The Channar revolt, Channar Lahala or Mura Murakkal Saharam took place in the early 1800s in Travancore, modern day Kerala. I say the 1800s because it was not one day. It was a rebellion that grew out of everyday repression.

Our society is no stranger to clothing being used as a tool of repression, especially for women. There are always people judging you for how you dress. But imagine someone tearing off the top clothes of a woman in front of your eyes and nobody doing anything about it. Indian history is not unknown to such examples. Kerala, which today is seen as a standard in itself for progress in spheres like literacy and self-sufficiency, has been witness to a horrific account of cruelty, basing itself on women’s’ breasts.

The Channar Revolt

In nineteenth-century Travancore, it was a socially acceptable norm for women to be seen naked from waist up in public places. Higher caste women like the Nairs (Savarna) were expected to bare their upper bodies only in temples in front of priests, who were considered an authority of god.

But lower caste women (Avarna), the toddy tapping Shanars or Nadars being an example, were not allowed to wear a cloth over their breasts in public. As a matter of fact, baring your breasts in front of members of the higher caste was seen as a display of respect. If any woman disagreed with the practise, they were obliged to pay a ‘breast tax’ or Mula Karam whose amount was determined, quite sickeningly, by the size of their breasts.

It was the women of the Nadar community who initiated a change against it. They declared they wanted to have the right to dress however they want. They did get the right to be dressed as per their convenience, but partly. In 1813, perhaps to contain the inevitable chaos and to please the upper classes at the same time, the Dewan (judicial officer) of the Travancore court, Colonel John Munro took a step.

He decreed that Nadar women could cover their breasts only if they had converted to Christianity first, and then they could only wear long blouses similar to Muslims or Syrian Christians of the time. Nadar women were forbidden to wear the Nair sharf and instead were allowed to wear the Kuppayam, a type of jacket worn by Syrian Christians, Shonagas, and Mappilas.

Soon after, the order was not expanded in scope, but withdrawn. The Pindakars were members of the king’s council who argued that this move would end the difference that identified with their castes.

As a matter of fact, baring your breasts in front of members of the higher caste was seen as a display of respect. If any woman disagreed with the practise, they were obliged to pay a “breast tax” or Mula Karam whose amount was determined, quite sickeningly, by the size of their breasts.

But it wasn’t enough for the rebellious women of the Nadar community; it was not just a matter of modesty but had become a symbol of equal rights. They questioned as to why they could not be dressed like the Hindu women, being Hindu themselves. The reaction to this was that the Nairs soon took to tearing these women’s clothes apart in public. Complaints were also filed in courts against this dress change, especially because the Nadars were also refusing to render free labour for the upper castes.

In 1829, the government of Travancore ordered these women to refrain from covering their upper bodies, but the revolt had already begun.

What came to be known as Channar Lahala left images of people stripping the women of their upper clothes and houses being burned down. This turned more heated as slavery was abolished in Travancore in 1855, and the upper caste felt like they were losing control. The Raja proclaimed again in 1859 that Nadar women will not be allowed to dress like their Savarana counterparts. This was perhaps one of the first fights against female oppression in Kerala. “This issue went on well into the 20th century,” explains Dr K Gopalankutty, president of the South Indian History Congress. “Clothing is a marker of one’s social identity, and the blouse took on a symbolic role.”

