The nexus between gender and leadership is contentious as it is, but even more so when the path to leadership in a workplace is a minefield of invisible obstructions. While the glass ceiling is slowly making its way into boardroom discussions, the precarious glass cliff is yet to receive the dire attention it needs. Glass cliff refers to the tendency of organisations to favour women and the other marginalised for leadership positions over men during a period of crisis and thereby putting them at a higher risk of failure.

The phenomenon, of course, is more prominent in higher-stake positions which are more susceptible to public accountability. Therefore, it can deter women and other marginalised persons and become an impediment to attaining representative leadership.

What Lies Beyond The Ceiling?

Coined by Michelle Ryan and Alexander Haslam, both psychology professors at the University of Exeter, the term “glass cliff” first figured in their 2005 research paper titled The Glass Cliff: Evidence that Women are Over‐Represented in Precarious Leadership Positions.

The study explores the difference in the experiences of women vis-a-vis men once they shatter the glass ceiling to take on leadership roles. The study examined the performance of the 100 companies on the London Stock Exchange during an all-time slump to see how it affected the suitability of men and women as leaders. It revealed that women were far more likely than men to be appointed as leaders in companies faring poorly.

Glass cliff refers to the tendency of organisations to favour women and the other marginalised for leadership positions over men during a period of crisis and thereby putting them at a higher risk of failure.

Thereby, the study on the concept concluded that more women than men were assigned overexposed leadership roles that warranted a magical turnaround in the organisation’s poor performance. It further exposed how the general perception erases this variability surrounding leadership tenure and exploits it to feed into the stereotypical adage of women as incompetent leaders.

What Drives One To The Edge Of The Cliff?

While this study pertained to examining company performance on triggering a glass cliff, another set of experiments conducted by the same researchers found triggers like gendered notions of leadership qualities, scarce vertical career growth opportunities, and the perceived stressfulness of the leadership position.

The 2008 study took responses from senior business members to attempt to understand the triggers that sustain the glass cliff and push women to the edge. The study found that women were perceived to possess ‘soft’ personnel skills and the ability for emotional labour owing to their gendered roles. This peculiarity made them more suitable than men for crisis-management.

Moreover, women were considered more suited to take on challenging leadership roles because they provided a rare ‘golden opportunity’ for career growth. However, the authors remarked that sexism, male in-group favouritism, and their need to avoid scrutiny might also push women to take up challenging glass cliff appointments. After all, the glass cliff culture runs on the inherent gendered assumption that women make no real contribution to a workplace and are, therefore, expendable.

Also read: 9 Indian Women in Combat Who Broke The Glass Ceiling

The Saviour Effect

The glass cliff also extends to racial and ethnic minorities, closely linked to another phenomenon known as the saviour effect. A research study was done on the transitions in America’s National Collegiate Athletic Association’s men’s basketball head coaches over 30 years.

Besides exposing racism and xenophobia, it found out that minority coaches were replaced by white men when they failed to deliver at a glass cliff appointment with a losing team. However, the study also observed that minority coaches/leaders never received the support and resources that their white counterparts did. Therefore, the study posited that the saviour effect results in a loss of confidence in minority leaders, and called it a parallel process of the glass cliff.

The discussions on the glass cliff in India range from glorifying the idea of a challenging leadership to misappropriating it as a self-defeatist attitude.

Where Does India Stand?

It may seem like a stretch to talk about the glass cliff when women in India are barely making past the glass ceiling to boardrooms at an appalling 13.8%. However, the glass cliff exposes the idea of representation in the workplace.

There is no evidence-based research on the glass cliff endemic to the different experiences in India. However, the little media-coverage that it has needs urgent addressing too. The discussions on the glass cliff in India range from glorifying the idea of a challenging leadership to misappropriating it as a self-defeatist attitude.

Glass cliff appointments indeed offer women and the other marginalised the best way to hold a leadership position. However, one must address the social and economic discrimination it perpetuates, and the workplace abuse it enables. Therefore, instead of rationalising the glass cliff and learning to manoeuvre one’s way around it, let us question the systemic issues that allow for it.

