier deemed women to be property of their husbands with lack of autonomy and legal character.

2. Adultery (now repealed) Section 497

In September,2018 the Supreme Court of India stuck down a 158-year-old colonial-era law which treated women as the “property” of men.

Section 497 provided,

“Whoever has sexual intercourse with a person who is and whom he knows or has reason to believe to be the wife of another man, without the consent or connivance of that man, such sexual intercourse not amounting to the offence of rape, is guilty of the offence of adultery.”

The implication of this law being that women lacked legal autonomy and could not file a complaint against an adulterous husband and the woman could not be punished as an abettor because she was not considered an individual legal entity.

Within the socio-legal ambit, the implication of usage of these principles meant that attitudes, perceptions, norms and beliefs, foreign to the sub-continent were being imposed and reinforced, through laws and the idea of morality constructed by them.

3. Section 377 of the IPC

After a long and resilient effort by the LGBTQ+ community and their allies, on September 6, 2018, Section 377 (which criminalises “unnatural sexual activity”) was repealed.

However, on examination the roots of this homophobic law, it shows to have been a legacy of the colonial rule in India.

The clause of Section 377, criminalising Homosexuality was introduced as an anti-sodomy law in India by the British. The Sexual Offences Act of 1967 decriminalised the acts of homosexuality and sodomy between two consenting adults in England, but Section 377 of the IPC remained.

Section 377 defined “unnatural” offences:

“Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal shall be punished with imprisonment for life, or with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to ten years, and shall also be liable to fine.”

The clause was based on traditional Judeo-Christian moral and ethical standards. The perception of sex was purely for reproductive functionality. It defined any non-procreative sexual activity is viewed as being “against the order of nature”.

Also read: Let’s Talk About The Long Overdue Reforms Needed In The Abortion Laws Of India

However, India’s Pre-Colonial idea of homosexuality was rather accepting, evident through the art, literature, religious texts, sculpture and folklore. In scholars Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai’s groundbreaking essay collection on same-sex love in India, Hindus embraced a range of ideas on gender and sexuality as far back as the Vedic period, around 4000 B.C.

Hinduism’s sacred texts tell tales of same-sex love and gender fluid figures. The Hindu deities such as Shiva is worshipped as a multi-gendered person in what’s known as his Ardhanarishvara form. Hindu texts refer to a “third gender” and in popular vernacular are referred to as “Hijras”, who are known to play a social and religious function in everyday life. In the Kama Sutra, one of the most celebrated literature on sex and sexuality, there is reference to ‘Svairini’ who is said to be a liberated woman who cohabitates with another woman.

Also read: 2 Subversive Pre-Colonial Texts In Indian Fiction We Should Know About

Opportunity through Distinct Legacies

To me, modern India is the product of different histories, ideologies, beliefs and cultures; some harmonious and some conflicting. However, this creates a great opportunity for every generation to adopt and hone what brings peace and equality to society and to reject and abort what brings pain and prejudice to society, such could be the legacy of modern India.

Aryika is a law student and an intersectional feminist. She is passionate about food, fashion and feminism. She would like to help make the law more inclusive. You can follow her on Facebook.

Featured Image Source: Spiked

Very well expressed nd written ??