“History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce.” – Karl Marx

The history of violence against minorities remain largely invisible in mainstream media. While breaking news don’t dwell on these crimes, they are relegated as feature pieces and somber reminders on the “crime’s” anniversary. Among the numerous such examples is the Keezhvenmani massacre.

Christmas day, this year marked the 51st anniversary of the Keezhvenmani massacre. The news media did their solemn recap of this targeted caste/class violence against 44 individuals (mostly children and women). In 1968, Keezhvenmani, (presently part of Nagapattinam) was part of the Thanjavur district, Tamil Nadu. Thanjavur, central in this tragedy and lays bare the contradictions between a feudalistic ground reality and the idealistic political rhetoric.

Huts without roof. Huts without walls. Huts ground to dust. To ash. Huts with broken bangle pieces. A silence that ill became a cheri (a Harijan street) accustomed to barking dogs, screeching children, gossiping women and drunken brawls.

– Haunted by fire (Mythili Sivaraman)

Raised fist carried as part of the 2014 inauguration of the Keezhvenmani martyrs memorial, Wikipedia

The tragedy has been usually described as wage dispute between Dalit landless laborers and the land-owning communities. This narrative is more than often used to describe the violent human rights abuses that resulted in the Keezhvenmani massacre. Mythili Sivaraman, who had chronicled the incident in her essays, Haunted by Fire describes in great depth the wider socio-economic consequences of the caste relations and land ownership patterns. She also analyses the failings of ‘green revolution’ that served to create more class inequalities along caste lines.

The Gentlemen Killers of Kilvenmani describes the wider societal inequalities prevalent in the rural rice bowl of Tamil Nadu, Thanjavur. Disproportionate land-ownership pattern, evident from the 1961 census coupled with an ineffective system for fair wages, a large number of landless Dalit labourers and caste oppressions were instrumental in creating the agrarian distress in Keezhvenmani.

The Incident

In Keezhvenmani, the planned attack by the landed gentry was against the rising tide of class-caste consciousness among the landless Dalit labourers. The agricultural belt has been infamous for caste violence and negligence of human rights.

The communists, active in the areas had organized many of the labourers into unions to demand fairer wages. In response to this, the landowners created their own union to curb demands by the labourers and bought in labour from other villages as and when needed. The Dalit labourers however, resisted the demands and refused work. This was seen as an insult, and following the months of escalating tensions (when many were threatened, thrashed, harassed and killed) on 25, December 1968, following gun-fire violence, 44 people were burned alive in Keezhvenmani.

Also read: Watch: How Has The Indian Government Failed Dalit Women?

The headlines next day described the deaths of 44 without taking into account the power relations of caste and class. The Hindu’s headline on December 27, 1968 read, “42 Persons burnt alive in Thanjavur Villlage following Kisan Clashes.” The Indian Express, “Kisan Feud Turns Violent, 42 burnt alive in Thanjavur” and Dinamani, “Clashes between Kisans- 42 burnt alive” (1968).

Human rights violations are not breaking news, in fact the 24-hour news cycle has numbed their impact, by large measures. This inclination has been marked in the articles pertaining to this issue.

Political rhetoric vs Reality

In 1967, newly elected DMK government was seen largely as an “anti-establishment party” against the Congress old-guard. Having gained majority on a populist platform, the ruling DMK had to cave in to the land-owning communities for the fulfilment of their election promise of 3 measures of rice for a rupee. The half-hearted outrage and the downplaying of the issue explains the ruling party’s indifference towards Dalit empowerment.

By imitating the caste bias, they accused their predecessors of, votes got codified along caste lines. Even though, CPI (DMKs election ally) played an active role in the struggles by the landless labourers, the apathy of the state machinery was evident, in the Madras High Court’s acquittal of the 25 accused, the following year.

The issue of land rights has always been a point of contention for the varied political ideologies in the state. While, there is widespread agreement that ‘land is empowerment’, very few follow through with their political reforms. More often electoral gains defined by caste dictates the party’s position with regard to caste/class oppression. This bias is seen in the case of this tragedy as well.