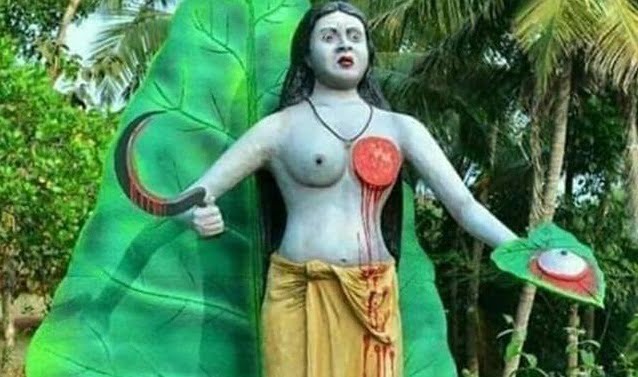

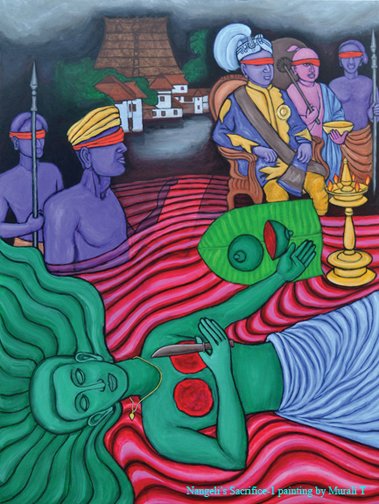

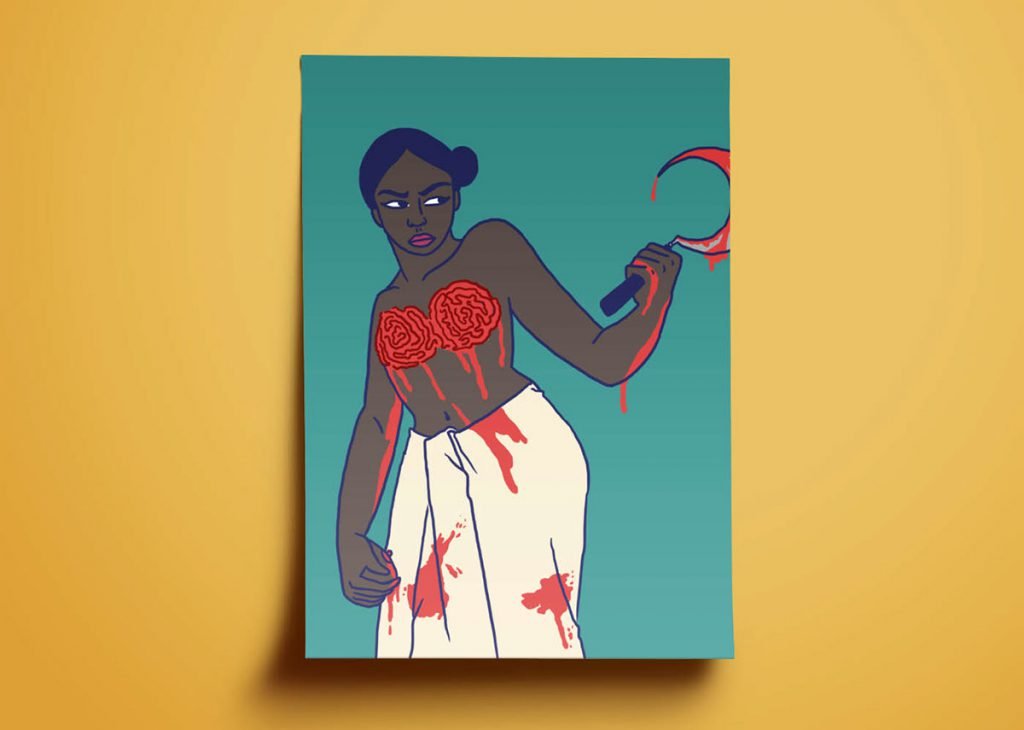

Nangeli

Among the many stories of the rebellious women of Travancore, ignored by historians fed by wealthy lords, is the story of Nangeli. She is said to have been a poor woman during those times, who was asked for breast tax. Enraged at the idea that the dimensions of her breasts would determine how much she would pay, she cut off her breasts and handed them to the officials. She bled to death on the spot. Her husband upon finding out was so scared and distraught that he jumped in her funeral pyre. This has been dubbed by historians as the first example they have come across of male Sati.

The place she fell has been named “Mulachiparambu” or the breast woman’s plot, dismissively so. Nangeli may not have meant much to the administration of the time, but her memory means a lot in our day.

Also read: Kerala’s Casteist Breast Tax And The Story Of Nangeli

Modern vandalism of history

But certain members of the society seem to think otherwise. In 2016, after various oppositions, the CBSE (Central Board of Secondary Education) decided to delete a section about the Channar revolt from its NCERT books, that were being used in around 19000 schools. “The book coordinator Professor Kiran Devendra, however, denied any knowledge of opposition by student or parent alike to the contents of the textbook which she deemed factually correct,” wrote The Quint in 2016. The Madras High Court ruled that this was degrading the Indian society.

In 2016, after various oppositions, the CBSE (Central Board of Secondary Education) decided to delete a section about the Channar Revolt from its NCERT books, that were being used in around 19000 schools.

This perhaps accurately represents the voice of ignorance that rages with such vigour in our country. The fact that there is no historical evidence of the story and no written testimonies, is because people who inflict the oppression do not discuss it in textbooks. To quote Winston Churchill, “History is written by the victors.” Revolts like these take root in the violence that exists in not letting the oppressed tell their stories and not letting them be remembered.

The Channar revolt reminds us that the society continues to find ways to deepen the divisions among people. In order to retain their fortunes, in most cases, the wealthy populace invents ways that will keep the poor busy and won’t let them focus on improving their lives.

The idea of baring the bosoms comes from ancient times, when people of all genders in Travancore region wore sparse clothing to battle the heat of the region. It is very similar to modern men and women wearing shorts and tank tops in summer. The idea had spawned from common sense and not social norm.

But the way this practise was twisted into a tool to downsize the poor is very troubling. What is more unfair is how the practice that was natural to all humans, was narrowed down on women. It came onto them because they were poor, and they were women. This is a reminder how inequalities so commonly intersect in all spaces and times. So, we shall stop at nothing but equality, which will be achieved through mutiny and solidarity alike.

Also read: Why NCERT Dropping Chapters From History Textbooks Is A Feminist Concern

References

Featured Image: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism in India

About the author(s)

Avni is a student of Public Policy and a fresh writer. She aspires to understand what the world is doing and then do something of her own.

DO YOU KNOW THE REAL HISTORY OF VALANKAIKONDA NADAR KSHATHRIYA. NADAR MEANS ONE WHO RULES THE LAND. WITHOUT HAVING PROPER EVIDENCE. NOT SPREAD THIS KIND OF FABRICATED STORIES DEAR. IF YOU WANT KNOW THE GLORIOUS HISTORY OF NADAR PLEASE CONTACT US