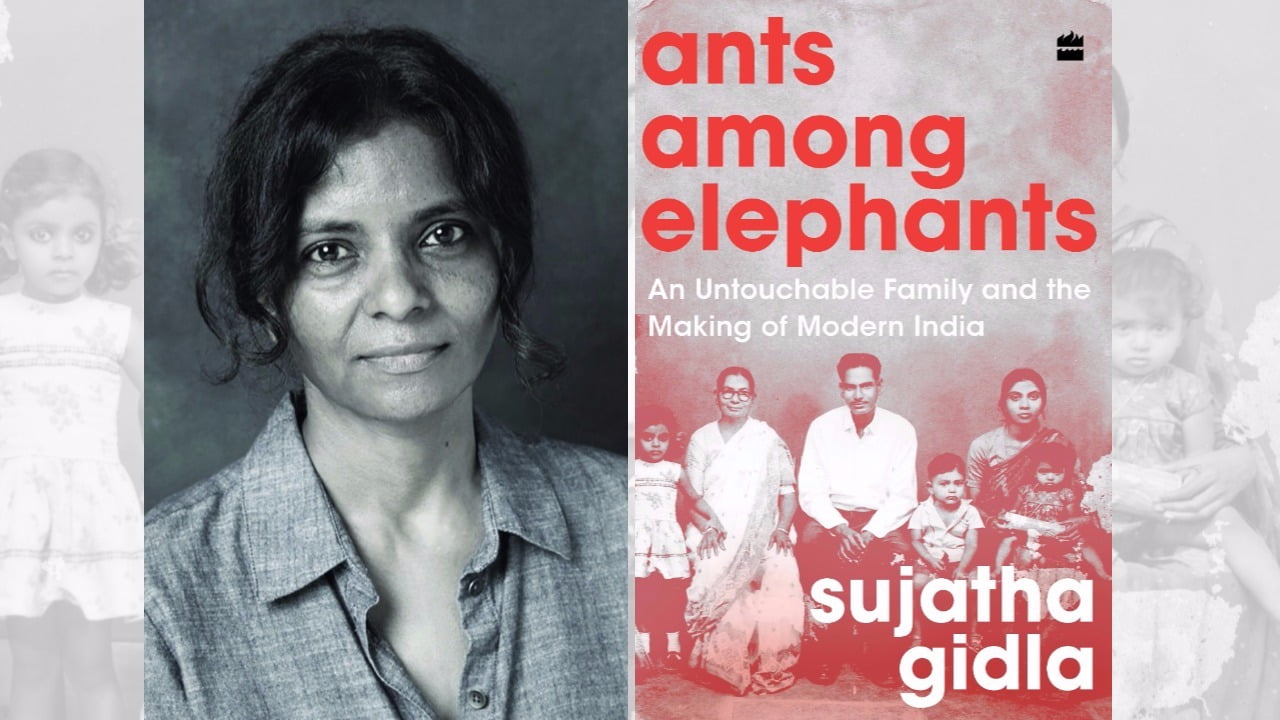

The book ‘Ants Among Elephants : An Untouchable Family and the Making of Modern India’ is a powerful semi autobiographical work of Sujatha Gidla as she traces the struggles of the ‘untouchables’ to assert her identity and agency amidst the turbulent times of nation building. It is an outstanding piece of work as it traces the complexities of what it means to be a Dalit and its heavily gendered existence.

Ants Among Elephants (2017)

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Genre: Non Fiction

Author: Sujatha Gidla

Ants Among Elephants demystifies the romanticism that we associate with the anti colonial movement in India and the subsequent efforts to decolonise a nation brimming with possibilities. What urged me to pick up the book was the void that had been created in the subaltern studies when it comes to reading the Dalit feminist experience. We have read extensively on the powerful interventions made by the marginalised in the political project of post independent India, but somehow somewhere the margin itself had been highly exclusionary; Gidla fills up the void and brings to forefront the urgency to differentiate within the Dalit experience itself: that of the untouchable man and the untouchable woman.

We have read extensively on the powerful interventions made by the marginalised in the political project of post independent India, but somehow somewhere the margin itself had been highly exclusionary; Gidla fills up the void and brings to forefront the urgency to differentiate within the Dalit experience itself: that of the untouchable man and the untouchable woman.

Ants Among Elephants was extensive and extremely engaging as it enabled me to place oppression and locate patriarchy in the most unthinkable of context and spaces. While at places it talks about possibilities of a powerful solidarity, yet in others it kindles in one, a sense of shame and retreat; retreating is important in an intersectional feminist project. It is important to know where to stop asserting epistemic experiential authority, learn and introspect rather than appropriate. Gidla through her Dalit language prevents such appropriation. Being from an upper class non-Dalit background, this reading had aroused multiple emotions in me and hit hard on my privileges while still humanising the female subjectivity and experience.

The book has graphic description of violence: symbolic violence. While reading the book I was being continually reminded what Ambedkar had said, that there is no caste but only castes in India. Castes no matter how the Gandhian Project had chosen to view it in the light of a ‘united India’, had only divided India further. Ambedkar had argued India’s reality is far from communal harmony and fraternity, and that castes in India are the sole reality. The reality that transforms itself into class, makes them hate each other instead of forging resistance against the oppressor, the reality that makes them ‘enclosed immobile classes’, the reality that nurtures multiple patriarchies, multiple untouchable bodies that find no language to fight Bramhinism. Gidla while leaving a Marxist imprint of the arousal of class consciousness, an armed struggle, drops the tempo to return to the caste ridden soils of India set in the Nehruvian project of development. Violence had been differently mapped by different interest groups to claim their authority in the political movements, but violence leashed out on and violence resorted to, by the Dalit female stands overarching throughout the book.

idla while leaving a Marxist imprint of the arousal of class consciousness, an armed struggle, drops the tempo to return to the caste ridden soils of India set in the Nehruvian project of development. Violence had been differently mapped by different interest groups to claim their authority in the political movements, but violence leashed out on and violence resorted to, by the Dalit female stands overarching throughout the book.