Also read: The Glass Escalator: Do Men Employed In Female Dominated Jobs Get Promoted Faster?

Research has shown that the glass cliff culture thins out in companies with a history of female leadership. Following that vein, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) had in 2018 mandated for all listed companies to have at least one independent female director on their boards. While this is a step in the right direction, corporations and regulatory authorities have to make concerted efforts to dismantle the glass cliff at the workplace and pave a road for women and the other marginalised to lead.

References

- Michelle K. Ryan and S. Alexander Haslam, The Glass Cliff: Evidence that Women are Over‐Represented in Precarious Leadership Positions (2005)

- Michelle K. Ryan and S. Alexander Haslam, The road to the glass cliff: Differences in the perceived suitability of men and women for leadership positions in succeeding and failing organizations (2008)

- Alison Cook and Christy Glass, Glass Cliffs and Organizational Saviors: Barriers to Minority Leadership in Work Organizations? (2013)

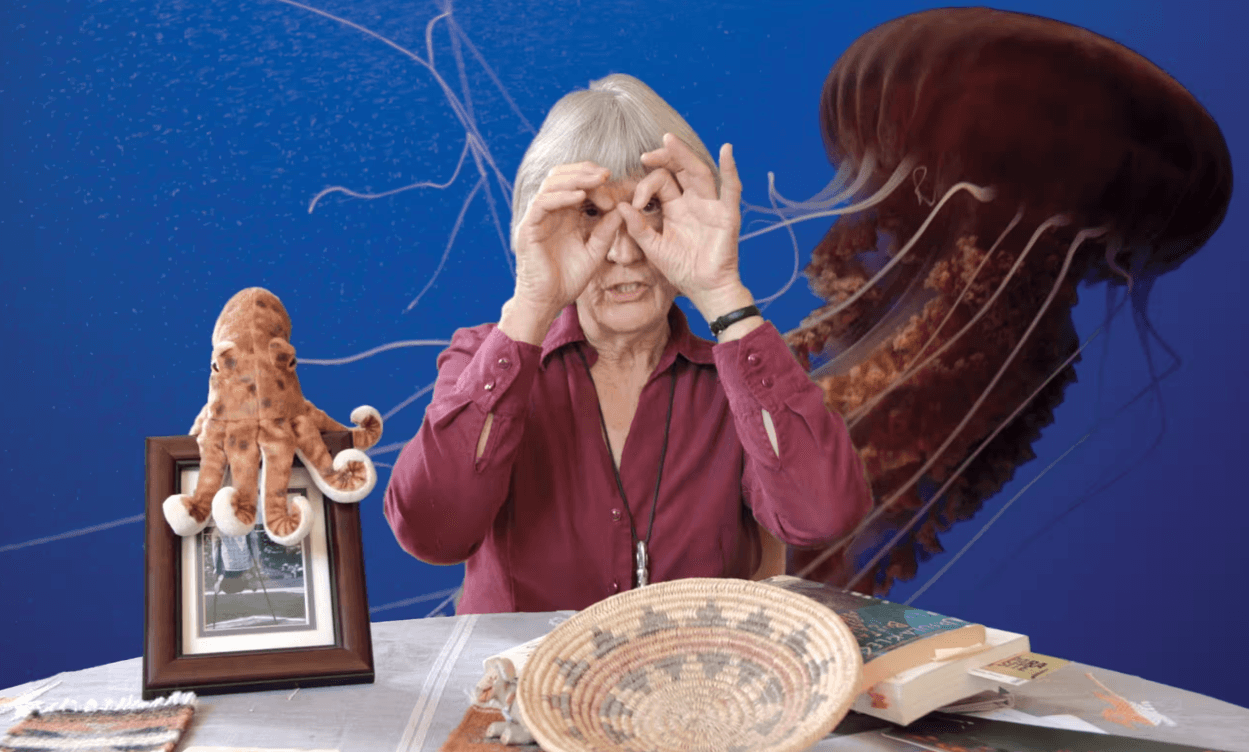

Featured Image Source: LinkedIn