Maha Laqa was the first female published Urdu poet of the Indian subcontinent. A courtesan by profession, she was a force to reckon with. She was adept at javelin throw and also had military calibre. She was also appointed as an ‘Omrah’, giving her the powers to advice to the king. A female voice in a male dominated darbar, she lived as an extremely influential and powerful persona of Hyderabad.

Life of Maha Laqa

Maha Laqa or ‘moon faced’ is the name given to a powerhouse of a woman, born as Chanda Bibi in 1768. Daughter of Raj Kunwar, a famous courtesan and Bahadur Khan, a military official of Bahadur Shah Zafar’s court, her story is one of success, honour, and grit.

Brought up by Mehtaab Ma, the childless sister of Raj Kunwar who was herself was an extremely sought-after consort in Hyderabad, Chanda Bibi had access to the court’s library, playing fields, and an exposure to court life from a very young age. The environment around her was fertile for growth and Chanda Bibi bloomed in the same. Being a courtesan’s daughter, she was free from the confines of home and ‘respectability’. Her ambiguous position gave space for her free spirit to prosper, giving her considerable agency on her body and work. We see this freedom in her growth and accomplishments. At a mere age of 14, she could throw masterful strokes at archery and learned horse-riding as well. These skills landed her in the military arena, as Mir Nizam Ali Khan took her along for three wars. She fought, donning a male attire and the strength of a woman.

Her sheer strength and strategy at these wars impressed the court, and she was conferred lands in multiple areas. Land has been an asset continuously denied to women. It stands as a marker of male privilege and patrilineality. Chanda Bibi’s possessions, therefore, were not just an individualistic endeavour. It was one of the many blows that patriarchy suffered at the hands of multiple women, buried in history. As an unmarried woman, she kept control of the lands and her asset throughout her life. Post her death, her assets were donated to the women of Hyderabad.

Land has been an asset continuously denied to women. It stands as a marker of male privilege and patrilineality. Chanda Bibi’s possessions, therefore were not just an individualistic endeavour.

A Powerful Courtesan

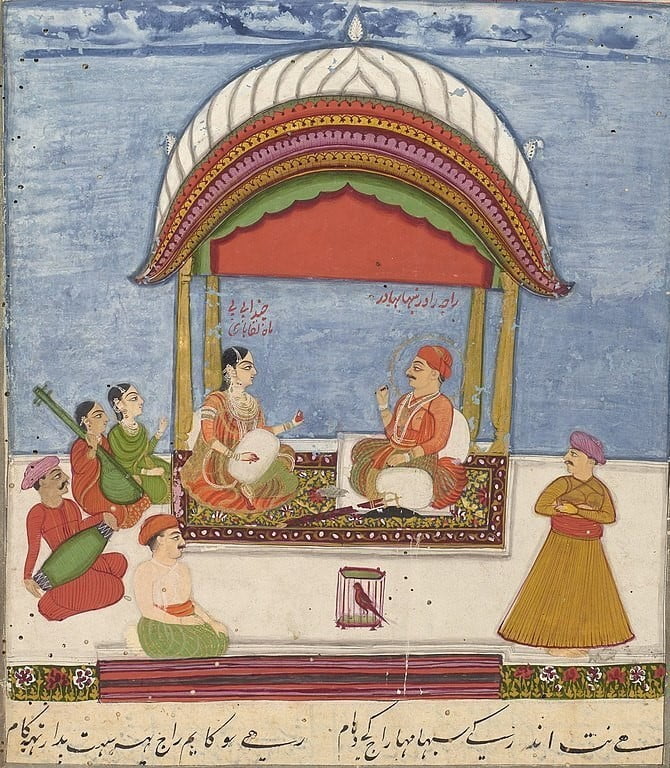

During her tenure, the Tawaaifs (courtesans) in Hyderabad also achieved an elevated position among other performers. As one of them got into the higher ranks of the court, the entire profession met with an upsurged status. This brings to light an important paradox: from a contemporary lens shaded with Victorian morality, Tawaaifs are viewed as objects without agency. They are considered as un-marriageable women whose birth marked their destiny and whose bodies were at the disposal of the courtly men. Chanda Bibi’s life inverts the same. Her position outside the confines of the home, gave her the chance of taking control in her hands. She was not obscured by a male patron, nor was she silenced by marital bounds. Instead, she reached high political ranks. So much was her influence that her entry in the darbar was announced by 500 foot soldiers and a drum composition.

Her position outside the confines of the home, gave her the chance of taking control in her hands. She was not obscured by a male patron, nor was she silenced by marital bounds.

The Artist

Along with a strong political calibre, Chanda Bibi was a celebrated poet and dancer. Proficient at Kathak, she was known to have an effortless gait in her movements. She was also known for her way with words, which is evident in her beautiful poetry. She wrote at a time, where mushairas or poetic gatherings were restricted to men. They were the writers and the conveyers of words. Women merely listened and marvelled or kept silence. Her poetry inverted the norms, and she became the only women to invade the male exclusive poetry scene of 18th century Hyderabad. Her ghazals were also anthologised in a diwan (a collection of Urdu poems) titled Gulzar-e-Mah Laqa, making her the first published female poet. She calligraphed all the 39 poems herself in this book. Thereby, claiming a stake in every nook and corner of her poetic endeavour.

Writing is not an artistic expression bereft of social context. It is documentation of history. It includes taking one’s stake in the process of authorship and narrativisation– a way of leaving a palatable mark. Indeed, Chanda Bibi left an indelible mark on 18th century history. Her writings on love, loyalty, and divinity inverted the patriarchal hold of romanticism. It gave her, a courtesan the power to write and claim love for herself and all the women around her.

References:

Featured Image Source: Wikipedia