Relevance of Land Rights

Hugo Gorringo, a researcher on Dalit politics pertaining to Tamil Nadu, explains the significance of land rights. An excerpt from his book Land and Labour: Exclusion from Ownership:

‘The key issue’, as a Dalit activist noted, is land. This is the main demand’ (Ramesh, Interview, February 2015). ‘Land’, as Thangaraj (2003: 137) argues, ‘is closely associated with the caste system’ and land ownership maps onto social dominance. He notes how Scheduled Castes comprise 19.18 per cent of the population but control only 7.1 per cent of the land. As the leader of the Social Equality Front (Samuga Samuthuva Padai) put it: ‘Land politics is caste politics … land is caste and caste is land’ (Sivakami Speech, June 2012). The significance of land ownership is illustrated in the case of the Uthapuram conflict discussed above. Jeyaharan, an academic, pastor and activist in Madurai argued that the Pillaimar caste were unable to respond violently because the local Dalits own land. This means that they are not at mercy of landlords or needing to work every day (Personal Communication, February 2012).

Following the tragedy, Krishnammal and her husband Jeganathan, Gandhian social justice activists shifted to Keezhvenmani. Their organization, Land for Tillers Freedom (LAFTI) founded in 1981 has till date, she says, distributed 15,000 acres of land to 15,000 Dalit women.

“I was not doing charity. When a woman eats her meal at the end of the day, it is not my charity. It is her hard work. I just facilitated that hard work. But I’m grateful to god I was at least able to do that.”

Speaking about Keezhvenmani, she says,

“Now almost all dalit families there now own 2 to 3 acres of land. Most children belonging to these families have been educated and have found jobs in cities- in Mumbai, even in the Andamans. But if there’s one thing that disheartens me, it is the apathy of these very people who have suffered much injustice in the past. They have moved on, but they fail to see that many others have not. They think solely of their journey forward, breaking away from the shackles that once bound them. It doesn’t bother them that they are doing nothing to help those less privileged. The past seems forgotten.”

Also read: Did The Cheque Bounce For Dalit Women In The Interim Union Budget 2019?

Amnesia of popular culture

Keezhvenmani has been part of left and Dalit discourses but remain forgotten in many mainstream platforms. Kuruthipunal (River of Blood), by Indira Parthasarthy was one of the first novels about the massacre. While the factual description of the tragedy has been written by Mythili Sivaraman, Meena Kandswamy’s, The Gypsy Goddess is a narrative encompassing the various events in Keezhvenmani. It gives a fictionalised version of the events that transpired. Her version explicitly describes the harassment and struggles faced by women. The distinctive feminist angle portrayed in her work makes the novel a refreshing example of subaltern narrative.

The 1983, released film Kan Sivandhal, Man Sivakkum (The earth turns red, if the eye reddens) directed by Sreedhar Rajan depicts the struggle onscreen. Warring ideologies often leave the less-privileged at a disadvantage. The film describes the powers struggle and the subsequent measures adopted by those in power to curb any uprising.

While, there is widespread agreement that ‘land is empowerment’, very few follow through with their political reforms.

Ramiahvin Kudisai (Ramiah’s Hut 2005), is probably the only documentary based on the incident. The film weaves in interviews of Dalit eyewitnesses who lost their kin in the massacre, retired local police officers and even a Mirasdar who was initially convicted of the crime. While these accounts remain, popular memory seems to have faded away, with the anniversary being observed every year. The larger socio-economic and political issues that pervaded Keezhvenmani still remain as unresolved issues.

References

- Haunted by Fire: Essays on Caste, Class, Exploitation and Emancipation- Mythili Sivaraman

- The Din of Silence_ Reconstructing the Keezhvenmani Dalit Massacre

- Fifty Years of Keezhvenmani Massacre, in Literature and Film

- How the Dalit discourse is playing out in Tamil Nadu, 48 years after Keezhvenmani

- 50 Years Later, the Shadow of Keezhvenmani Continues to Hover Over our Republic – Countercurrents

- 50 years after the Keezhvenmani massacre, what has changed for Dalits in Tamil Nadu_- The New Indian Express