Gidla takes her readers through the perplexities that she faces while reflecting upon her identity, till at one point the readers themselves would be utterly disoriented. She realises that religion could be used variably but her caste identity would remain constant. Where in her village ‘caste is life, life is caste’ wealth, religion only underlines caste identity. She reflects how different the untouchable Christian had been from the Brahmin Christian. Where Christians had been tagged as foreign and impure by the majoritarian Hindus of the land, Gidla’s experience opens up the internalisation of the same exclusionary practice by the religious minorities in order to further differentiate themselves for material gains. Gidla and her family stands at the peak end of the exclusion where they have been continually pushed out and cornered throughout their efforts to make themselves upwardly mobile and had time and again faced exclusion from not only the ‘caste people’, but the various groups of untouchables also including their own.

In the course of understanding her identity in real and in Ants Among Elephants , she traces the journey of her uncle Satyam and her mother Manjula in particular and other relatives in general, both of whose experiences reveal why was that she was considered a ‘shit lilly’, in her university years whereas other Christian girls from different regions weren’t. It was through the history of struggle of her family that she opened up the untold histories of illegal subordination, pauperization and finally extermination of the powerless in the face of not only the colonial state but also the very anti-colonial nationalist project that stretches from the Congress to the Communists.

Gidla doesn’t merely talk about important recorded events that uncover the banality of nation building, but she sets them against the background of everyday caste violence that are nothing short of caste wars, lived and channelized through the Dalit person.

Gidla doesn’t merely talk about important recorded events that uncover the banality of nation building, but she sets them against the background of everyday caste violence that are nothing short of caste wars, lived and channelized through the Dalit person. Despite the best of efforts by the Kambhan family to which the author belonged, to challenge the disabilities placed on them on account of being untouchables, by availing western education and dressing up differently, upward mobility in terms of economic and cultural capital remained a myth. Caste discrimination remained in academic and political spaces. Caste consciousness was not only hard to develop but even in cases where it had it was extremely difficult to even maintain it.

Also read: Book Review: Woman At Point Zero By Nawal El Saadawi

But through Satyam’s account, the history of shared deprivation amongst the untouchables could find expression, and through the innumerable instances of resistance against state oppression, the Dalit voice in post independent India could be traced. The process though marked by failures reveals the relentless negotiations that the Dalit had to make; within the party he had faith in to restore an egalitarian society and the capitalist oppressive so called developmental state. Gidla stated the villagers of the untouchable colony had rightly observed on the eve of independence, that only the colour of the ruler’s skin had changed, from white to dark!

The author uses satire to catch the reader’s attention to absurdities associated with the whole identity called Dalit, a woman, but takes great care to point out the long drawn processes that had made those absurdities normal in her life and the life of her mother. Whereas casteism was normalised in the Communist party and the politics of the nation, in the ghettoisation of the untouchable, growing up in Elwin Peta’s filthy neighbourhood and in all dalit neighbourhood, Gidla situates the Dalit woman’s struggles differently. Where her uncle despite leading a painful life got recognition across the state for his contributions to politics, her mother along with other Dalit women fought and still fighting a battle that goes unrecorded unrecognised and ritualised under the norms of patriarchy.

It is at this juncture caste becomes gendered and gender becomes a qualifier of caste itself. It qualified when despite being way more educated, Manjula was subject to routine torture by her Dalit husband. It became a qualifier when Manjula started donning the modern saree in college and was harassed by the ‘caste men’, who never used to mete out such behaviour to the ‘caste women’. Caste consciousness amongst the Dalit female was starkly different as the Dalit woman lost sight of her immediate comrades and looked for emancipation in the casteist practices. The Dalit woman despite economically independent wasn’t free from the unequal division of labour and the drudgeries of housework. Gidla takes her readers through the location of agency and finds it nowhere, not even in the Dalit female body.

Also read: Book Review: Pyre By Perumal Murugan

Gidla’s narration floats through the bloody history of independence, Telengana struggle and the Naxalite movement. In all these movements she directs our attention to the atrocities meted out to the minorities. In the political projects of building solidarity, caste oppression had often been overlooked and so do gendered violence. Ants Among Elephants provides strong account of the voices that had been subdued in these historical projects and had reinstated those lost voices through the feminist lens. The ants are in fact the counter narrators and not just untouchables silently living caste and gender violence. The ants despite being trampled repeatedly had never failed to sting the elephants and history shall remember and shall be reminded of such resistance.

Featured Image Source: Firstpost

About the author(s)

I am a student of sociology and gender studies. I did my masters in sociology at Delhi School of Economics. However my interest in gender studies had intrigued me to take up this course seriously. Currently I am enrolled for masters at Ambedkar University Delhi. My interest areas lie in researching on the epistemology of protest, nationalism, queerness , the sociology of the family, student politics, work, body and labour. I aspire to write more and bring my insights closer to activism. Intersectional understanding for me had helped me become a better political individual.