Trust Bollywood to capitalise on misrepresentation! Many Bollywood movies play around with clichéd, stereotypical tropes like the funny Sikh man, the shrewd Gujarati businessman, the effeminate gay man, the nagging wife, the Muslim antagonist, etc. One of such communities which has been highly misrepresented time and again is that of the Hijras.

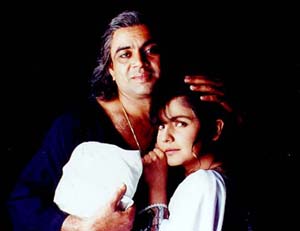

The picture is a screenshot taken from the movie, ‘Sadak’ (1991), directed by Mahesh Bhatt. The picture depicts the character of Maharani, a Hijra and a brothel-owner, portrayed by the legendary actor Late Sadashiv Amrapurkar. The movie presents Maharani as a cunning, evil and sadistic brothel-owner who acts as the main antagonist. The character of Maharani is hailed as one of the most terrifying villains of Bollywood, and Amrapurkar had won a Filmfare award for his portrayal of Maharani.

Throughout the movie, as seen in the picture as well, the portrayal of Maharani is terrifying. Amrapurkar adopts exaggerated expressions, amplified mannerisms and a peculiar form of intonation. These features act as signs which signify the cruelty of the character. This is the first level of signification. This primary signification and the fact that the character is a Hijra act as signifiers for another secondary signification: that the transgender community is evil. Representations like these propagate the myth that the entire community is evil and dangerous.

Amrapurkar would not have adopted these exaggerations had the character been that of a heterosexual male. The fact that the character was a Hijra made it acceptable for its representation to caricaturise the transgender community. This is what makes the representation highly problematic. In the picture, Maharani’s character is juxtaposed with the relatively calm demeanour of the characters around her. This accentuates the frightening aspect. In the scene, she tells the protagonist Ravi (Sanjay Dutt), that he can spend the night with Pooja (a sex worker and Ravi’s love interest) if she is allowed to watch the sexual act. The character is shown to be not only evil, but also perverse and predatory.

The character representation plays on a lot of the existing stereotypes related to the transgender community which are resultant of the discourse surrounding the LGBTQ community. The mannerisms, sexual, predatory behaviour are the prominent stereotypes. The fact that Maharani is a brothel-owner who illegally buys young girls plays on the stereotype that most Hijras are criminals. In one of the scene, she says that since she is ‘half-male’ and ‘half-female’, and since she does not have beauty, the only thing she has is her brain. She thus, serves the males and sells the females. The scene plays on two main stereotypes. One being that the queer characters are cunning and evil. The other being that women are supposed to serve men.

In the scene, she tells the protagonist Ravi (Sanjay Dutt), that he can spend the night with Pooja (a sex worker and Ravi’s love interest) if she is allowed to watch the sexual act. The character is shown to be not only evil, but also perverse and predatory.

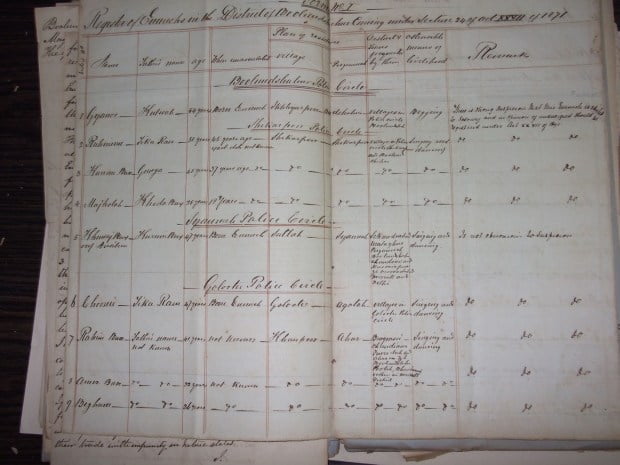

The stereotypes were a result of the practice of ‘othering’ against the transgender community which began during the British colonial era in India. The colonial police officials had maintained ‘registers of eunuchs’ (‘eunuchs’ was the British term for Hijras which the modern-day Hijras find derogatory). The registers were maintained for criminalised/marginalised communities. But, ‘registers of eunuchs’ had another purpose to serve; to monitor and eliminate Hijra households. This implicit motive was made explicit when Part II of the Criminal Tribes Act, 1871, targeted ‘eunuchs’ (primarily Hijras). The act said that ‘eunuchs’ who were ‘suspected’ of sodomy, castration and kidnapping should be registered with the police.