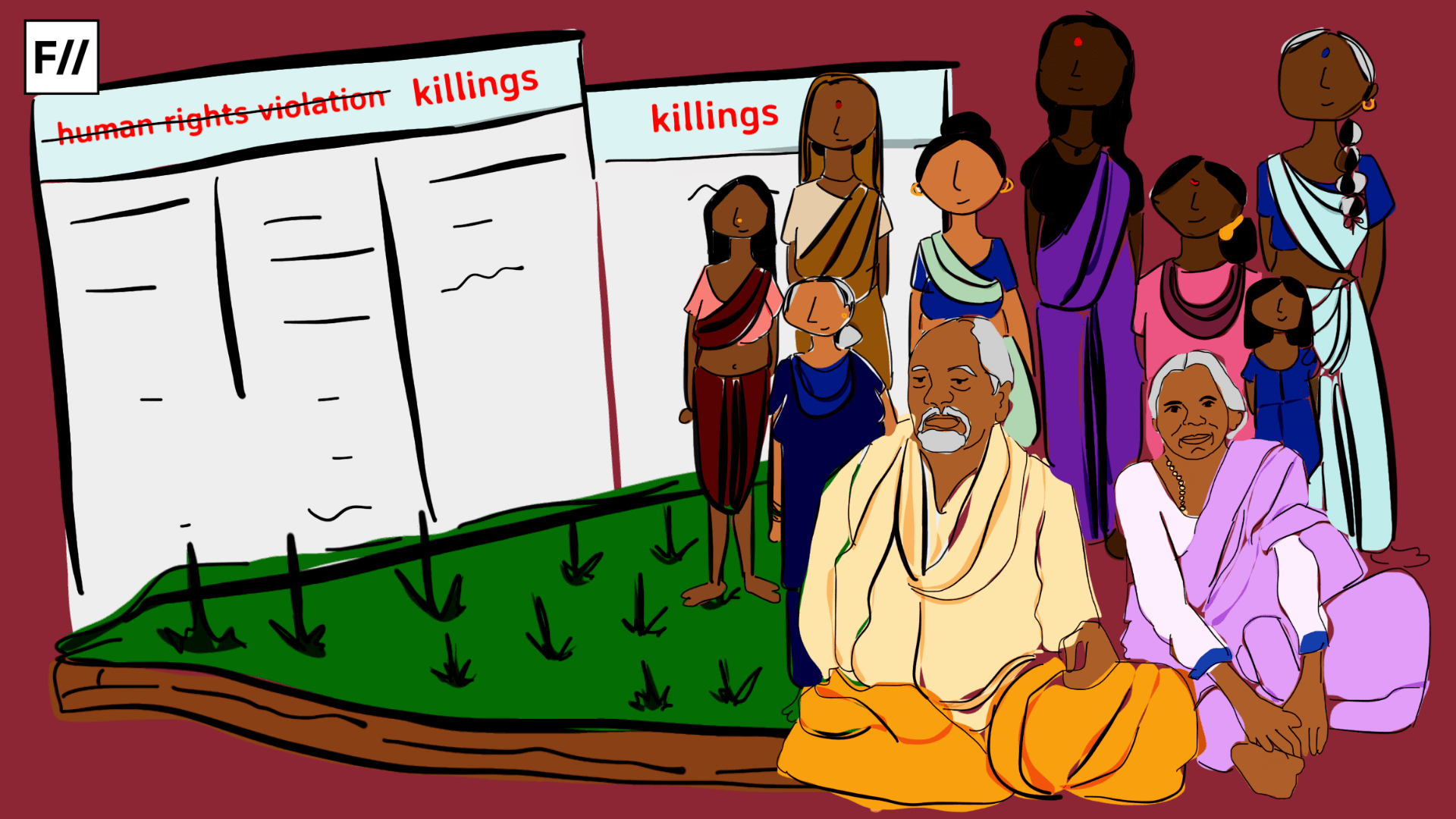

Featured Image: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism in India

About the author(s)

A homemaker trying to wedge feminism into daily life. Ambica enjoys reading and is a news junkie. She loves political satire, especially by female comedians. Her other interests are films and plays.