Hijras fell outside the binary of male-female endorsed by the colonisers, and thus, they were considered abnormal. By attributing the abnormality to their perceived sexual difference, the colonisers ‘naturalized’ the abnormality. In fact, India, before the colonial rule, had been open to multiple gender and sexual identities. Amy Bhatt, in an article titled, ‘India’s sodomy ban, now ruled illegal, was a British colonial legacy’, explains how sacred texts dating back to the Vedic ages tell stories of same-sex love and gender-morphing figures.

She cites examples of Shiva being worshipped as Ardhanarishvara, a multi-gendered figure composed of Shiva and his wife Parvati together, of texts showing hijras as a part of India’s political and social life, of Kama Sutra depicting a same-sex relationship and of homosexual depictions in temple sculptures. This was until the colonisers tried to fit people into their narrow binary of male-female.

Also read: A Critique Of Transgender Persons (Protection Of Rights) Bill, 2019

The colonisers contributed to a form of discourse which came to be called the ‘truth’ at a particular point in history. This discourse resulted in the representational technique of stereotyping. The stereotypes of criminal, predatory behaviour came to be associated with the queer community. The amplification of the difference between the queer and the heterosexual communities resulted in the stereotype of exaggerated mannerisms associated with the former.

In another movie, Tamanna, directed again by Bhatt, Paresh Rawal essays the role of Tikku who belongs to the hijra community. Many people believe that it is a positive step forward in the representation of the hijra community in cinema. Tikku adopts and takes care of Tamanna whom he had found abandoned as an infant. However, Tikku does not participate in the practices of his community, and has to hide his identity from his daughter. The secrecy maintained around the character’s identity is a pre-requisite to its dignified representation. Thus, if the movie takes a step forward, it takes two backwards. Not only Tamanna, films like Page 3, Traffic Signal, etc, misrepresent the hijra community.

The movie is made by a heterosexual male. He, in the most literal sense, has power over his subjects. The queer community, in Bollywood, is underrepresented, and thus, they are misrepresented. Queer characters are played by actors who may not identify as queer, and thus act according to their perception of the community. The entire community is reduced to a product of the actor’s perception of them.

The movie is made by a heterosexual male. He, in the most literal sense, has power over his subjects. The queer community, in Bollywood, is underrepresented, and thus, they are misrepresented. Queer characters are played by actors who may not identify as queer, and thus act according to their perception of the community. The entire community is reduced to a product of the actor’s perception of them. Films with queer characters are also helmed by directors who do not identify as queer. To be able to change the discourse (in this case the discourse of queer representation), one has to be a part of the discourse. Even though the maker of the film is in control of his subjects, he cannot escape being ‘subjected to’ the existing discourse.

However, not all is bad. The film industries in India are also taking a few positive steps in the direction of the LGBTQ representation in films. Faraz Arif Ansari, an independent filmmaker is not only credited with Sisak, India’s first short LGBTQ love story, but he has also since reached out to trans actors for the roles depicting trans people. Tamil cinema has opened up the space for trans actors with films like Naadodigal 2 and Peranbu.

Also read: (Mis)Representation Of Hijras In Popular Media

Super Deluxe has been momentous in terms of its representation of a trans woman (even though the character was essayed by a cis man). The film sensitively and realistically portrays the character, Shilpa’s, struggles with the gender-change surgery, her life as a trans woman, and her open and adorable bond with her son who is as accepting of her after the surgery as he was before. Therefore, we still await films that represent the hijra community realistically and respectfully, we cannot deny that a revolution has begun, and we have a long, long way to go.

Featured Image Source: Naukri Nama

About the author(s)

Simran is a masters student in Literature who never tires of exploring the interdisciplnary nature of Humanities.